Two-War Antifascists: Black American Volunteers Take Stock of the Jim Crow Military During World War II

The African American veterans of the Lincoln Brigade who joined the US armed forces during World War II were demoralized and embittered by the gross inequalities and color lines they experienced daily. The purported stakes of World War II—crushing fascism and saving democracy—intensified their outrage, which turned into militancy.

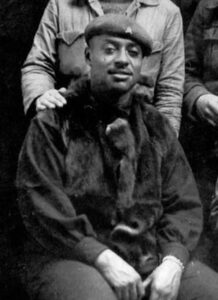

James “Bunny” Rucker enlisted in the 92nd Infantry Division of the U.S. Army in 1942 because he wanted to kill fascists. It was as simple as that. “I took personal pride in that I acted on the basis of my hatred against Hitlerism at all times,” he later explained, “and I had personal hopes that I’d be given by my own country even a limited opportunity to express that hatred through some measure of participation in our armed forces.” He understood that the front lines were in Europe. But as a militant Black antifascist, he refused to distinguish between the urgency to destroy fascism on the battlefield and the need to do so at home. He believed in his bones that the struggle would not be complete until it had achieved “full equality for Negroes in all phases of American life without compromise.”

Like many Black soldiers in the Jim Crow military, however, Rucker’s hopes were quickly dashed. He joined the ranks of an army mobilized in total war against fascism, only to spend mindless months toiling on labor detail in North Carolina: collecting trash, hauling scrap metal, and trimming shrubbery. “This is narcotic,” he wrote to his wife in desperation. “I’m losing touch with the struggles that my uniform represents, and that hurts.” Like countless other Black servicemen and women, war workers, and Black Americans more generally, Rucker was demoralized and embittered by the gross inequalities and color lines that cut across the armed forces and defense industries. Although the system operated in parallel to the barriers and degradations of civilian life, the purported stakes of World War II—a great global showdown to crush fascism and save democracy—intensified his outrage. In the face of such American hypocrisy, Rucker and other Black soldiers found themselves radicalizing as their indignity spilled over into militancy. On the home front, this experience coursed across the Black public sphere, embodied most famously in the popular antifascism of Pittsburgh Courier’s “Double V” campaign, which insisted that the fight against fascism must take place “over there” and at home.

In many respects, Rucker’s despair and frustration, as well as his understanding of fascism and Jim Crow as twin enemies, were commonplace in wartime Black America. Still, he was among a small cohort of soldiers uniquely poised to rage against Jim Crow in uniform and find the idea of a segregated mobilization against fascist forces absurd. Rucker did not simply crave combat; he wanted to return to it. Pulling weeds at Fort Bragg was especially insulting to someone seasoned in armed antifascist struggle, who knew the wail of Nazi bombers, whose white superior officers readily admitted he had more experience and knowledge than they did. Like countless other disgruntled and battle-hungry Black soldiers, Rucker’s understanding of what fascism was, and how to fight it, was rooted in his coming-of-age in Jim Crow America. Unlike most of his comrades-in-arms, however, he was a veteran of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.

As readers of this magazine will know, at least 83 Black Americans were among the roughly 2,800 volunteers from the United States who joined the International Brigades in Spain. Rucker, a communist from Roanoke, Virginia, who lived in Columbus, Ohio, sailed for Spain via France on the President Roosevelt in February 1937. As Robin D. G. Kelley, Cedric Robinson, and others have noted, many Black volunteers were drawn to the struggle of Republican Spain in 1936 through the surge of antifascist militancy and grassroots solidarities fueled by Fascist Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia the year before. In making this connection, scholars have elevated Black perspectives, making clear not only that the fight against fascism extended beyond Europe, but that fascism itself was understood as a racist and imperialist project. Still, few scholars have looked to the handful of Black Americans who returned from Spain and then, in a few years’ time, found themselves as soldiers back in Europe.

Black antifascists like Rucker initially grappled with fascism’s familiar contours—its racial-imperial grammar—between Scottsboro and Addis Ababa; then amidst blood and dust in the Ebro Offensive; then in basic training in the Deep South, followed by the segregated ranks of the U.S. armed forces as they pushed their way northward into Italy and across the wrecked expanse of the western front into the Third Reich. What perspective did a seasoned antifascist soldier like Rucker bring when he finally volunteered for the front and returned to Europe to fight in Italy in July 1944? How did his antifascism differ from that of U.S. War Department propaganda and the more tempered strains of patriotic antifascism printed daily under the banner of “Double V”?

Letters written by Black antifascists like Rucker who saw combat in both Spain and during World War II make clear that, throughout, they held on to their earlier understanding of what it meant to defend democracy by fighting fascism and racism head-on. As two-war antifascists, they were better positioned to understand the war as but the latest front in a larger struggle to destroy fascism in all its forms—and to cultivate a world where its permutations and afterlives wouldn’t stand a chance.

This view certainly put them at odds with the mainstream. As we know, the Second World War generated a remarkable, though fleeting, moment in U.S. political and popular culture in which limited strains of antifascism became not only acceptable but seen as outright patriotic. In contrast, the voices of two-war antifascists like Rucker demanded a more radical reflection. What was at stake was not only the nature of the war and what it should mean to Black Americans, but, more broadly, the relationship between democracy and fascism once the war was won. Historians have long argued for the role played by Black soldiers and other veterans to the Black freedom struggle before, during, and after World War II. But the perspectives of this small cohort of Black volunteers in Spain who went on to fight in the Jim Crow Army in Europe remind us to situate their “martial freedom movement” in antifascist terms—as something far more visionary than official U.S. policy.

Another one of these two-war antifascists was Bert Jackson, a Black artist from New Jersey who had joined the CP in 1935 and sailed for Spain in May 1937 and returned in December 1938. In February 1942, he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps. As he wrote soon after, despite the new uniform, he held fast to the idea that he was still, or perhaps once again, “a member of a fighting anti-fascist Army.” Jackson meant that his aims remained the same as they had been five years earlier. His vision of democracy—a democracy not yet realized in the United States—was inherently antifascist. More importantly, democracy was not to be taken for granted, nor was it a given that it would flourish from the postwar rubble, like some force rushing back into the crater left by Nazi Germany’s surrender. For Jackson, the fight for democracy, and democracy itself, must necessarily be an antifascist project. It was a subtle but important distinction.

Jackson’s friend Walter Garland, a Black musician from Brooklyn who served in Spain and enlisted in the Army in 1942, took a similar position to his comrade. Early in the line of duty, Garland wrote that he found the U.S. Army was falling short in developing its men into “the mighty anti-fascist force needed” to beat fascism once and for all. Of course, he observed, the military’s pervasive culture of white supremacy and attendant low Black troop morale were the main reasons for this shortcoming.

Bunny Rucker’s letters home indicate he would have wholeheartedly agreed. Early in his service, he was transferred to “non-combatant limited service”; like many Black GIs, he was denied a combat role. In a letter to his wife, he grieved this “truly foul blow.” “Even my own commanders recognized the insult,” he remarked, given his ample combat experience in Spain. Strategically speaking, he pointed out, the fact that both military leadership and the federal government remained so committed to the inefficiencies of Jim Crow “in the midst of a life and death war with the most ruthless, most destructive enemies of mankind in all the history of the world,” suggested a sinister disregard for actual antifascist struggle—and for the freedom and justice antifascism promised in the wake of victory. In Spain, Rucker had served in a “people’s army.” By contrast, what he suffered while wearing an American uniform amounted to “chain-gang, concentration camp measures of oppression, which is national minority oppression carried to a high degree and the Jim Crow Army has nothing whatsoever in common with a democratic Army of national liberation” [1]

While Rucker wrote of his own struggles with the Army’s color lines, he also warned of their extension back to U.S. soil—clear evidence, from where he stood, of Jim Crow’s close kinship with fascism. For Rucker, the army’s commitment to the Jim Crow status quo prevented the United States from ever reaching its purported war aims. In his correspondence he pressed further, warning that the country’s overt and latent fascist sympathies meant it would never land on the right side of the antifascist struggle.

Despite everything, men like Rucker, Jackson, and Garland found pride in returning to combat and once again facing off against a fascist foe. Rucker stood strong. He garnered recognition from select white superiors, while his combat experience eventually earned him a heavy weapons post, which surpassed that of his Commanding Officer. Meanwhile, although Bert Jackson’s antifascist fighting spirit suffered gravely while stationed in Alabama, he too remained eager for combat, linking his suffering under Jim Crow to the suffering the fascists caused the world. He longed, he wrote, for “a chance at the major perpetuators of racial superiority,” and considered himself the ideal antifascist agent to take on the Nazis. “And think how ‘der fuehrer’ will feel,” he wrote, “when he sees his prized air force knocked out of the sky by people he has taught his ‘Aryans’ to despise.”

Although these men took far more critical perspectives on Black military service and the hypocrisy of U.S. ideals in the war effort, they nonetheless recognized the urgency of the historical moment and the significance of having Black soldiers at the helm in crushing the Axis. In a way, their positions straddled the conditional wartime patriotism embodied in the “Double V” campaign and the vision of Black radicals like W.E.B. Du Bois, Claudia Jones, and C.L.R. James, who interpreted the war as a racial-imperial catastrophe unfolding on both sides, even as they recognized the short-term need for an Allied victory.

In framing democracy as inherently antifascist, this cohort of two-war antifascists showed remarkable resolve and prescience about the problems of peace, captured well by Du Bois in May 1945, when he wrote: “We have conquered Germany but not their ideas.” Their correspondence in combat shows exceptional concern over the risks of abandoning the struggle against fascism on the battlefields of Europe, even as the dust settled, and the grind of tanks came to a stop. In the midst of the war, they warned against ceasing the fight for democracy at home after it had purportedly been secured in Europe.

In the final months of the war, Bunny Rucker fixated on what he viewed as a bleak future despite the impending realities of peace. Reporting from combat in Italy in January 1945, he was focused on battles to come. Jim Crow, he insisted, was the opposite of democracy. In fact, “Jim Crow is fascism and fascism is death.” That April, the end of fighting in sight, as Rucker was wounded and faced a long recovery, his morale collapsed despite the positive reports from abroad. News of peace in Europe and later in the Pacific came to him in a hospital bed, where he fell into despondence over the false promises of the war’s end. “I’m very disgusted with the whole Goddamned mess,” he confessed in a letter in October 1945. “The hospital, the Army, the Government, the country and the people in it.”

His frustrations over his long and fitful recovery paled in comparison to the disaffection he felt for his country and his disillusionment with its capacity for change. On the U.S. role in denazification and democratization in Germany, he wrote: “there is such a small part of American life that has any more integrity than there was in Germany.” To Rucker, in other words, the antifascist struggle was far from over. “The purpose of the war sacrifices was to make living tolerable,” he remarked: tolerable for the racialized and colonized, for the subjugated and oppressed, for the workers and toilers all the world over. To be sure, many Black servicemen and women suffered similar disappointment and trauma in the wake of the war. But in light of the longer march of Rucker’s antifascist militancy, his frustration hangs especially heavy.

The postwar activism and militancy of Rucker, Garland, Jackson, and their comrades show that they kept up with the struggle to destroy fascism: this time on U.S. soil. And while postwar politics may have kept them from framing their ongoing activism in antifascist terms, their antifascism did not end in 1945, just as it did not start in 1941. Their legacies compel us to unshackle histories of U.S. antifascism from the narrow, triumphalist window of the World War II era, and place them instead in the long arc of the Black antifascist tradition.

Anna Duensing is a historian specializing in African American history, Black radicalism, transnational social movements, and the evolving global politics of white supremacy. She teaches at Villanova University, where she is a Faculty Affiliate of the Albert Lepage Center for History in the Public Interest.

[1] Bernard “Bunny” Rucker to Helen Rucker, November 18, 1943; James Bernard Rucker Papers; ALBA.212; Box 1; Folder 3; Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives Elmer Holmes Bobst Library.