As McCarthyism Returns, New York Remembers the Hollywood Blacklist

Seven of the Hollywood Ten, 1950. Shown from left: Samuel Ornitz, Ring Lardner Jr., Albert Maltz, Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Herbert Bieberman, Edward Dmytryk. Courtesy of Photofest

As the government’s attempts to control and punish US universities and the media are conjuring up memories of McCarthyism, the New York Historical is hosting an exhibit, on view until October 19, that revisits the time when the House Un-American Activities Committee took aim at the entertainment industry.

“Blacklisted: An American Story,” conceived in 2015 by Ellie Gettinger, then curator of the Jewish Museum in Milwaukee, was first shown there in late 2018 and has since been traveling the country. Objects on display include touching letters to and from Alvah Bessie, the only Lincoln vet among the Hollywood Ten, and Ring Lardner, Jr., also among the ten individuals sentenced for contempt of Congress in 1947. (Lardner’s younger brother James died in Spain.) The show aims to “prompt visitors to think deeply about democracy and their role in it,” said Louise Mirrer, president of the New York Historical. “The exhibition tackles fundamental issues like freedom of speech, religion, and association, inviting reflection on how our past informs today’s cultural and political climate.”

Although the New York Historical uses a lot of the material from the original exhibit—Wisconsin, in addition to being Joe McCarthy’s home state, also houses the archives of more than half of the Hollywood Ten—it has updated and expanded Ettinger’s original design. The first section of the installation, for example, covers the three decades preceding HUAC’s focus on Hollywood at the beginning of the Cold War, from the first Red Scare in the 1910s to the Great Depression. In the 1930s, the entertainment industry got involved in the fight for social justice, against racial segregation, and against the rise of fascism—causes in which the CPUSA, which had been founded in 1919, played a central role. A 1932 lithograph on view depicts the CP’s interracial presidential ticket of William Z. Foster and James W. Ford, the first African American to run for vice president in the 20th century, which reads: “Equal Rights for Negroes Everywhere! Vote Communist.” “We decided to make more space for this part of the story because we wanted to make sure that HUAC did not get to define for us, or for our viewers, what role the CPUSA played in the 1930s and ’40s,” Anne Lessy, assistant curator of history exhibitions and academic engagement, explained in an interview.

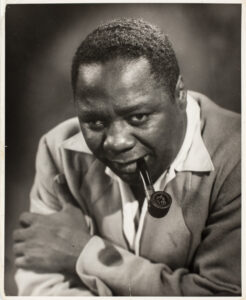

Other additions to the original exhibit include a painting by Lincoln vet Ralph Fasanella, “McCarthy Press,” from 1958, on loan from the American Folk Art Museum, and a US map showing all the locations where HUAC held hearings over the close to four decades from its founding in 1938 to its abolition in 1975. Panels listing the Hollywood individuals who were obligated to work anonymously, forced into exile, or died prematurely (including John Garfield and Canada Lee) showcase the impact the congressional investigations had on the livelihoods, and often lives, of the more than three hundred individuals from the entertainment industry who found themselves on a blacklist somewhere. “Although some of those blacklisted were able to work again under their own name in the early 1960s, it’s hard to exaggerate the long-term chilling effect HUAC had on the place of activism in the entertainment industry and the political culture of this country more generally,” Lessy said.

Editta Sherman (1912-2013), Canada Lee, undated. Gelatin silver print. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical, Gift of Kenneth Sherman.

The show closes with a look at the New York theater world, which tells a different story. While the Hollywood unions eventually gave in to political pressure, the New York actors’ unions did not. Instead, they defied HUAC both on and off Broadway. In 1952, for example, at the height of the Red Scare, Lillian Hellman—who had been blacklisted in Hollywood—would direct a revival of her own 1934 play, The Children’s Hour.

To illustrate the kind of suspicions that the second Red Scare stirred up, a display reprints a page from the section dedicated to Langston Hughes in Red Channels (1950), a booklet that claimed to expose more than 150 writers, musicians, broadcast journalists, and others as subversives. Among the evidence listed for Hughes is a poem, “Goodbye Christ,” written in 1932, which the pamphlet claims is a “typical example” of the “vicious and blasphemous propaganda Communists use against religion.”

The exhibit includes several viewing stations with clips from movies whose political content was considered suspect by HUAC and the FBI. These include films like A Gentleman’s Agreement (1947), with John Garfield and Gregory Peck, which puts the spotlight on the persistence of antisemitism in postwar US society. John Garfield’s FBI file, which runs more than 1,100 pages, claims that the film “followed the Communist Party line in that it caused racial agitation which otherwise might not come about unless portrayed in a film of this sort”. “For HUAC and the FBI, the fact that injustices were openly addressed was often considered more of a problem than those injustices themselves,” Lessy said.

ALBA Board member Sebastiaan Faber teaches at Oberlin College.