From Brick and Mortar to Robert Capa’s Silver Crystals–and Back Again

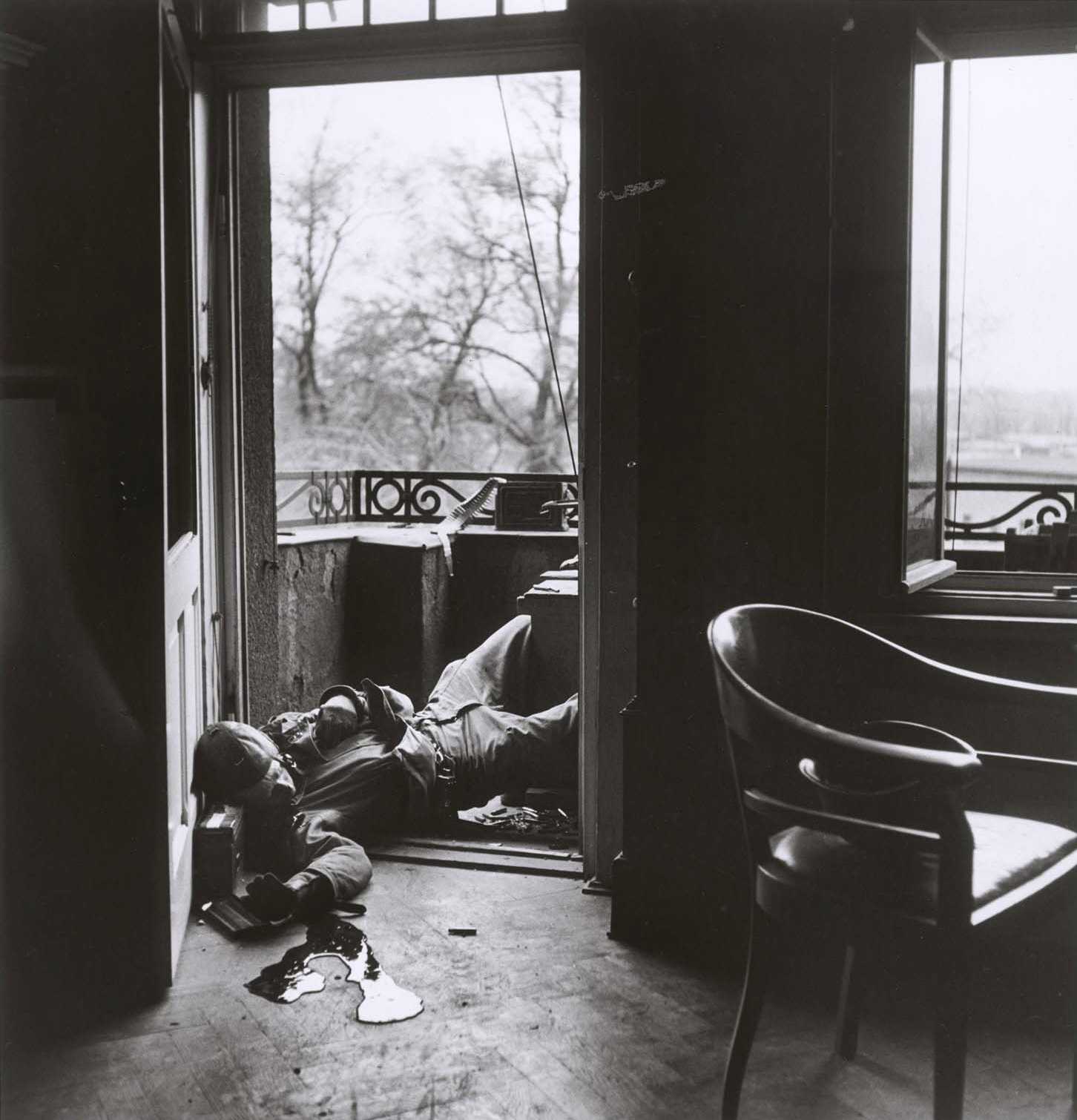

Robert Capa, [American soldier Raymond Bowman killed by a German sniper, Leipzig, Germany], April 18, 1945. ICP/Magnum

In recent years, citizen groups in Leipzig and Madrid have fought to preserve the buildings that were backdrops in two of Robert Capa’s best-known photographs. Their steadfast dedication has created two sites of historical memory whose significance extends far beyond Capa’s original images.

Leipzig

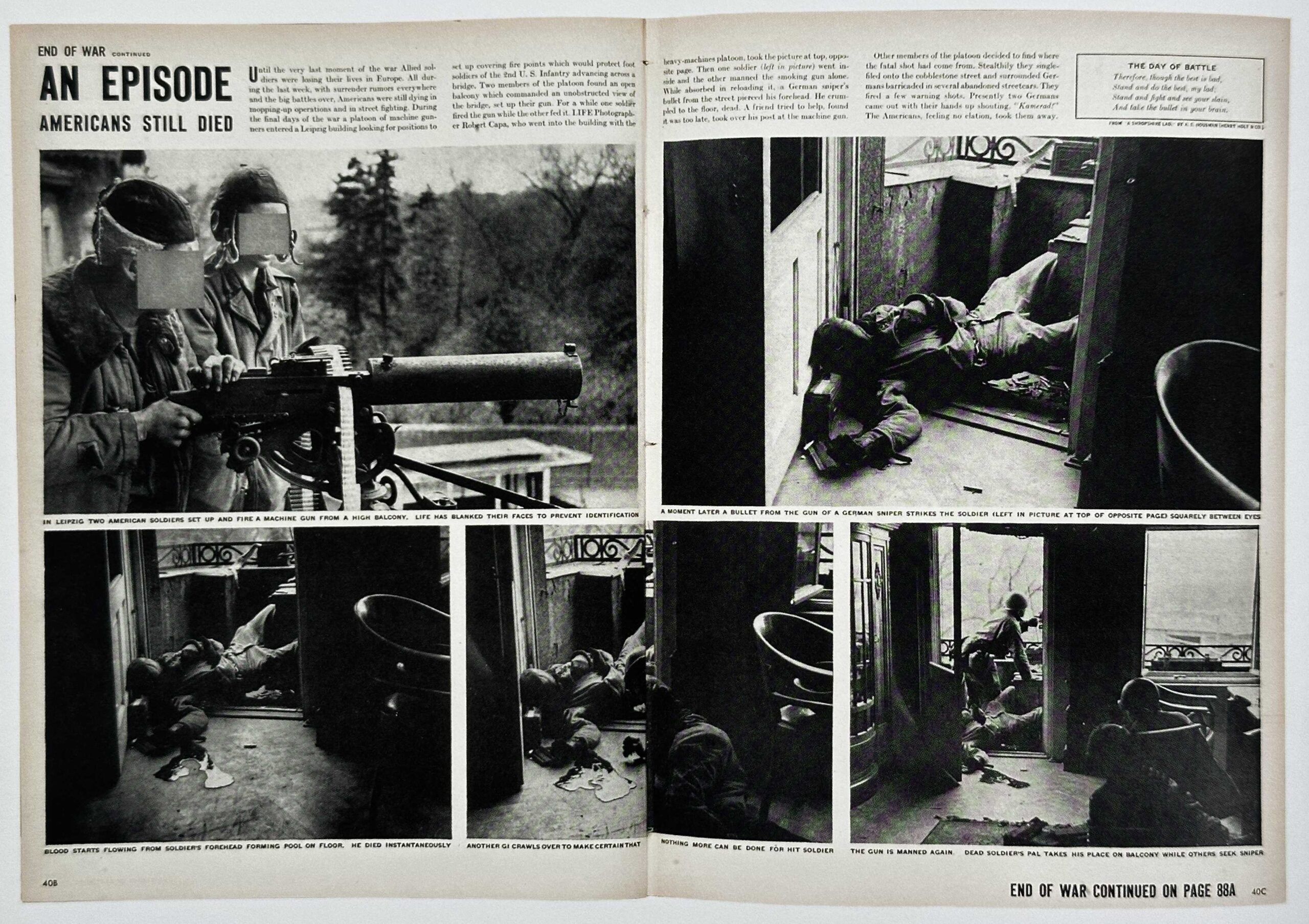

On April 18, 1945, as the Allied troops were liberating the city from the remaining German soldiers, Capa photographed American soldiers shooting out a balcony of an apartment just outside the city center, including the death of a soldier killed by a German sniper. The sequence was first published in Life magazine. Shot only weeks before the end of the war, the soldier became for Capa his metaphorical “last man to die” in World War II.

The Leipzig building suffered neglect over the years. Covered in graffiti, it was slated for demolition in 2011. Because the story of the American liberation was rarely acknowledged in the GDR, the image did not circulate widely. Still, Mike Hoffmann, a political cabaret artist, had seen the Capa image published in a banned underground magazine in the 1990s and he was determined to locate the site. In 2012, he finally identified the derelict building on Jahnallee 61. Next, Ulf-Dietrich Braumann connected on social media with Lehman Riggs, the 82-year-old American soldier who had been on the balcony when his buddy was killed. Although Riggs remembered his name as Robert Bowman, the historian Jürgen Möller soon discovered it was Raymond Bowman.

In the years following, a group of activists, scientists, and historians campaigned to encourage an investor to help renovate the historic building and dedicate a ground-floor space to an exhibition about Bowman, Capa, and the Allied campaign during WWII. They even contacted the children of the family who lived in the apartment during the war, who gave a desk and chair from the original room, which are now on display.

The Capa Haus space, which opened in 2016, hosts an annual event every April to coincide with the anniversary of the Capa photograph. They were able to bring Riggs to Leipzig and witness the renaming of the two streets crossing in front of the building: Bowmanstrasse and Capastrasse. American and German politicians have spoken at their gatherings, along with German labor camp survivors, American veterans, and post-conflict peace mediators. Given the poignancy of the annual event, it’s no wonder it has become a fixture of the Leipzig cultural calendar.

Madrid

Calle Peironcely number 10 is a one-story structure in the heart of the Puente de Vallecas district, a working-class neighborhood in the south of Madrid. In November 1936, five months after the start of the Spanish war, Capa made several photographs of children playing outside this bullet-pocked building. At the time, these images appeared in newspapers and magazines around the world, from China to the US and across Europe. In 1938, Capa selected one of them for his book about the war, Death in the Making.

Robert Capa, [Three children outside bullet-riddled building following an air raid, 10 Peironcely Street, Madrid], November-December 1936. ICP/Magnum

What distinguished the Spanish Civil War from previous armed conflicts was the frequent use of bomber planes, flown by German and Italian pilots, that indiscriminately targeted cities and civilians. Hundreds of buildings were ruined or crushed beyond recognition or reconstruction. On that day in November, Capa was out photographing the aftermath of one of the bombings. As he roamed the city, he found these three children sitting in the sun. In the photograph, they seem to be playing as children do, free from the scrutiny of terrorized adults. Capa must have been drawn in by the incongruity between the lightness of the children and the scarring marks of history on the wall behind them. His photograph forces us to consider how the violence of war affects the lives of civilians—an obvious fact now, but more novel in 1936. It is an image of resistance.

Capa’s reputation has only grown since his sudden death in 1954, at age 40. Because Capa is by now considered as one of the greatest photographers to cover the Spanish battle against fascism, his images have become deeply intertwined with the collective memory of the war. Over the past few decades, fascinated local historians and photo enthusiasts have tried to find the exact location of many of his Spanish images. In some cases, large-scale reproductions of his work have been installed in the place of the original photograph.

It was the photographer José Latova who, in 1998, recognized the building in Calle Peironcely while going through a collection of Madrid municipal photographs. In 2010, a group of concerned citizens who call themselves #SalvaPeironcely10 designed a master plan to memorialize the complex history of the building. They proposed to use the building as an educational center with exhibitions, classes for children and adults, events, and a research area for information related to the war, photography, and housing as seen through the lens and catalyst of the Capa photograph.

At the time, the structure, which dated from 1927, housed 14 families in a warren of small windowless rooms, some of which were just over 180 square feet. The white plaster walls were damp and frigid throughout the winter months and boiling in the summer, there was exposed wiring, and insects and rodents thrived. It was one of the only prewar buildings remaining in a neighborhood of postwar construction. The owner, who was planning to tear it down, had crudely replastered some of the bullet marks on the front wall in an attempt to cover up the historical war damage.

In the years following, the residents worked closely with the group formed to save the building. They held numerous public meetings to educate people about the Capa photograph, the history of the war, and their housing rights. This multi-faceted story, told by a diverse coalition of residents, artists, professors, and foundations, gained such traction that in 2017, while the city government was in progressive hands, the building was recognized as a protected city landmark, preventing the owner from going through with any redevelopment plans.

Former director of the National Library of Spain, Rosa Regàs, speaks at the event Night of Tales in the Outskirts of Memory, held on June 9, 2018, in front of the building immortalized by Robert Capa. Photo: Nacho Rubiera

When I first visited the site in the fall of 2019, there had been interventions with children from neighboring schools in the open field across the street to teach them about the war and local history and to make a colorful mural based on Capa’s photograph. The “Robert Capa Was Here” Festival that year collaborated with the Museo Reina Sofía to hang the Capa photograph in a room near Picasso’s Guernica. Archeologists made preliminary excavations of the area and found artifacts from the war and an old terracotta flooring.

In 2021, the Madrid City Council expropriated the building and provided new housing for the residents. While this was a positive step for the residents, the city government, which by then had turned conservative, did not move forward on the plans for a cultural center. The campaign to have the building designated as a Robert Capa Center for the Interpretation of the Aerial Bombings of Madrid, as originally proposed, stalled.

As of the summer of 2025, the Directorate General for Democratic Memory has initiated the procedure to declare the site a Place of Memory, and Peironcely 10 will receive protection from the Spanish Government. This will hopefully put pressure on the city council to recommit to their engagement with the site and the proposed cultural project. By preserving the building and building education around its history, they are doing more than just preserving a physical structure. They are preserving a history of the inhabitants, a history of the city, of a war, and of photography.

***

The German and Spanish projects inspired by Capa’s photographs are a testament to the power of citizen action to shed light on past histories that have been intentionally obscured for political gain. They are also a tangible reminder that photographs matter. On Peironcely and Bowmanstrasse, Capa’s photographs, ephemeral as all photographs are, have found a material permanence in brick and mortar. Photographs—whether they are silver crystals on paper or digital information on a screen—hold deep reserves of history for all of us to mine.

Cynthia Young, an ALBA board member, is a curator based in NYC and worked for many years as the curator of the Robert Capa Collection at the International Center of Photography.