“Fascism Was Ben Shahn’s Greatest Fear”–Laura Katzman on the Timeliness of Antifascist Art

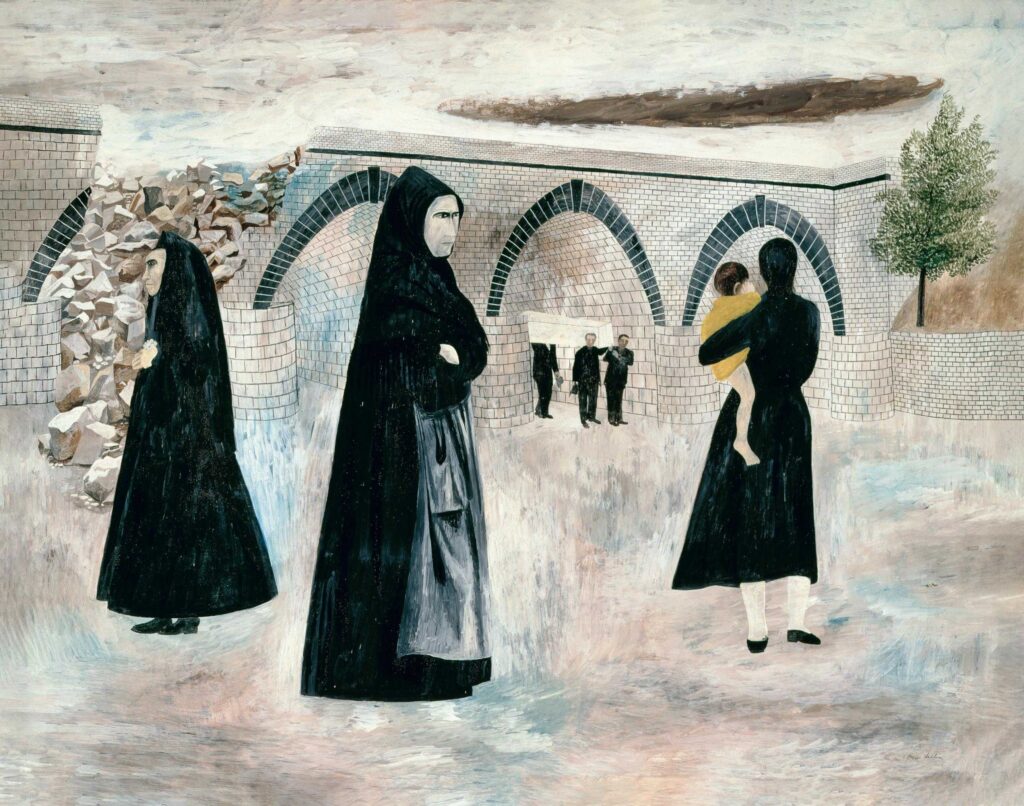

Ben Shahn, Liberation, 1945, gouache on board, 29 ¾ x 40 in. (75.6 x 101.4 cm.) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. James Thrall Soby Bequest, 1980. © 2025 Estate of Ben Shahn / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

The Jewish Museum in New York City is presenting the first U.S. retrospective in nearly half a century dedicated to social realist artist and activist Ben Shahn (1898-1969). Curator Laura Katzman reflects on Shahn’s social justice work as it relates to the antifascist struggles of his day.

Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity examines the progressive artist’s commitment to confronting crucial issues of his era, spanning from the Great Depression to the height of the Vietnam War, as well as to exploring spirituality and Jewish texts. Featuring 175 artworks and objects from the 1930s to the 1960s, the retrospective highlights the enduring relevance of Shahn’s art and the complexity of his layered aesthetic as he shifted from documentary to allegorical and poetic styles in pursuit of a visual language that would resonate widely. On view through October 26, 2025, the exhibition is organized by Dr. Laura Katzman, guest curator and professor at James Madison University, in collaboration with Dr. Stephen Brown, Jewish Museum curator. It is adapted from the acclaimed retrospective curated by Dr. Katzman for the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid (2023-24). I spoke with her in August.

How does the Spanish Civil War figure in the life and work of Ben Shahn?

Like many left-wing artists in New York from working-class, Jewish immigrant backgrounds, Shahn joined Popular Front coalitions in the 1930s. He fervently tracked the Spanish Civil War and supported the Republican cause. While Shahn was not among the estimated 2,800 Americans who fought in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, as an artist of Jewish heritage he understood what was at stake in Spain, the country of the Inquisition. As we know, Jewish activists were in fact overrepresented in the International Brigades.

Shahn likely shared the socialist, anti-Stalinist perspective that George Orwell adopted in Homage to Catalonia (1938) and undoubtedly read André Malraux’s L’Espoir (1937)—a despairing political novel about the war’s tragedy as a symbol of the human condition. He worked closely during the Great Depression and World War II with poet-activists Muriel Rukeyser and Archibald MacLeish. Rukeyser’s poem Mediterranean (1937) and MacLeish’s co-written scenario for the film The Spanish Earth (Joris Ivens, 1937) circulated in Shahn’s orbit. In the summer of 1935, Shahn joined the committee that rewrote the “Call” for the first American Artists’ Congress against War and Fascism, which he signed. He was an early editor and designer of Art Front, organ of the Artists’ Union, which published articles on Spanish artist Luis Quintanilla, whose imprisonment due to his role in the October 1934 Revolution mobilized aid from the global intellectual community. In fact, Shahn photographed Artists’ Union members marching at the Spanish Consulate in New York City in the spring of 1935, carrying signs declaring, “Free Quintanilla and Other Victims of Spanish Fascism.” The pictures show U.S. left-wing solidarity with Quintanilla and his colleagues, who opposed the entry of right-wing forces into the Spanish Republican government.

Shahn’s close friend and assistant on the ill-fated Riker’s Island mural (1934-35), Joe Vogel, fought in the International Brigades. As late as 1963, Shahn participated in an exhibition in support of a campaign by the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade to free imprisoned Republicans in Franco’s Spain. In Shahn’s last interview in 1969, he suggested that the United States and Western allied powers should have militarily aided Republican forces to defeat the Nationalists. Most poignantly, close to his death on March 14, 1969, Shahn created in Puerto Rico what were likely his last drawings: life-sketches of Pau (Pablo) Casals, the world-renowned Catalan and Puerto Rican cellist, who was an impassioned supporter of the Spanish Republic and his fellow exiles.

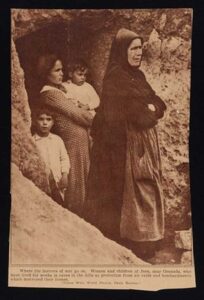

Throughout his career, Shahn amassed an extensive archive of photographic images, many of which he creatively adapted in his paintings. In Italian Landscape, created during World War II, he employed images of Spanish Civil War refugees that he had clipped from newspapers, to represent the destruction wrought in Italy by fascism. For Shahn, the two conflicts were battles in the same war.

Throughout his career, Shahn amassed an extensive archive of photographic images, many of which he creatively adapted in his paintings. In Italian Landscape, created during World War II, he employed images of Spanish Civil War refugees that he had clipped from newspapers, to represent the destruction wrought in Italy by fascism. For Shahn, the two conflicts were battles in the same war.

Painting: Ben Shahn, Italian Landscape, 1943-44, tempera on paper, 69.8 x 91.4 cm. Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Gift of the T. B. Walker Foundation, Gilbert M. Walker Fund, 1944. © 2025 Estate of Ben Shahn / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Photograph: Times Wide World Photos, Paris Bureau, “Where the Horrors of War Go On. Women and Children of Jaen, near Granada…Air Raids and Bombardments Which Destroyed Their Homes,” c. 1936-37, newspaper clipping, 21.6 x 14 cm. Ben Shahn papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

How did it feel to see Ben Shahn’s work exhibited in the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid?

It was incredibly moving to present the Shahn exhibition in the Reina Sofía, one floor below Picasso’s Guernica (1937), arguably the most riveting visual condemnation of the atrocities that crushed the fragile, young Spanish Republic. To Shahn, Picasso was a “monument”; he admired Guernica as a “passionate testament [of the artist’s] sympathies” and a symbol of artistic nonconformity. Yet in a landmark conference on Guernica held at the Museum of Modern Art in 1947, he also publicly critiqued the semi-abstract painting because he thought it did not speak to the layperson. The Reina Sofía, a former hospital, is equally important as a repository of historical memory because it was targeted by Nationalist bombings during the war.

Curating Shahn’s first solo retrospective exhibition in Europe since 1963 compelled me to look at Shahn through a new lens. The Shahn show in Madrid was a brainchild of then-director Manuel Borja-Villel. Its immensely positive reception—it was an unexpected blockbuster—underscored the power of Shahn’s antifascist work. The Spanish and global audiences who flocked to the exhibition recognized the timeliness of Shahn at a moment when many European democracies, including Spain, are threatened by the rise of far-right political parties. They also acknowledged the exhibition as a kind of “homecoming” for Shahn. Shahn’s “return” to a democratic Spain is of course symbolic, because like many international supporters of the Republic, he avoided travel to Franco’s Spain.

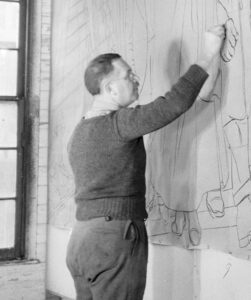

Arthur Rothstein, Untitled (Mural Painted by Ben Shahn at the Community Building, Hightstown, New Jersey), May 1938, 4 x 5 inch negative or smaller. FSA/OWI Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

“The Jewish Museum has mounted a vital exhibition called Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity, showing why authoritarians are so often afraid of artists who use their canvases to speak against social and political injustice … By resisting outside pressure, artists like Shahn … have demonstrated what resistance to an authoritarian culture looks like. But can only private institutions let artists speak their minds? For most of its existence, the Smithsonian largely presented a polished, authorized version of cultural history; only in recent years did a new generation of historians and curators allow contrasting views to emerge. As Shahn knew, art can only be effective at illuminating and healing if it is unconstrained by authority.” —David Firestone, New York Times, April 8, 2025

What was the role of antifascism in Ben Shahn’s life and work?

Antifascism and anti-authoritarianism are key themes in Shahn’s social justice works, many of which are on view in the exhibition. In 1939, Shahn denounced Father Coughlin, the Irish Catholic “radio priest,” infamous as a racist, antisemitic hatemonger who sympathized with some of Hitler’s, Mussolini’s, and Franco’s policies. The hard-hitting anti-Nazi posters Shahn made for the U.S. Office of War Information, including his rejected designs showing fascist methods of torture, give way to his more enigmatic paintings of the Cold War era, which speak to duplicitous dealings between democratic leaders and right-wing dictators.

In fact, it was during the Cold War and the Second Red Scare, when Shahn was targeted by the FBI and other entities for his left-wing activities, that he formulated his artistic credo of nonconformity. According to Shahn, nonconformity is the precondition for innovative artistic creation and great historical transformation. As he wrote in his essay On Nonconformity in The Shape of Content (1957), the nonconformist or progressive “presses for change, experiment, and venture into new ways.” He pushed against societal convention, standardization, and conformity in the postwar period. Responding to the tyranny of McCarthyism and political repression, Shahn promoted free expression and dissent, which he saw as indicative of the health of a democratic society. Fascism, for Shahn, was akin to absolutism or unchecked autocratic authority controlling all spheres of life, which was his greatest fear. His words from a 1966 interview in Response magazine sum up his convictions quite cogently: “I am filled with righteous indignation most of the time….my fear of absolutism, whether in religion, science, politics, or in art….is the strongest fear I have. And then I feel I must make a statement.”

Ben Shahn and the Abraham Lincoln Brigade

Though they are sometimes misrepresented as isolated idealists, we know that the American brigadistas emerged, like the visible part of an iceberg, out of vast and vibrant mobilized working-class communities. Communities sensitive to injustice, seasoned in solidarity and collective action, indifferent to borders. For every woman or man who walked across the Pyrenees into Spain in cardboard-soled shoes, there were tens of thousands of fighters back home who saw Braintree, Massachusetts; Scottsboro, Alabama; Flint, Michigan; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; and Belchite, Spain as battlegrounds in a single war. Their war.

For the readers of The Volunteer, Ben Shahn (1898-1969) is perhaps best understood as a rank-and-file member in this army of antifascist volunteers for freedom. A brigadista internacional who fought elsewhere and otherwise. –JDF

How did the exhibition at the Jewish Museum come about?

The Reina Sofía retrospective was not planned to travel, largely for economic and timing reasons. But when the Jewish Museum, which lent nine works to the Madrid exhibition, noted the tremendous response to the show in Spain, it became interested in “reconstituting” the exhibition for U.S. audiences. I was invited to serve as guest curator to adapt the exhibit for the Jewish Museum–an ideal venue given Shahn’s distinguished history with the institution, its rich holdings of his work, and the influential scholarship the museum has generated through pioneering exhibitions that it organized in 1976-78 and 1998-99. The Jewish Museum’s leadership understands Shahn’s significance as one of the most consequential socially engaged American Jewish artists of the twentieth century. They recognize the timeliness of Shahn’s work and how it speaks to the current moment. In fact, the exhibition has had an equally enthusiastic reception in New York–the city where Shahn was raised, educated, and politicized; the city that was central to his career as an artist. The New York press as well has been touting the exhibition as a “homecoming.”

James D. Fernández teaches at NYU and is co-editor of The Volunteer.