Book Review: Emilio Silva’s New Novel

Emilio Silva, Nébeda (Madrid: Alkibla, 2025), 212 pp. alkibla.net/nebeda/

In October 2010, standing on the edge of a ditch at the entrance to a small town in El Bierzo, León, Spain, the author of this book addressed a group of openly Republican people, and spontaneously pronounced this emblematic statement: “Here is where my silence was born; here is where my silence dies.”

He spoke these words while standing on the very earth that, for seventy-four years and five days, had covered up a mass grave containing the remains of thirteen Republican civilians who were assassinated by fascist thugs in October of 1936. One of the dead men was the author’s paternal grandfather, whose life had been torn away by a quartet of fascists. They pulled their triggers and then they left the agonizing victims lying there in the dark of night, knowing that the next morning many townspeople would have to walk past the bodies, shocked and terrorized by the sight of the massacre.

The author himself was surprised to hear his vocal chords give shape and sound to these thirteen words…

These are the opening paragraphs of Emilio Silva’s preface to his first novel, Nébeda. Right up until the end of the text, Silva refers to himself in the third person— underscoring that the right to speak on one’s own behalf, the privilege of embodying the pronoun “I,” is almost always a conquest, and ought never be taken for granted. Our contemporary debates around pronouns focus primarily on how individuals are referred to when spoken about by others. Silva, in this novel—indeed, throughout his decades-long work on behalf of Franco’s victims—reminds us that the pronoun “I” is perhaps the most precarious and contested of all. Who gets to speak in the first person?

Silva’s work as a human rights activist and his career as a novelist are intertwined. Twenty-five years ago, while he was working as a journalist, he quit his job with the idea of writing a novel that would draw on his family experiences during the Spanish Civil War and postwar. To do research for the novel, he traveled frequently to the towns of Pereje and Villafranca in El Bierzo, in the province of León, where his grandfather had been murdered and thrown into a ditch during the early months of the Spanish Civil War. Like so many descendants of Franco’s victims, he had learned to avoid self-expression; perhaps he thought at the time that the novel would be a kind of catharsis.

While Silva was gathering documentation for the novel, he met someone who claimed to know the exact location of the mass grave where his grandfather had been buried. The events set in motion by that discovery did not lead to the publication of Silva’s novel but, instead, to the exhumation of his grandfather’s unmarked grave—an event that would give rise to the historical memory movement in Spain.

The disinterment of “los trece de Priaranza” was the first scientific exhumation of a mass grave of Franco’s victims; DNA testing was used to positively identify the remains of Silva’s grandfather and namesake, Emilio Silva Faba. Ten years later, when Silva spoke to a gathering of supporters at the grave site, a movement had been consolidated. Only then did Silva feel sufficiently “authorized”—that is, enough of an author—to speak in the first person. “My pronoun,” it is as if he said, “finally, is ‘I’.” But as the memory movement expanded through the years, Silva’s novel, for a variety of reasons, would remain below ground.

Until now. The publication of Nébeda, a beautifully layered literary exploration of the Silva family’s saga, provides a fitting closure to a 25-year cycle. It’s another exhumation of sorts: another silence broken once and for all at the mouth of that grave.

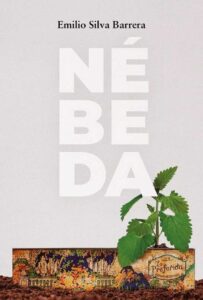

Caption: Nébeda (catnip in English) is a wild herb that grows freely in El Bierzo. It is sometimes used to flavor boiled chestnuts, the humble diet of poor peasants in times of scarcity. In the novel, the aromatic nébeda functions as a kind of fragrant key that unlocks memories suppressed over years and even generations.

Caption: Querían enterrar cadáveres, pero estaban sembrando semillas. “They wanted to bury bodies, but in fact they were planting seeds” is a sentence attributed to the great Galician artist Castelao, who represented Francoist violence in many of his Spanish Civil War Drawings.