Book Review: Elena Fortún’s Novel of the Spanish War

Elena Fortún, Celia in the Revolution, translated by Michael Ugarte (Chicago: Swan Isle Press, 2023), 278 pp.

Elena Fortún, Celia in the Revolution, translated by Michael Ugarte (Chicago: Swan Isle Press, 2023), 278 pp.

English-language readers interested in the Spanish Civil War will welcome the translation of Elena Fortún’s Celia in the Revolution, the last in the Celia young adult book series, whose twenty-four volumes remain much-loved in Spain. Although written in the 1940s, Celia en la revolución wasn’t published until 1987, well after the author’s—and Franco’s—death.

Elena Fortún was the pen name used by María de la Encarnación Gertrudis Jacoba Aragoneses y de Urquijo (1886-1952), a writer of Basque noble descent who started the Celia series in 1929. Republicans by conviction but not affiliated with any party, Aragoneses and her husband left Spain for France in 1938 and eventually settled in Argentina. During the war and postwar years, she continued to publish with Aguilar Editorial, returning to Spain in 1948 in an attempt to secure amnesty for her husband. After his suicide aborted this mission, Aragoneses returned to Argentina to live with her son, although she eventually died in Madrid in 1952.

The introduction to Celia in the Revolution by Nuria Capdevila-Argüelles explains that Aragoneses’ friend, Marisol Dorau, acted as literary executor, stewarding the writer’s voluminous papers from Argentina to Spain, where they are now housed in Madrid’ ‘s regional library. Dorau went on to shepherd both Celia in the Revolution and another manuscript, Oculto sendero (Hidden Path), to publication in the 1980s. These two hidden or “closeted” texts, Capdevila-Argüelles points out, name names and speak silences that were impossible to utter under Franco—including the duplicities of war and the reality of homosexual identities. Capdevila-Argüelles sees the metaphor of the closet as especially apt for framing Aragoneses’ intellectual journey and legacy.

But I want to focus here on the theme of orphanhood, which provides a unifying throughline as well as a domain of ethical reflection in the novel. The story makes clear that the Spanish Civil War orphaned a whole generation of Spaniards, inflicting trauma and a kind of social death. The war and its trigger-happy protagonists—on both sides—destroy the social script, disrupt a secure sense of place, and destabilize Celia’s identity. It leaves her an orphan “in the hands of God!” as she declares in the novel’s last line, boarding a boat in Valencia that she hopes will take her to safety in France.

As the novel progresses, Celia resists this loss of self by taking care of her immediate family members. Since her mother died young, before the war, she tends to her father, who was injured at the front defending the Republic, and serves as substitute mother for her younger sisters. With her friends in the neighborhood, she also cares for displaced children and teaches in Republican schools. She survives thanks to the help of kindly acquaintances and friends-of-friends, but her class standing, too, provides a shield. Still, the upper-class family from Valencia who provide Celia’s final refuge before sailing for France tell her they would not stop the Nationalists from shooting her. “I would love to forgive!” shrieks the lady of the house in agony.

In wartime, orphanhood evokes a kind of exile-in-place. Madrid is bereft, beset by warring “parents” who will shoot without regard to who gets hit. The chapters set in Madrid include some of Aragoneses’ best writing, offering penetrating details of a suffering city, its residents zombified and its neighborhoods in collapse: an alien space, anonymized and untrustworthy. Since the Civil War has torn the ground from under them, residents are forced to perform a pantomime of social relations.

The Madrid chapters vindicate the author’s choice to tell this tale as Celia’s first-person narration, allowing us to experience the war with her, including the starvation and stench. Despite everything, Celia’s resilience and intelligence shine through. She is a loyal friend and comrade, she allows the beauty of gardens and birds to nurture her soul, she adopts an abandoned kitten, and a chaste little romance buds between her and a Republican soldier. It is impossible not to tear up when Celia kneels and kisses the ground as she says a final goodbye to Madrid, her home.

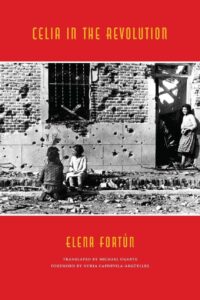

The translation by Michael Ugarte is smooth and vivid. The choice to leave the word Papá in Spanish is emotionally spot-on. The production values of this Swan Island edition are lovely and an important scholarly investment. Robert Capa’s improbable cover photograph of three young girls in Puente de Vallecas smiling in the sunshine as they sit in a street turned to rubble pays fitting tribute to the spirit of the author and her unforgettable protagonist. Another beautiful gesture in this edition is a facsimile of the manuscript’s first page, included as an extra frontispiece. It lends intimacy to the book, hinting at the ways in which Celia’s story is also the author’s.

Patricia A. Schechter is a Professor of History at Portland State University whose work focuses on Spain, women’s history, public history, and transnational history. Her book “El Terrible”: Life and Labor in Pueblonuevo, 1887-1939 (Routledge, 2025) situates a story of an Andalusian mining town in the global events that defined the twentieth century.