“As a Documentary Genre, the Graphic Novel Offers Huge Advantages”–Paco Roca

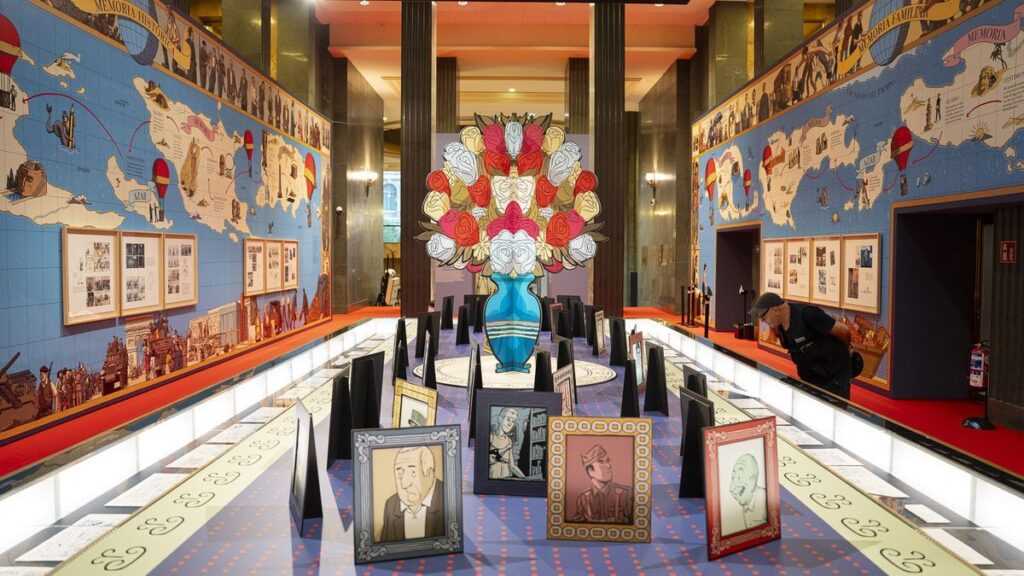

Paco Roca, one of Spain’s best-known graphic novelists, was honored this summer with an exhibit at the headquarters of the Instituto Cervantes in Madrid. His latest book tells the true story of a woman who goes in search of the remains of her father who was executed by the Franco regime and buried in a mass grave.

If the Spanish graphic novel has come of age, it is due in no small part to the Valencian writer Paco Roca. Over the past thirty years, his work has developed from gritty underground comics into award-winning, book-length stories that explore life under Francoism, the devastation of Alzheimer’s, or the legacies of the Spanish Civil War—as well as self-deprecating autobiographical takes on his own daily struggles as a graphic artist in twenty-first-century Spain.

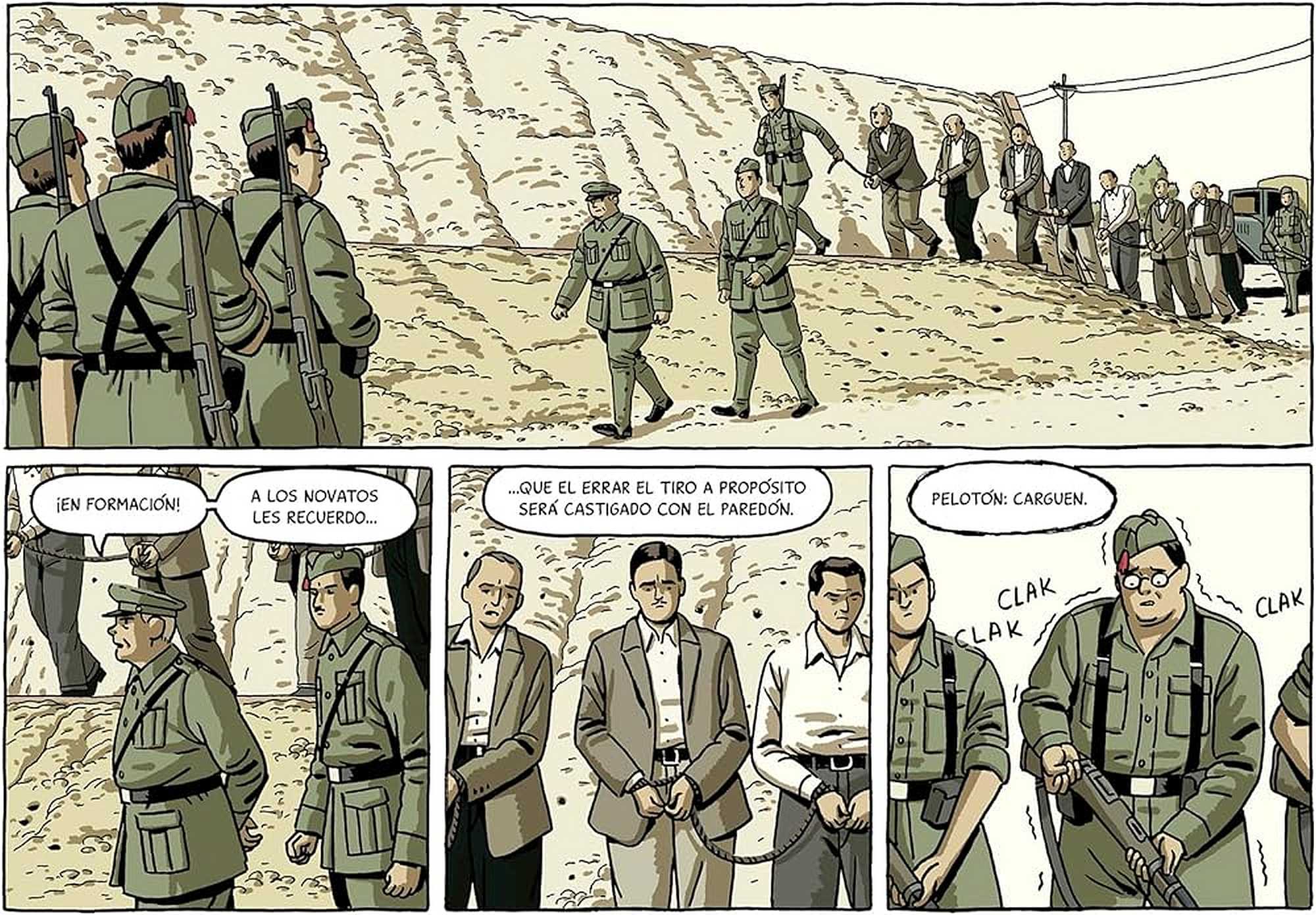

Some of Roca’s best-known titles include Arrugas (Wrinkles, 2007), whose main character lives with dementia; El invierno del dibujante (The Winter of the Cartoonist, 2010), about a group of rebel comic artists in Francoist Barcelona; Los surcos del azar (Twists of Fate, 2013), about the Spaniards who helped liberate France from the Nazis (a story inspired by the work of ALBA’s own Robert Coale); and, most recently, El abismo del olvido (The Abyss of Forgetting, 2023), written with Rodrigo Terrasa. A 300-page tour de force, El abismo tells the true story of Pepica Selda, a woman in her eighties who goes in search of the remains of her father, José, who was executed by the Franco regime in 1940 and buried in a mass grave.

Roca, who turned 56 this year, has had his books translated into thirteen languages. He was honored this summer with an eye-catching exhibit at the headquarters of the Instituto Cervantes in Madrid. The Volunteer spoke with him in July.

What place did comics have in your life when you were growing up?

A very important one! For as long as I can remember, I liked drawing and telling stories. I really wanted to be a cartoonist like Walt Disney. But at that time, unlike today, making movies was not something a middle-class kid could do easily. So instead, I started drawing comic strips, which I read all the time, starting with those published by Bruguera, like Mortadelo y Filemón or Zipi y Zape. Later, I moved on to Franco-Belgian series like Astérix and Tintin, superhero comics, and to what was then called comics for adults, like Moebius. Comics have always spoken more to me than regular novels. After all, the artists bring you in direct contact, right there on the page, with entire worlds they have created visually—something that movies can do today with digital effects, but that, back then, only comics could.

When we were kids, comics were not considered “serious” reading.

Yes, I also grew up with my parents telling me to stop reading comic strips already and pick up a “real book” for once. (Laughs)

That’s perhaps why they often had a subversive charge.

That’s perhaps why they often had a subversive charge.

Absolutely. In fact, my teenage years coincided with the height of Spanish underground comics, which were published in magazines like El Víbora. The stories in there touched on all the themes of our daily lives on the street: sex, alcohol, rock and roll, relationships of all kinds. The authors clearly lived in the same world as we did. Their characters even talked like us.

Is that subversive element weaker now?

Well, thanks to the format of the graphic novel, we certainly have earned a kind of respect that we didn’t use to have outside of the world of comics, which wasn’t considered to be at the same level as film or serious literature. Even when adult comics emerged in the 1970s and eighties, the stories remained quite self-referential. They were still mostly about adventures, mysteries, and the like—just with more sex and violence than the series written for kids. More importantly, they were restricted to set formats: series of albums of between 46 and 54 pages each. That was all that the industry—that is, the French market—allowed for at the time. For the artists, that format was quite restrictive. Moreover, the kinds of stories that filmmakers and novelists had long been able to tell, including nonfiction and autobiography, were considered off limits. The graphic novel, by contrast, is not bound to any particular format, style, length, or genre. It allows for longer stories and albums that are not necessarily part of a series—but it also gives you the option, for example, to include less exuberant drawings in order to privilege the story.

What has this freedom meant for you?

Well, for one, it means that I no longer depend on the French market. In the past, if you wanted to make a living as a comic artist, you had to write for the French comics industry. I can tell you that if I’d continued to depend on France, I wouldn’t have been able to write most of my books.

Did departing from those set formats, as you did with Wrinkles, feel like a risk at the time?

In reality, the big change, for me, came a bit later, with The Winter of the Cartoonist. Both Wrinkles and Calles de arena (Sandy Streets) were books I wrote for a French publisher who had just started a small line of graphic novels. The first thing they told me was that there was no way this format was going to make any money. What happened, though, was that Wrinkles became a huge commercial success in Spain. Calles de arena did very well, too. It was then that I discovered that my market wasn’t in France, but in Spain. At that point, my Spanish publisher, Astiberri, and I decided to see if we could publish something directly in Spanish. In that sense, The Winter of the Cartoonist certainly was a risky bet.

Did the American graphic novel help create space for new formats in Spain? I’m thinking of Art Spiegelman’s Maus, for example.

To some extent, yes. I think three books in particular helped expand the reading public for graphic novels in Spain: Spiegelman’s Maus, Mariane Satrapi’s Persepolis, and Frank Miller’s 300. Then, in 2007, Miguel Gallardo published María y yo (Maria and I), and I published Wrinkles, both of which expanded the Spanish audience even further. We reached readers who had never picked up a comic book before.

You said that the format of the graphic novel removed old restrictions. I’m curious if it also introduced new ones. Much of your recent work has a didactic component, for example. Does that feel like a burden? I mean, it’s one thing to want to entertain your readers, but quite another to educate them.

You said that the format of the graphic novel removed old restrictions. I’m curious if it also introduced new ones. Much of your recent work has a didactic component, for example. Does that feel like a burden? I mean, it’s one thing to want to entertain your readers, but quite another to educate them.

Educating my readers? Honestly, that’s overstating it a bit. What I do as a writer, I feel, is to look for stories I’d like to explore and think about. I simply bring the reader along with me in that process. Take Twists of Fate: when I first heard the story of the Spaniards who helped liberate France, I was blown away. I wanted to know more about it, and writing the graphic novel was my way of doing that. The Abyss of Forgetting, on the other hand, is a purely journalistic project. In Twists, I still felt compelled to mix in some fiction—the Paco character who interviews the aging Miguel—but in Abyss, I wasn’t afraid to let go of the fictional element altogether. As a documentary genre, I honestly feel that the graphic novel offers huge advantages because it combines the best of non-fiction books—the pace and density of information—with the best of documentary film: the ability to tell part of the story visually.

Spain is politically polarized, and the topics you touch on are controversial. I imagine some of your readers balk at your historical-memory-themed books.

Strange though it may sound, I wasn’t aware of the political aspect of my work at first. Although I’ve always thought of myself as a person on the left, my politicization has been rather gradual. Wrinkles, for example, is a totally apolitical story. And while it’s true that the main characters of The Winter of the Cartoonist are victims of the Franco regime, the story itself is not very political at all. When I did the research for Twists of Fate, I learned a lot I didn’t know about the Francoist repression and Republicans’ role in World War II—but even then, I was surprised when readers told me they thought the book took a political position. For me, in the end, it’s a deeply patriotic story: after all, it’s about Spaniards who help conquer fascism in Europe! But you’re right that when you start talking about the exhumations of mass graves, as I do, there are going to be readers that are not going to buy your book, even if they bought your books in the past. That said, in Spain, The Abyss has sold 80,000 copies. I know that I’ve reached some folks who might not have engaged with the topic otherwise.

And then you have your readers abroad.

It’s funny that you mention that. Although the foreign market is much less important for me financially than my Spanish readership, it is true that I never sit down to write for a Spanish audience. When Rodrigo Terrasa and I began working on The Abyss, I told him: “Our readers are going to be largely Spanish, but we are still going to write this story as if we were telling it to someone from Poland or Turkey.” For a topic like the mass graves, that approach works very well. It widens your perspective and prevents you from being distracted by details that are too local or ephemeral, too tied to the current moment. I want my books to still make sense twenty years from now.