Arkivo: What Language Is This?

The title of this new occasional feature of The Volunteer is the Esperanto word for “archive.” In it, we will present, translate, and contextualize iconic non-English language documents related to the anti-fascist struggle in Spain. If you have a favorite document in a language other than English, please let us know!

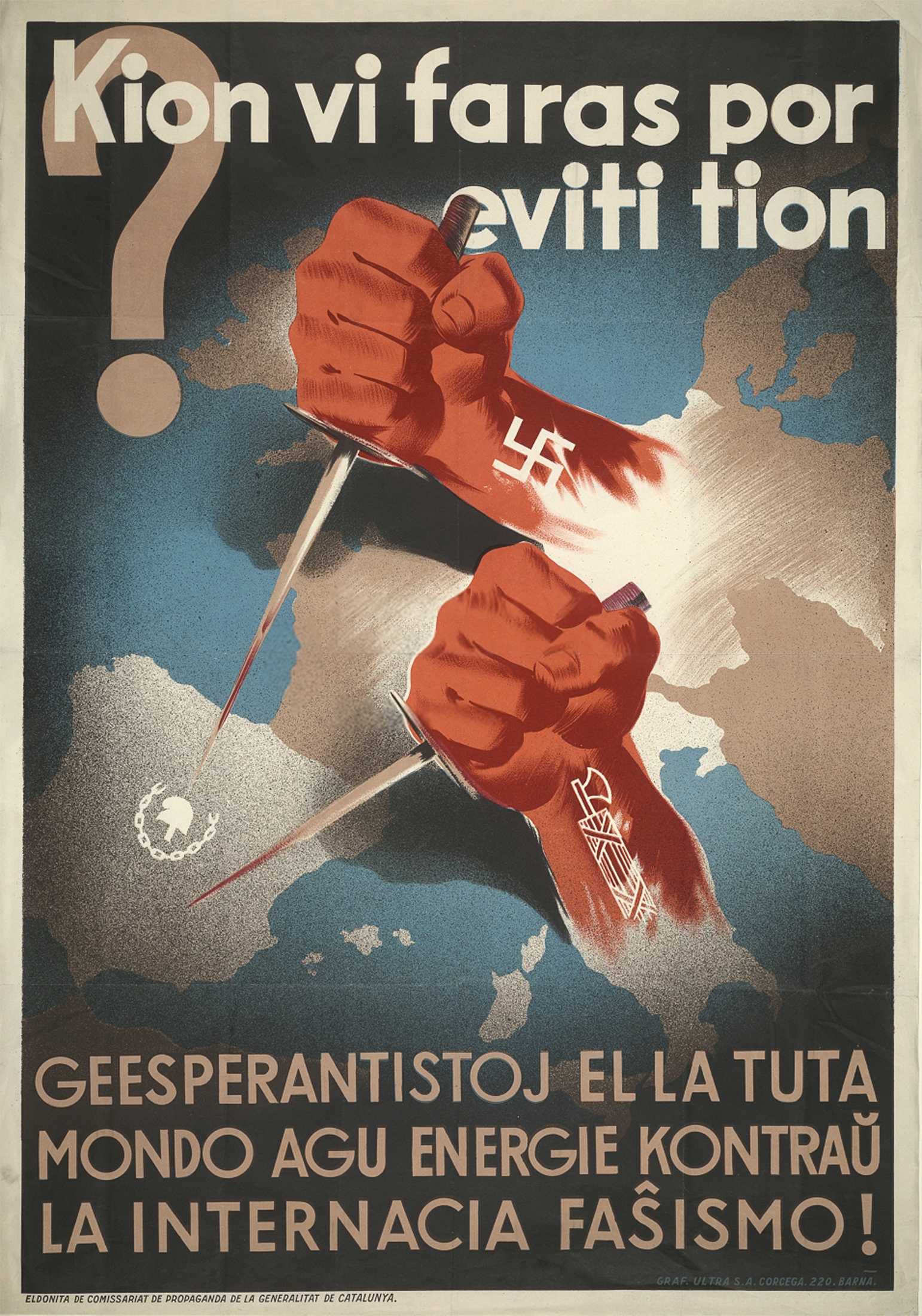

This issue’s document is a poster produced by the Propaganda Office of Catalonia in 1936, with a text in a hard-to-identify language. Can you tell what language it is? Can you make out the caption?

When I teach the Spanish Civil War to my undergraduates, I always highlight the fact that Republican propaganda was produced in many different languages. This leads to an exploration of how the Republic’s struggle was, among other things, a battle for the hearts and minds of anti-fascist citizens all over the world. Abandoned by its non-interventionist sister democracies (England, France, the US), the Republic was forced to use propaganda—photography, documentary film, and posters, for example—in an attempt to appeal directly to the women and men of different nations, often in their own languages.

The financier and philanthropist George Soros (Hungary, 1930) learned Esperanto from his father, Tivadar Soros, a prominent Esperantist and author. Tivadar organized Esperanto clubs, wrote both a novel and a memoir in the language, and even chose the family name “Soros” because in Esperanto it means “will soar.” The Soros family was deeply connected to the Esperanto movement in interwar Hungary, with their home serving as a gathering place for Esperantists. Further reading here.

The linguistic diversity of my students almost always makes for an animated session, as we try to decipher the captions of Spanish Civil War posters together. I can usually count on having some Spanish and French speakers in my class. If I’m lucky, there might be a student who can recognize and translate Catalan. Occasionally, a student will have a rudimentary knowledge of Yiddish and can at least identify the language, if not readily translate from it. But this poster almost always stumps everyone. The students can usually decipher the message, piecing together their knowledge of different languages, but they almost never can correctly identify the language itself: Esperanto.

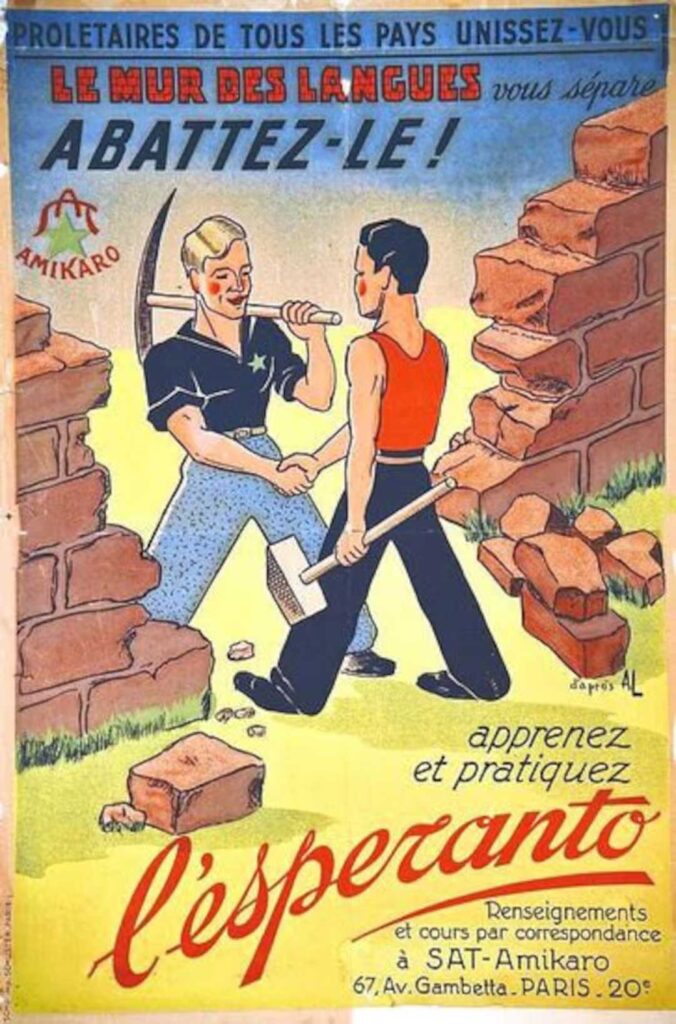

It was in 1887, in the babelic town of Bialystock (then part of the Russian Empire, now part of Poland), that a Jewish ophthalmologist named L.L. Zamenhof published a pamphlet describing a language he had spent years inventing. The publication was titled “Unua Libro”—First Book—and Zamenhof signed it with a pseudonym that eventually would be used to designate the language itself: Doktoro Esperanto. The hope that underwrote Zamenhof’s project was that an easy-to-learn second language—with only 16 basic rules and no irregular verbs—would promote world peace and understanding. Dr. Esperanto’s dream struck a chord, and soon there were large numbers of Geesperantisitoj all over the world, acquiring and promoting the language through courses, clubs, congresses, pen pal networks, and publications. By 1905, thousands of adherents from Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Africa convened for the first World Esperanto Congress in Boulogne-Sur-Mer, France—proof that Zamenhof’s dream was resonating with a broad international audience.

It was in 1887, in the babelic town of Bialystock (then part of the Russian Empire, now part of Poland), that a Jewish ophthalmologist named L.L. Zamenhof published a pamphlet describing a language he had spent years inventing. The publication was titled “Unua Libro”—First Book—and Zamenhof signed it with a pseudonym that eventually would be used to designate the language itself: Doktoro Esperanto. The hope that underwrote Zamenhof’s project was that an easy-to-learn second language—with only 16 basic rules and no irregular verbs—would promote world peace and understanding. Dr. Esperanto’s dream struck a chord, and soon there were large numbers of Geesperantisitoj all over the world, acquiring and promoting the language through courses, clubs, congresses, pen pal networks, and publications. By 1905, thousands of adherents from Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Africa convened for the first World Esperanto Congress in Boulogne-Sur-Mer, France—proof that Zamenhof’s dream was resonating with a broad international audience.

Though there was nothing inherently political or ideological about Esperanto, the language held special appeal for utopian thinkers, including anarchists and other idealistic radicals on the Left. Notably, in Mein Kampf, Hitler rails explicitly against Esperanto, linking it to what he called the Jewish conspiracy to internationalize the world and to bring about a global mixture of races. Zamenhof’s family was, in fact, targeted by the Nazis, and his children were murdered during the Holocaust.

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), the Republicans—particularly, though not exclusively in Catalonia—used Esperanto as a tool in their propaganda strategy to foster international support and solidarity.

The poster reads: “What are you doing to avoid this? Esperanto-speakers of the Entire World: act with force against international fascism.”