Antifascist Autobiography in Red-Baiting America: The Shifting Stories of Salaria Kea’s Life

On November 8, 1937, Salaria Kea, a 26-year-old African American nurse from Ohio, had been in Spain for seven months and one day. The country was in disarray. Half its territory was controlled by fascist rebels. Cities were being bombed, and civilians were killed by the thousands. Thousands more were forcibly displaced. But Kea felt in her element. She knew she was doing important work. She’d spent most of her time logging long hours at Villa Paz, a former summer estate of the Spanish King—who’d fled the country in 1931, just as it turned into a Republic—that she had helped convert into a proper army hospital with 250 beds. The stream of wounded soldiers was constant.

Spain had been at civil war since July 1936, when a right-wing military rebellion had tried to overthrow the democratically elected government of the Popular Front, which had won the elections in February of that year with a program for progressive reform that had rubbed the country’s powerful conservative elites—the army, the rich landowners, and the Catholic church—the wrong way. But their planned coup had failed to control the largest cities. Instead, it had unleashed a war.

From day one, the fighting in Spain commanded the attention of global public opinion, not unlike the war in Ukraine today. Then as now, many thought that the fate of the entire world hung in the balance. Yet unlike Ukraine, the Spanish Republic was not backed by other democracies, most of which signed on to a non-intervention pact. Only the Soviet Union (and to a much lesser extent, Mexico) provided some military support. The rebels, meanwhile, united under the command of General Francisco Franco, could count on significant military assistance from Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy—showing that the nonintervention pact, which both countries had joined, was a scam from the outset. While Great Britain and the United States blocked the Republic’s access to arms, moreover, companies like Texaco supplied the rebels with fuel.

How to interpret the war in Spain became a point of intense dispute across the Western world. Catholics and others on the Right saw the conflict as a battle between civilization (the Francoists) and godless Communism (the Republicans). Most on the Left saw the war as a battle between democracy (the Republic) and fascism (the Francoists). It was under this banner that, in the fall of 1936, the Communist International proposed organizing a contingent of international volunteers to help stop fascism in its tracks. In an unusual expression of international solidarity, between 35,000 and 40,000 individuals from around the world responded to the call, serving as soldiers, pilots, ambulance drivers, and medical personnel.

American Medical Bureau: Sailing on the SS Paris 16/01/1937. back row left: Mildred Rackley, Taos, New Mexico; Dr. Nathan Bloom, New York; Dr. Albert Byrne, San Francisco; Dr. Edward Barsky, New York; Dr. Edwardo Odio y Perez, Havana, Cuba; Harry Wilkes, New York; Dr. Phil Goland, Cincinnati; and Helen Freeman, Brooklyn, N.Y. front row left: Lini Fuhr Paterson, N.J. Salaria Kea, New York; Frederica Martin, New York; Ray Harris, New York; Anna Taft, Brooklyn, N.Y.; and Rose Freed, New York.

Salaria, who had graduated from Harlem Hospital, New York, three years earlier, was the only Black nurse serving in Spain, where she’d traveled as part of a group of US medical professionals sent by the American Medical Bureau to Save Spanish Democracy. Her reputation preceded her, and among the 90 or so other Black volunteers from the US who were serving on the Republican side—mostly as soldiers—she became something of a legend; she made an appearance in two documentaries as well, including a film by Henri Cartier-Bresson. She’d spend a total of 13 months in Spain, returning to the US on May 16, 1938.

On that November 8, half a year earlier, Kea had filled out a brief application to join the Spanish Communist Party (PCE). (The filled-out form for “Comrade Salaria Kee” is kept at the archive of the Communist International in Moscow.) Asked about her party membership in the US, she indicated that she’d joined the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) in Harlem, New York, in 1935. This was not surprising: the majority of the 2,800 US volunteers who went to Spain were in some way affiliated with the party or its youth movement. Yet 43 years later, when Kea was interviewed for an oral history about Americans in the Spanish war, she vehemently denied any connection to the CP. “I was no Communist because I didn’t even know what Communism was,” she said. “I thought it was for white people only, just like … the mafias.”

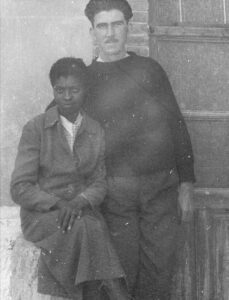

The interview took place on June 7, 1980 in the apartment in Akron, Ohio, that Kea shared with her Irish husband, John “Pat” O’Reilly, whom she had married in 1937 in Spain, where he was also serving as a volunteer. The interviewer was the historian John Gerassi, who was working on his oral-history collection The Premature Antifascists, which would come out in 1986. The two-hour recording of the conversation is kept at the Tamiment Library in New York City.

Toward the end of the session, the subject of religion in France and Italy came up. “France was a Catholic country when I was there,” Kea said. “I forget what percentage [are Catholic] now in France—and the Pope has been over there trying to bring the people back. … And do you know Italy is changing also? Can you imagine … the Italians and Italy are turning Communist? … That’s what’s happening. It comes out of my own paper—not the regular newspaper, the Catholic paper…”

Kea’s passionate profession of her faith prompted Gerassi to inquire about the anticlericalism among Spanish Republicans, on whose side, after all, Kea served in the war. As the Republicans sought to turn Spain into a modern, secular country, they faced strong opposition from the Church hierarchy. Franco, on the other hand, presented himself as the champion of tradition and Catholicism, a claim promptly endorsed by the Vatican. Franco won the war in April 1939 and would rule Spain as a military dictator until his death in 1975.

“But you didn’t find that the people were against Catholics in Spain?” Gerassi asked. “Because the Communist Party was quite…”

“I know it, and there was Catholics there,” Kea interrupted. “Pat was no Communist,” she said, in reference to her husband. And then she added the phrase we already heard: “I was no Communist because I didn’t even know what Communism was.”

After the interview was over and Gerassi had left the building, he took a moment to record his impressions of Kea, which take up the final minutes of the tapes. Reflecting on her involvement in Spain, he remarked:

She’d done it under the auspices of Catholicism and religion and had … definitely mixed up the sides and the politics and the religion in the Spanish war itself, where she had totally gone along with the whole process when she had arrived. I don’t think she’s at all political and I don’t think she was then, except in a sort of a humanist way. I don’t think she ever will be.

Based on the long interview, in which Kea referenced her faith constantly, Gerassi’s conclusion certainly seemed plausible. Yet the archival record tells a different story—one that undermines both Kea’s characterization of herself in the late 1930s as a politically naïve young woman driven mostly by religious zeal and Gerassi’s description of her as “not at all political.”

As we saw, the membership request form for the Spanish Communist Party suggests that Kea, who at the time was an outspoken young activist for racial justice, was closely associated with the CPUSA at least from 1935. But there are more clues. After her return to the States, Kea became a prominent spokesperson for the Spanish Republican cause and associated with well-known party members and fellow travelers. She also frequently appeared in the CPUSA newspaper, The Daily Worker; participated in the 10th Convention of the CPUSA, held in New York in May 1938; and was a keynote speaker at the inaugural meeting of the CP-controlled organization Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (VALB) in December 1939.

The precise nature of Kea’s politics is one of many blurry areas in her biography. As the only African American nurse to join the medical volunteers, Kea’s name is among those most often cited in studies and documentaries about the US contingent in Spain. She’s also featured in overviews of Women’s and Black History. For a while, in the late 1930s, she was nothing short of a national celebrity, appearing side by side with the likes of Langston Hughes, Paul Robeson, Cab Calloway, Count Basie, and Fats Waller. Outside of that relatively narrow spotlight, however, much of her life remains shrouded in mystery. Many details in her biography are vague or contradictory, from her place or date of birth and her upbringing to her experiences in Spain and the evolution of her political and religious views. Even the spelling of her last name is unclear.

What explains this persistent vagueness? For one thing, the stories Kea told about her life, recorded by journalists and scholars, changed over time, often in significant ways. This is not surprising: Kea was a poster child for controversial political struggles—antifascism, internationalism, and racial justice—whose memory was shaped decisively by the political context of each moment, including the Cold War. This meant her narratives were susceptible to manipulations, restrictions, and taboos. If, say, presenting oneself as a deeply religious person would have been uncommon among the radical Left in the 1930s, in the United States of the 1950s and ‘60s any association with the Communist Party would have been reason for suspicion and persecution in professional circles and civilian life. Still, the single most important factor to explain the ambiguities in Salaria Kea’s life story may be her status as a working-class, female, Black progressive activist in an environment that, for most of her life, was profoundly anti-Communist, racist, and sexist.

Still, despite the challenges the historical record poses to Kea’s biographers, it’s useful to attempt to reconstruct the course of her life, ambiguities and all. Not only because that life is rich and interesting in its own right, but also because it may help nuance, complicate, and deepen our understanding of what drove Kea and her close to 3,000 fellow volunteers from the United States to serve in the Spanish Civil War. More generally, investigating Kea’s life, and understanding the gaps in her narrative, will also help us understand how the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (as the US contingent in Spain came to be known) has been remembered—or forgotten—since the first US volunteers left for Spain in late 1936.

***

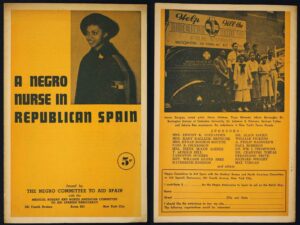

The first detailed description of Salaria Kea’s formative years can be found in a 5,000-word pamphlet, A Negro Nurse in Republican Spain, which came out in August 1938. Although it was published without author credit, Anne Donlon has argued that it was written by Thyra Edwards (1897-1953), an African American journalist, social worker, and progressive activist some 15 years Kea’s senior. Edwards, who had been involved with fundraising efforts for the Spanish Republic, had also traveled to civil-war Spain. In the summer and fall of 1938, she accompanied Salaria on a 21-city lecture and fundraising tour across the United States.

The pamphlet, which came out right around the time the tour kicked off, tells the story of Kea’s development of political consciousness against the backdrop of her lifelong experiences with racism and a newfound interest in international politics. Salaria, we read, was born in Georgia, into a poor family. Her father, who worked at the state mental hospital, died a violent death when Salaria was only an infant. Not much later, Salaria moved to Akron, Ohio, with her three brothers and her mother. After a couple of years, her mother returned to Georgia, leaving her children with several Akron families. At school, Salaria’s aspirations were thwarted by segregation. She had to transfer to a different high school to play basketball because her school did not allow Black girls on the team. And when, after working summers with a local Black doctor, she expressed interest in a nursing career, Ohio universities told her they did not accept African Americans. On the doctor’s recommendation, she applied to the Harlem Hospital School in New York, where she enrolled in 1931.

The pamphlet, which came out right around the time the tour kicked off, tells the story of Kea’s development of political consciousness against the backdrop of her lifelong experiences with racism and a newfound interest in international politics. Salaria, we read, was born in Georgia, into a poor family. Her father, who worked at the state mental hospital, died a violent death when Salaria was only an infant. Not much later, Salaria moved to Akron, Ohio, with her three brothers and her mother. After a couple of years, her mother returned to Georgia, leaving her children with several Akron families. At school, Salaria’s aspirations were thwarted by segregation. She had to transfer to a different high school to play basketball because her school did not allow Black girls on the team. And when, after working summers with a local Black doctor, she expressed interest in a nursing career, Ohio universities told her they did not accept African Americans. On the doctor’s recommendation, she applied to the Harlem Hospital School in New York, where she enrolled in 1931.

Although the hospital had both Black and white staff, the cafeteria was segregated, a situation that Kea and a group of other nurses protested, with immediate success. This episode, the pamphlet reads, “was Salaria’s first experience in-group action, in organized, programmatic resistance to injustice. … [S]he was learning to resist, to organize and change conditions.” In the years following, Kea combined her professional development with activism and a political education. She graduated in 1934, and soon joined the staff at Harlem Hospital, where she continued to denounce conditions and effect change. “Salaria,” the pamphlet says, “learned that the individual is only as secure as the group.” Together with “the more progressive nurses” she “attended lectures and discussions on civic affairs, local, national, international. These discussions helped her to understand what was happening in Harlem and its relationship to events in Europe and Africa.”

Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in the fall of 1935 once more compelled her into action: “With groups of Harlem nurses and physicians, she assisted in gathering the first two tons of medical supplies and dressings sent from this country to Ethiopia. She was active in the drive Harlem physicians initiated and which resulted in a 75-bed field hospital being sent to Ethiopia.” When, in the summer of 1936, the military rebellion against the Spanish Republic was backed by Mussolini, Salaria “understood that this was the same fight. She had developed enough to understand it.” And she decided to volunteer. The pamphlet goes on to describe Kea’s work in Spain, first at the Villa Paz hospital southeast of Madrid, then at the Teruel front, during the retreat from which she briefly lost contact with her unit, and finally in at a hospital near Barcelona, where she was hurt in a bombardment and given permission to return to the United States. Throughout, the text underscores Kea’s persistence, ingenuity, and altruism.

By the time she returned from Spain, Salaria Kea was already a household name, at least among African Americans and the radical Left. Several journalists who had traveled to Spain, including Langston Hughes and Nancy Cunard, had written about her for the Black press; she’d also been featured in The Daily Worker, the Communist daily newspaper. Two episodes covered in the papers that did not make it into the pamphlet were her marriage to John O’Reilly in October 1937 (reported in December by Langston Hughes for the Baltimore Afro American), and the time Salaria, lost from her unit, was mistaken for a North-African mercenary fighting for Franco and spent a night in jail (covered in The Daily Worker in May 1938).

From the records in Kea’s file at the Tamiment Library (NYU), the broad outlines of her life after Spain emerge. Once she’d concluded her lecture tour, Kea resumed her duties at Harlem Hospital; the April 1940 census lists “Salaria K. O’Reilly,” 28, as a charge nurse there. That same year, she was joined in New York by her Irish husband, who went on to enlist in the US Army during World War II. Toward the end of the war, Kea herself served in the US Army Nurse Corps in France. After 1945, Pat and Salaria continued to live in New York City, where Salaria earned an education degree at NYU. The couple had one child, who died as an infant. For the next twenty years, she worked and taught at half a dozen different hospitals while Pat served as a railroad engineer for the Transit Authority. Kea retired in 1966. In 1968, she enrolled in a Creative Writing program at the Palmer Writers’ School in Minneapolis. In 1973, the couple moved back to Akron. Pat died in 1987; Salaria in 1990.

Throughout the decades following the war, Kea assembled several accounts of her life, which are preserved in archives in New York and London. Some extracts from these accounts were published as part of magazine articles: the Cleveland Magazine featured her and Pat in 1975; Health & Medicine ran a biographical piece in 1987; and the Akron Beacon Journal did the same not long after her death, in 1991. Meanwhile, in the late 1960s or early 1970s, she’d provided biographical information to Frances Patai, who was writing the history of the US medical personnel in Spain. In 1977, she and her fellow nurses were honored by the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in San Francisco, who also issued a reprint of the 1938 pamphlet. In 1980, as we know, she was interviewed by Gerassi. A couple of years later, she talked about her life in The Good Fight (1984), a documentary about the Lincoln Brigade.

The longest of the written biographical accounts assembled by Kea is a 48-page typescript that is at the Tamiment Library. Like the 1938 pamphlet, this text is largely narrated in the third person, with long first-person quotes. It contains everything the pamphlet contains, although many episodes are described in more detail, suggesting that it draws on an earlier, longer draft of Thyra Edwards’ text. Yet the typescript also incorporates other elements: a one-page prologue and a dedication page, and, later in the text, about four pages that transcribe sections from an article about Kea by Nancy Cunard published in January 1938.

The archival documents, magazine articles, and oral history interviews are complementary, but they also contradict each other. Among the most salient discrepancies are Salaria’s place of birth (generally cited as Milledgeville, Georgia but sometimes as Akron), her year of birth (cited as 1910, 1911, 1913, or 1917), the death of her father (which at least once she associates with a World-War-I shipwreck rather than a stabbing at the mental hospital), the details of her transatlantic voyage in 1937 (in some cases, she states that the doctor leading her group refused to sit at the same dinner table as a Black nurse), and the details of her time in Spain—in particular, her capture and imprisonment. As we saw, the US press had written in May 1938 about Kea getting lost, being misidentified as someone associated with the Francoist forces, and arrested by the Republicans, who jailed her for a night—an episode omitted from the pamphlet. In the 48-page typescript, the story has changed: Kea claims that she was arrested by two German soldiers, locked into a dungeon four stories underground, forced to watch an execution, and freed the next day by the International Brigades. In the conversation with Gerassi, the story changed yet again: now Kea said she’d spent seven weeks in the dungeon, where she’d passed the time reading her Bible (which had been secretly returned to her by friendly German lady), witnessed multiple executions, and was finally rescued by a monk, who brought her back to the International Brigades.

As time passed, Kea’s accounts of her life up to and including the war in Spain not only became more detailed but also increasingly literary, even cinematic. Not surprisingly, some of her versions have been disputed. The racist incident on the boat from New York to France, in March and April 1937, is a case in point. “During her journey to Spain,” the 48-page manuscript reads, “the doctor in charge of the group refused to sit at the same table with Salaria in the dining room and demanded to see the captain. The captain came and removed Salaria to his table, where she remained throughout the voyage.” (In the 1975 interview for Cleveland Magazine and in the conversation with Gerassi, the episode was told in further detail). Two women who did extensive research on the US medical personnel in Spain, Frances Patai and Fredericka Martin (who’d served as a nurse in Spain herself), refused to believe Kea’s story, in part because it had not been mentioned by any of the other members in the group. Kathryn Everly notes Fredericka Martin’s marginal notes in a copy of Kea’s texts, indicating her stories were “false” or “exaggerated.” “It’s all a figment of her imagination, as is her story of being captured and then escaping from the Germans,” Patai wrote to a Spanish Civil War veteran who was part of the group, in a letter cited by Robert Reid-Pharr. Patai assured her correspondent she would leave the episode out in her own work: “none of us want such an untrue lie to dim the glory of the U.S. volunteers.”

To other scholars, however, Patai and Martin were too quick to dismiss Kea’s story. Sharpe points out that Gerassi’s interview with Evelyn Hutchins, who worked as an ambulance driver, confirms that the doctor in question was a problem because “he used to refuse to sit at a table with Salaria.” Reid-Pharr suggests that an incident like the one Kea describes would have been “quite plausible.” Martin had tried to persuade Salaria to postpone her marriage with O’Reilly, Aelwyn Wetherby writes, a push that Kea read as racial discrimination. For Emily Robins Sharpe, the whole thing reeks of censorship: “directors and editors allow her to discuss interracial solidarity but not her own personal experiences of its opposite.”

To other scholars, however, Patai and Martin were too quick to dismiss Kea’s story. Sharpe points out that Gerassi’s interview with Evelyn Hutchins, who worked as an ambulance driver, confirms that the doctor in question was a problem because “he used to refuse to sit at a table with Salaria.” Reid-Pharr suggests that an incident like the one Kea describes would have been “quite plausible.” Martin had tried to persuade Salaria to postpone her marriage with O’Reilly, Aelwyn Wetherby writes, a push that Kea read as racial discrimination. For Emily Robins Sharpe, the whole thing reeks of censorship: “directors and editors allow her to discuss interracial solidarity but not her own personal experiences of its opposite.”

While it’s hard to know what exactly happened on the boat, other ambiguous chapters of Kea’s biography are easier to clarify. She was born not as Salaria but as Sarah Lillie Kea, most likely in 1911. The death of her father at the mental institution in Georgia, around 1912, seems much more plausible than his death at sea during World War I. Central State Hospital, which had opened in in 1842 as the Georgia Lunatic Asylum, continues in operation to this day in Milledgeville. Nor is there reason to doubt Kea’s accounts of structural racism in Akron—a city known for its powerful Ku Klux Klan, which emerged precisely in the 1910s and ‘20s. Dr. B.N. Riddle, who recommended Salaria go to New York, also existed: he had started practicing in Akron in 1928 at 251 N. Howard St. The April 1930 census, finally, has “Sarah L. Kee,” 18, living with her brother and his family at 394½ Livingston St. in Akron.

The most interesting and transformative time in Kea’s life is the six years she spent in New York City before leaving for Spain, from 1931 to 1937. In the midst of the Great Depression, the political climate was heady. The city was teeming with radical left organizations, often connected with racial and ethnic groups: Puerto Rican, Cuban, Spanish, Dominican but also the African American community, which mobilized, and saw itself politicized, around the trial of the Scottsboro boys (nine Black teenagers falsely accused of raping two white women on a train near Scottsboro, Alabama, in 1931), the Harlem riots of March 1935, and the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in October 1935. Healthcare—where African Americans suffered structural discrimination and insufficient resources—was a central concern in the Black community. In early 1933, attention centered on the situation at Harlem Hospital, where Kea had enrolled a year and a half earlier.

In January, the Harlem branch of the CPUSA in New York stated it would “support a movement to do away with discrimination against Negro doctors, nurses, and patients in Harlem Hospital and all hospitals in New York City,” Mark Naison explains. Rejecting a committee appointed by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) as a whitewashing attempt, the CP instead encouraged the election of a “People’s Committee” to investigate discrimination against staff and patients at the hospital. The committee was formed and had regular public meetings. By late 1936, Mark Naison writes,

sparked by a rash of deaths in the infant ward of the hospital, Party members on the hospital staff joined with Communist neighborhood organizers in a picket line at the hospital. After several weeks of demonstrations, the hospital hired new infant nurses, began isolating sick infants, and issued new linen daily. From this point on, the Harlem Hospital branch became the largest and most dynamic Party “shop unit” in Harlem. Led by [an African American] nurse named Rose Gaulden, it grew to a membership of over fifty, composed of doctors, nurses, and nonprofessional workers, and agitated for the unionization of the hospital staff, the improvement of its facilities, and an end to discrimination in the city hospital system. “We had all the doctors (only two or three who weren’t),” Abner Berry [a Black party organizer] recalled, “and two or three dentists. At Harlem Hospital, we had practically all the nurses. That was one of our biggest branches —a nurses’ branch.”

It is quite likely that Salaria Kea entered into the CP’s orbit around 1933—a couple of years earlier, that is, than her reported entry into the party in 1935. Reading between the lines, in fact, the 1938 pamphlet states as much. In a sentence like “Salaria learned that the individual is only as secure as the group,” the “group” likely refers to the Party. And stating that her “activities centered with the more progressive nurses” indicates that she began associating with Party members among the nursing staff. Of these, as we just saw, there were many.

Why did Kea deny all this in later years? Why did she and the others who wrote the story of her life change or leave out so many important details? For the 1938 pamphlet, the answer is relatively straightforward. Thyra Edwards’ text had a very clear purpose: to raise funds for the Spanish Republic among as broad as possible a segment of the population. Following the tactic of the Popular Front, officially adopted by the Communist International in 1935, it sought to build a broad anti-fascist alliance that could not afford to alienate those sectors of society who may have felt queasy about Communism. This explains why the text is coy about Salaria’s party affiliation at Harlem Hospital.

The pamphlet had two rhetorical goals. It sought to prove that the Spanish Civil War was connected to the Ethiopian cause and, therefore, to the fate of African Americans. It also sought to portray the Spanish Republic and the International Brigades as examples of racial integration and progressivism. If the US doctor on the boat to Europe really refused to share a meal with Kea, it is no wonder the anecdote was excised from the story. A similar logic could explain why the pamphlet doesn’t mention Kea’s marriage to O’Reilly. However much the very relationship symbolized integration, for some audiences in the US it was thought a bit too advanced. “Kea was … discouraged from talking about her marriage (with a warning that it wouldn’t prove popular with black or white audiences),” Donlon writes, “an instruction she fiercely protested.” A further complication was Kea’s battlefield romance with, or possibly marriage to, Oliver Law, the Black commander of the Lincoln Batallion who was killed at the battle of Brunete—a story first reported in the New York Amsterdam News on September 26, 1937, and confirmed in James Neugass’ memoir War is Beautiful. (Donlon quotes Fredericka Martin to the same effect.)

Was Kea used by the organizations that sent her to Spain? Reid-Pharr suggests as much, writing that she was “a singularly effective tool in the leftist propaganda arsenal that had been established to support Republican Spain,” while the “leaders of the CPUSA and the editors of the Daily Worker wasted little time in utilizing her story to reiterate the poetics of internationalism underwriting the activities of the Spanish brigadiers.” But it’s just as plausible to argue that those organizations allowed Kea to educate and emancipate herself.

In the late 1960s, when filling out a questionnaire provided by Frances Patai, Kea indicated that she was a Catholic when she went to Spain. I think it’s more likely that she underwent a religious conversion later in life. We don’t know when exactly Kea (re)discovered her Catholic faith—none of the New York hospitals she worked at, for example, were Catholic. But once she had become a Catholic, she recast her life into a new narrative mold, one in which, even in Spain, she was an avid Bible reader who only wanted to do “Christ’s duty.” It was also a narrative that allowed her story to be told, proudly, in a United States in the grips of the Cold War. For Carmen Cañete, Kea simply adopted a collective voice, weaving “into her narration moments of the war that she did not witness but rather heard or read about from other brigadiers.” A final factor that cannot be discounted in Kea’s fabulist tendency is some form of mental decline. Kea is reported to have suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, but it’s not clear when that set in.

Kea’s shifting stories have posed problems for researchers. But even her biography, as far as we can reconstruct it from the historical record, does not easily fit into any of the available molds for telling the story of the American volunteers in Spain. For those of us who wish to portray the “Lincolns” as brave, antifascist internationalists whose lives are examples of progressive commitment—and whose role is scandalously under-exposed in mainstream US history—Kea’s religious take on her Spanish experience causes discomfort. But nor is her story any easier to accommodate for those who prefer to portray the US volunteers as Communist dupes who, as President Ronald Reagan suggested in 1984, fought “on the wrong side.”

When Salaria Kea died, in May 1990, at age 79, she’d been mentally gone for several years. This is perhaps why her grave, at Glendale Cemetery in Akron, misstates her year of birth as 1913, while the cemetery record and the newspaper obituary misreport her age at death to have been 73. But Akron has not forgotten her: for the past 30 years, the Historical Society has featured Kea in its city tours as a prominent member of the African American community. Unfortunately, there is no plaque in her memory at Harlem Hospital, where she first discovered the power of collective action.

A German version of this essay came out in Austria as “Heldin mit Widersprüchen: Salaria Kea,” in Tagebuch no. 8 (2022), pp. 30-39.

References

Cañete-Quesada, Carmen. “Salaria Kea and the Spanish Civil War: Memoirs of A Negro Nurse in Republican Spain.” Black USA and Spain: Shared Memories in the 20th Century. Ed. Rosalía Cornejo-Polar. Routledge, 2019.

Donlon, Anne. “Thyra Edwards’s Spanish Civil War Scrapbook: Black Internationalist Writing.” To Turn the Whole World Over: Black Women and Internationalism. Ed. Keisha N. Blain and Tiffany M. Gill. University of Illinois Press, 2019.

[Edwards, Thyra.] A Negro Nurse in Republican Spain. The Negro Committee to Aid Spain, 1938. Republished in 1977 by the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, Bay Area Post.

Everly, Kathryn. “Intersectional Silencing in the Archive: Salaria Kea and The Spanish Civil War.” Hispanic Studies Review 6.1 (2022).

Naison, Mark. Communists in Harlem during the Depression. University of Illinois Press, 1983.

Reid-Pharr, Robert F. Archives of Flesh. African America, Spain, and Post-Humanist Critique. NYU Press, 2016.

Sharpe, Emily Robins. Mosaic Fictions: Writing Identity in the Spanish Civil War. University of Toronto Press, 2020.

Wetherby, Aelwyn. Private Aid, Political Activism: American Medical Relief to Spain and China, 1936-1949. University of Missouri Press, 2017.