Who Was “John Sherman” of the American Medical Bureau?

A Spy in the Footnotes: In Search of John Sherman

By David Chambers

There was his name in the very first footnote of Eric R. Smith’s 2013 book American Relief Aid and the Spanish Civil War: John Sherman, working for the Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy. A few pages later, the notes mention a Jack Sherman. In all, John Sherman appears three times in Smith’s notes, Jack Sherman 11 times, and just “Sherman” 47 times. Curiously, his name appears not once in the book’s main text.

Note 1 with “John Sherman” in Eric R. Smith’s 2013 book American Relief Aid and the Spanish Civil War.

The name caught my eye because I am all but certain that the Jack or John Sherman who lurked in these footnotes was in fact John Loomis Sherman, three-time comrade-in-arms of Whittaker Chambers, my grandfather. For younger readers, ex-Soviet spy Chambers (in)famously testified to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) about members of a Soviet spy ring in Washington that included Alger Hiss, resulting in the Hiss(-Chambers) Case. As the case unfolded, Hiss found himself indicted on two counts of perjury in December 1948… Richard Nixon rose to fame thanks to the Hiss Case… And Joseph McCarthy cited the Hiss Case in his first anti-communist speech.

Chambers has much to say about Sherman in his 1952 memoir Witness. Sherman worked with him at the Daily Worker, newspaper of the CPUSA. He recommended and trained Chambers for underground work. He operated a spy ring with him. Curiously, right when John Loomis Sherman exits (1936) from the pages of Witness, a John Sherman surfaces (1936) at the Medical Bureau and North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy (MBNAC).

The research I present here suggests that these Shermans may well be one and the same person. But I’m not one hundred percent sure. And that’s where you, readers of The Volunteer, come in. In what follows, I will tell Sherman’s tale briefly and close with some questions. I hope you may have answers to share with me.

Sherman is important to me as the person most responsible for the spy history of our entire family. Had Sherman not earmarked Chambers for the Soviet underground, what else might have happened to my grandfather? What might all our lives have been like without the Hiss Case? (As you will see, the Hiss Case certainly affected John Loomis Sherman’s life.)

Sherman is just as important to help trace convolutions in Soviet intelligence before the Great Purge (1936-8). Specifically, fleshing out Sherman’s story should help carry on the unfinished work of Raymond W. Leonard (1959-2008). In his 1999 book Secret Soldiers of the Revolution: Soviet Military Intelligence, 1918-1933 (1999), Leonard traced crisscrossing, concurrent histories of the Cheka (NKVD, KGB), COMINTERN’s International Liaison Office (or OMS, long defunct), and Fourth Department of the Red Army (Soviet Military Intelligence, or GRU). I plan to continue his work for 1933-8. That period overlaps with my grandfather’s time in the Soviet underground—and the Spanish Civil War.

Further, if Sherman got involved in the Spanish Civil War effort, how many other Soviet spies (former or current) did? Known are Soviet spies like Ignace Reiss and Alexander Orlov. (See some of my initial findings about Soviet spy networks in a C-SPAN video.) If Sherman was an ex-Soviet spy, lurking unknown until now in the footnotes of the Spanish Civil War, what other Soviet spies—and Soviet ex-spies—may still lurk undetected?

Here follows the Sherman story I have researched so far.

John Sherman was born on October 19, 1895, in Fairfield, New York, near Utica. A census report from 1910 lists feedstore merchant David Sherman and wife Esther, born in the Russian Empire, Yiddish-speaking, who had arrived in 1895, were still alien, and lived at 12 Washington Street, Utica. They had several children, the eldest of whom was Jake (John). Sherman’s sister later told FBI agents that her parents were Lithuanian Jews. Sherman himself said he attended Syracuse University. (The university has found no record of a John Sherman, or Schermann, a common spelling of the name among Lithuanian Jews.)

In 1949, Whitaker Chambers testified about Sherman to a grand jury:

I understand that he had been a seaman, a sailor on a destroyer during the First World War and that the boat had docked in Arkhangelsk or Murmansk when we were aiding one of the White generals in the north, and while Sherman was there he was first indoctrinated with the Communist idea and when he came back here he joined the Communist Party and had some part in organizing the subway strike here in 1920 in New York City.

Indeed, in 1918-19 during the Allied Intervention into the USSR, the US Army send a Polar Bear Expedition to Murmansk, supported by the US Navy’s USS Olympia. Several dozen US sailors helped Russian sailors operate captured Russian destroyers for half a year. Some US sailors stayed behind when the USS Olympia left. One historian adds that the “most politically conscious elements in the Murmansk population in 1917 were the sailors and railroad workers.”

Is Chambers’ account of Sherman’s sailor days accurate? Possibly. As a Lithuanian Jew, Sherman may have spoken Russian as well as Yiddish. He may have been one of the US sailors who worked side-by-side with (Bolshevik) Russian sailors. They may have indoctrinated him in communism. And he may have been one of the US sailors who chose to stay behind.

A marriage certificate shows that on April 20, 1925, Sherman married Alma D. Loomis. He took her maiden name as his middle name. Alma, born August 9, 1895, in Syracuse, NY, was a piano teacher and graduate of the Institute of Music and Arts in New York. Another record shows a daughter Joan, born around 1932.

According to Witness, in 1927, when Chambers joined the staff of the Daily Worker, Sherman was already there. He was a “mysterious… a sturdy, bald Communist with a plain, pleasant face.” Sherman was going by the name Robert Mitchell. Along with Earl Browder and others, his primary job was labor agitation, or AgitProp—in his case, secretly organizing subway workers. AgitProp followed a two-step process: recruit and organize workers to foment strikes and then write up efforts in the DW.

In Witness, Chambers related that he and Sherman both loathed intra-Party factionalism. After they became friends, Sherman revealed his real name. Chambers called him “the first man I had met in the party of whom I felt unqualifiedly: he is a revolutionist.” During a reorganization of the CPUSA in 1929, Stalin promoted William Z. Foster over James P. Cannon and Jay Lovestone, while members of their defeated factions found themselves expelled. At the Daily Worker, Sherman felt the axe early. When he refused to denounce Lovestone, he was expelled—and disappeared.

Is Chambers’ account of Sherman’s role at the Daily Worker accurate? Yes. DW digital archives at the Library of Congress, Marxists.org, and Archive.org provide corroboration. Robert Mitchell appears as a byline on nearly 50 articles in 1927-28. The newspaper also makes 20 mentions of speeches or lectures by Robert Mitchell, almost all about “traction” (subway) workers. A meeting notice of Agitprop directors featured Robert Mitchell as principal speaker, i.e., Sherman was an AgitProp expert. Sherman’s articles stop appearing in February 1928, more than a year ahead of Jay Lovestone’s expulsion from the CPUSA (announced in the DW on June 27, 1929).

In 1932 and by then managing editor of the New Masses, Chambers continues in Witness, he received a summons. It came from Max Bedacht, president of the International Workers Order. It ordered him to drop all open associations with the Party and engage with “special institutions” in “underground work.” The next day, Bedacht walked Chambers over to a meeting in a Union Square subway station. There, Sherman—now Don—was waiting. Sherman, Chambers learned, had recommended him for the underground. Sherman trained him. Then he placed him in a first spy network (“apparatus” in Witness) called The Gallery. Sherman left to set up another in California.

Around 1934, Chambers continues in Witness, he received orders to set up a new apparatus in London. Soon after, Sherman came to him for help in setting up another in Tokyo. They pooled resources and recruited help from literary agent Maxim Lieber. The three set up the American Feature Writers Syndicate as a subsidiary to Lieber’s agency. Chambers was to go to London to open a satellite office of Lieber’s agency (an order later rescinded). Sherman went to Tokyo to operate the syndicate. In February 1935, Sherman hired Barbara Wertheim (the future Barbara Tuchman, historian and author of The Guns of August) in Tokyo to rewrite stories for the syndicate. In June 1935, Sherman had already left Tokyo when he wrote Tuchman, asking her to close out his office. (During the Hiss Case, Tuchman showed Sherman’s letter to the FBI.)

Soon after Tokyo, Chambers continues in Witness, Sherman received a summons to Moscow. He soon wound up in a Soviet prison; the Great Purge had started. Feigning illness, Sherman convinced the authorities to release him and send him to London on a new assignment. Instead, he fled to the States. He begged help from Chambers and Lieber. He urged them to leave the underground. Chambers later wrote: “His one desire was to return to the open Communist Party.” Chambers agreed to help. He prevaricated with Soviet bosses. This gave Sherman time to flee with his family. Sherman arrived in Los Angeles and rejoined the open Party.

Exit Sherman from Witness.

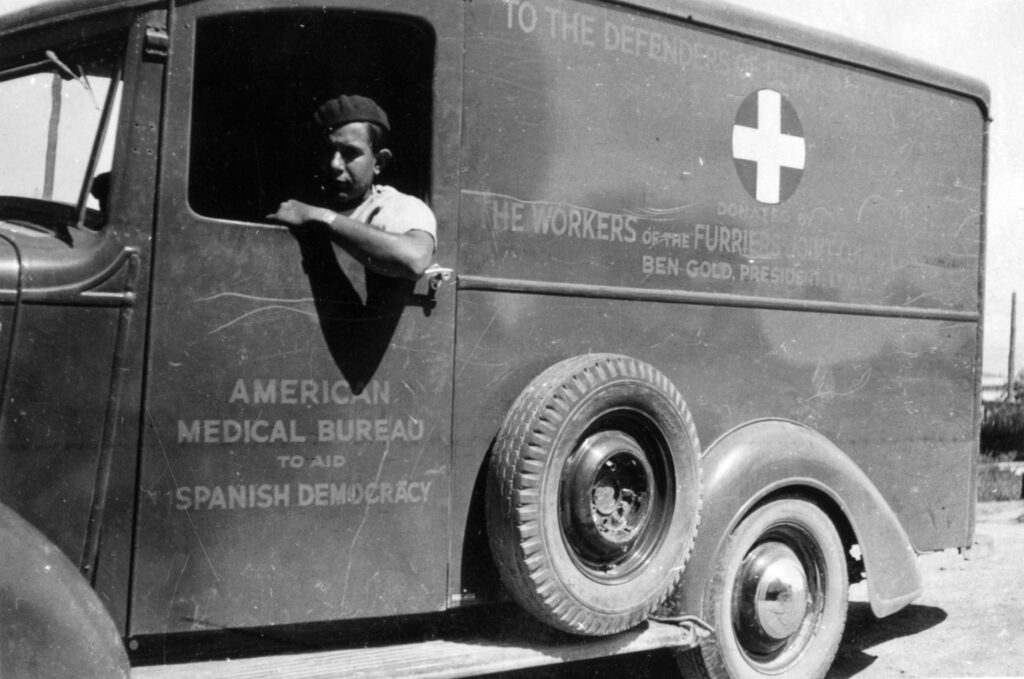

Around the same time, in 1936, Sherman started supporting the Spanish Republic in its struggle against fascism. By October, a John Sherman—likely the same person, as we have seen—was working for the North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy (NAC), serving as organizing secretary under Reverend Herman F. Reissig, executive secretary. Their titles suggest Reissig was the figurehead and Sherman the doer. By January 1938, the NAC merged with the Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy (MB) as the Medical Bureau and North American Committee (MBNAC).

By year-end 1938, the Spanish Civil War was all but lost, and in April 1939 MBNAC merged into the Spanish Refugee Relief Committee (SRRC). American Relief Aid and the Spanish Civil War mentions that Varian Fry served as MBNAC publicist. During WWII, Fry ran the Emergency Rescue Committee (now IRC) that saved Hannah Arendt, Marc Chagall, and Anna Seghers among others. The book does not mention Noel Field, a League of Nations representative and American NKVD agent whom Alger Hiss (a GRU agent) tried to recruit (according to NKVD agent Hede Massing). Field worked for Fry’s WWII organization in the 1940s, fled the US after the Hiss Case started, and wound up in a Hungarian prison in the 1950s, where he named Hiss.

NAC and MBNAC correspondence to, from, or about Sherman ranges from June 17, 1936, to February 20, 1940. The organization’s letterhead during this period includes Sherman’s name. Letters concern everyday efforts but no personal details. After the war ended in 1939, Sherman continued working in support of Spanish Republican refugees. The correspondence that mentions his name ends shortly after an FBI raid on VALB headquarters.

From Eric R. Smith’s research notes and book American Relief Aid and the Spanish Civil War, Sherman traveled all over the US to organize support for the Spanish Republic. Smith’s research notes show that Sherman was in touch with the International Workers Order (IWO) and its president Max Bedacht. This connection strongly supports the argument that the John Sherman of MBNAC was the John Loomis Sherman known to Chambers.

Given his AgitProp expertise, Sherman likely organized or wrote many of MBNAC’s publications, such as the 1939 Spain Fights On! According to a 1949 FBI memo, during his time with MBNAC, Sherman lectured on topics like America and the Next War, Current World Affairs, War, and Vital Issues of the Day. He may have recruited help from other CP organizers. Take Roy Hudson, CP executive in charge of unions: he wrote an AgitProp pamphlet Shipowners Plot Against Spanish Democracy in 1936 (online at Spanishky.dk)— “AgitProp” if only because it ends by urging “MARITIME WORKERS! ACT!”

The 1940s left little record for the FBI about Sherman himself. Alma Loomis left a medical trail at Rancho Los Amigos hospital (still thriving) in Los Angeles, where she stayed for months at a time. She died there on January 11, 1946. Her ailments suggest rheumatic fever as a child. A second marriage certificate shows that on June 7,1946, a 45-year-old Sherman remarried a 32-year-old, California-born Margaret Emily Herrick of Vista, CA. Like Alma, Margaret worked in music and registered a music copyright on October 15, 1945.

Chambers worked at TIME magazine from 1939 onwards. In late July 1948, two congressional committees had American ex-Soviet spy Elizabeth Bentley testify about communist infiltration in the US government. One of them, HUAC, subpoenaed Chambers to corroborate Bentley’s testimony on August 3, 1948, the start of the Hiss Case. Months later, Chambers mentioned Sherman (including the excerpt above) before a grand jury.

The first trial of Alger Hiss ended in a hung jury on July 7, 1949. DOJ officials asked the FBI to investigate Sherman to verify whether Alger Hiss and wife Priscilla were present on a day when Sherman visited Chambers in Baltimore. Instead, the FBI found little about him. Sherman himself claimed immunity due to a grand jury in Los Angeles. On January 21, 1950, a jury convicted Hiss on both counts of perjury. Soon, Sherman appeared under subpoena before HUAC.

On February 27, 1950, Sherman related his background and status: “jobless teacher” (as a Washington Post headline dubbed him) in Los Angeles. He told HUAC, as he had told the FBI, he could not answer questions, as he was sworn to secrecy by a Los Angeles grand jury. HUAC pressed him with questions; Sherman mostly pled the Fifth. Stymied, the chairman demanded answers. Sherman said he feared a “definite frame-up.” HUAC’s chair sagely opined, “No man can be guilty of perjury if he testifies the truth.” “Provided,” Sherman retorted, “there is not false evidence against him.”

On March 1, 1950, testimony resumed, HUAC asking questions, Sherman mostly pleading the Fifth. Stymied again, HUAC’s chair again attacked his immunity: “No Federal grand jury or State grand jury has any authority in law to gag anybody from testifying to the truth before any legislative committee.” Would the committee grant him immunity? “Certainly!” said the chair. Sherman retorted, “It is my understanding that, since 1892, Congress has not had that authority.”

Once HUAC asked, “In 1939, were you employed as organizational secretary of the Medical Bureau and North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy? Or the United American Spanish Aid Committee [a precursor to the JAFRC]?” Again, Sherman pled the Fifth; HUAC did not ask again.

Before leaving, Sherman lambasted HUAC. They had destroyed the reputation of “one fine American” (Hiss) based on the “frame-up of a disordered mind” (Chambers’). Further, as noted in Witness, Sherman tweaked HUAC noses by claiming Hiss “would not know me from Adam.” (Chambers had told investigators that Sherman used the name Adam when meeting Hiss in 1934.) The Adam reference went unnoticed by HUAC.

Newspapers nationwide, large and small, covered Sherman’s HUAC testimony. Yet the rest of the 1950s left little record of Sherman. His name appeared occasionally in classified government report: there was no new, significant information.

On March 25, 1962, John Loomis Sherman died age 66 of spleen cancer at Park View Hospital in Los Angeles. The death certificate shows him as American, born October 19, 1895, father and mother unknown, WWI veteran, survived by wife Margaret Sherman, and last living in Hollywood. Evergreen Cemetery in Boyle Heights confirmed his cremation to me on the phone.

End of story? Not quite. A John Sherman appears as the author of a short story published in Jewish Currents. (The story reads as a reflection by its narrator, wondering how his dying radical father married his late religious mother.) The magazine’s short bio on the author reads:

John Sherman of Berkeley, Calif., a new contributor, was one of the founders of Local 1199 of what is now the National Union of Hospital and Health Care Employees, and editor of 1199 News for several years in the 40’s and 50’s. Before then he had been national organizational secretary of the Medical Bureau and North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy (1937-40) and NYC Secretary of the Jewish People’s Committee early in the ’40’s.

It seems plausible that John Loomis Sherman helped Local 1199 (founded in 1932, now 1199SEIU), as he had helped MBNAC. It also seems plausible that Sherman helped the Jewish People’s Committee (for United Action against Fascism and Anti-Semitism). There is only one problem: the Jewish Currents issue date is April 1980, 18 years after John Loomis Sherman’s certified death.

Of course, the author of the story in JC could be a different John Sherman. The lives of two John Shermans could have overlapped by several decades. The lives of author Marguerite Young (1908-1995) and Daily Worker journalist Marguerite Young (1905-1995) overlapped entirely but for three years. The Sherman doubles might share interest in labor organizing, too.

But I think it more likely that Sherman faked his death. Outlandish?

Consider that his death certificate lists “frame maker” as his last occupation—with “frame manufacturing” listed as his job since the Hiss Case started. Three times during his 1950 testimony before HUAC, Sherman had mentioned a “frame-up.” Was Sherman having another laugh at the feds, like he did during HUAC hearings? The death certificate reframes John Loomis Sherman as dead. Thereafter, he could revert to a simpler, harder-to-trace John Sherman. After 18 years, he could test the waters by publishing a story as John Sherman to see whether he would attract (FBI) attention.

Consider too that, while the piece reads like a memoir, JC calls it a story. Was Sherman also challenging what makes a story true or false (frame-up)?

Lastly, did he intend the 1980 byline as a clue for later historians?

Given Sherman’s careful, finessed replies during testimony (without legal counsel), I would say yes to all the above.

Here ends a short, still incomplete version of the Sherman story so far.

I would be very grateful if any of you could email me answers to these questions:

- Do you know of any members of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade who served earlier at Murmansk as part of the Allied Intervention 1918-20?

- Do you have any further information about a Jack or John Sherman who worked at the Medical Bureau or North American Committee?

- Do any of you know whether the John Sherman who published a story in Jewish Currents was the same person as John Loomis Sherman, or otherwise what ever happened to John Sherman of Berkeley, CA, who worked at MBNAC, Local 1199, and the Jewish People’s Committee?

I would particularly love to hear from Sherman’s descendants.

David Chambers is an independent historian whose work focuses on Soviet intelligence in the USA from the 1920s through the ‘40s. He holds an MA from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service and BA from the University of Virginia. This article uses research contributed by Eric R. Smith, for which the author is most grateful.

A Note on John Loomis Sherman

By Daniel Czitrom

David Chambers asks us to consider the possible links between his grandfather, Whittaker Chambers, John Loomis Sherman, and various American organizations devoted to aiding the Spanish Republic during the 1930s. He has long been interested in researching all aspects of his grandfather’s life and influence via his “official” website, whittakerchambers.org. Both Chambers and Sherman wrote for the Daily Worker in the 1920s, while both were open members of the Communist Party. Both men left the DW in 1929, after the purge of the “Lovestoneite” faction of the CP, with which both men had identified. Then, in the early 1930s, Sherman re-emerged and evidently recruited Chambers for “instruction in underground organizational techniques,” as Chambers claimed in his memoir Witness. Sherman was involved in trying to set up espionage networks in London and Tokyo, but neither man had much success in the spying business. After a 1937 visit to Moscow, shaken by news of Stalin’s purge trials and fearing for his life, Sherman somehow convinced the Russians to let him go, and he returned to America, where in Los Angeles he once again engaged in open Communist Party work.

David Chambers wonders whether John Loomis Sherman was the same John Sherman who worked first for the North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy and the later umbrella group, Medical Bureau and North American Committee (MBNAC). It’s certainly possible, perhaps even likely. He further asks: “If Sherman got involved in the Spanish Civil War effort, how many other Soviet spies (former or current) did…what other Soviet spies –and Soviet ex-spies—may still lurk undetected?”

There are two problems here. First, Sherman was no longer involved with Soviet espionage but rather living as an open member of the CPUSA. More importantly, David Chambers may be exaggerating Sherman’s importance. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent opening up of long-closed archives have produced a stream of new scholarship examining Russian spy networks and their influence in the US. The prominent historians Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes have published several books on the topic, including The Soviet World of American Communism; The Secret World of American Communism; and Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America. Neither John Sherman nor his various aliases receives a single mention in their work. Nor does Sam Tanenhaus’ biography, Whittaker Chambers, add anything new about Sherman.

The strangest part of David Chambers’s essay is his contention that John Loomis Sherman faked his own death in 1962. Did Sherman compose his own death certificate (viewable online)? Was there a conspiracy possibly involving Sherman’s wife, the doctor who signed the death certificate, Park View Hospital, and even the Evergreen Cemetery, which confirmed his cremation? Highly unlikely, it would seem. Was the John Sherman who published the story “The Match” in a 1980 issue of Jewish Currents the same guy? He would have been 85 years old by then. What to make of the biographical note included with the story? Hard to tell. “The Match” might have been written many years earlier, and perhaps submitted by one of Sherman’s relatives or friends. Or it may have been another John Sherman entirely.

No one would be interested in John Loomis Sherman save for his connection to Whittaker Chambers. One hopes that David Chambers can find answers to the questions he poses at the end of his piece. But overall, John Loomis Sherman strikes me as a shadowy minor figure, a small fish in a very large and murky pond.

Daniel Czitrom is Emeritus Chair of the ALBA Board of Governors