The “Lying Press”: (Mis)Reporting on the Spanish Civil War

A dossier on the lies and deceptions surrounding the Spanish Civil War could fill a library, and it’s become commonplace to underscore the mendacity of the journalists reporting on events in Spain. Still, a careful analysis of the way that major international news agencies covered the war tells a more complicated story.

Not so long ago, the 1930s—“a low dishonest decade,” in W.H. Auden’s words —seemed a remote and unique seedbed of media deception. But today, as the world is entering a post-truth dystopia, the challenges of that time appear not quite as different from our present as they used to.

On 18 November 1936, while Madrid was being relentlessly bombed from the air, France was gripped by a “fake news” controversy. That day, the Communist newspaper L’Humanité devoted its front page to the far-right defamations that had driven a French government minister, Roger Salengro, to suicide. In the months that followed, the newspaper’s dogged campaign against “the lying press, the murderous press” would also become the leitmotif of its Spanish Civil War coverage. Since then, it’s become commonplace to underscore the mendacity of the journalists reporting on Spain. George Orwell famously, in “Looking Back on the Spanish War” (written in 1942), spoke of “newspaper reports which did not bear any relation to the facts, not even the relationship which is implied in an ordinary lie.”

It’s true that a dossier on the lies and deceptions surrounding the Spanish Civil War could fill a library. The US historian Herbert Southworth magisterially dismantled the persistent falsehoods about the destruction of Guernica, along with other narratives promoted by Franco’s supporters. Journalistic reporting was inevitably shaped by military rationale. Besides exercising censorship on domestic and foreign journalists, the Republican and Francoist authorities both invested heavily in press and propaganda initiatives within Spain and for an international audience. Their incessant flow of information—or disinformation—included dubious official handouts or triumphant radio broadcasts intended to fire up supporters and sap morale in enemy territory. For example, in early August 1936, the rebel-run Radio Seville claimed that General Mola’s forces had reached the outskirts of Madrid (they were nowhere near), where, supposedly, white sheets were hanging from buildings. Although the claim was entirely baseless, it still found its way into the international press.

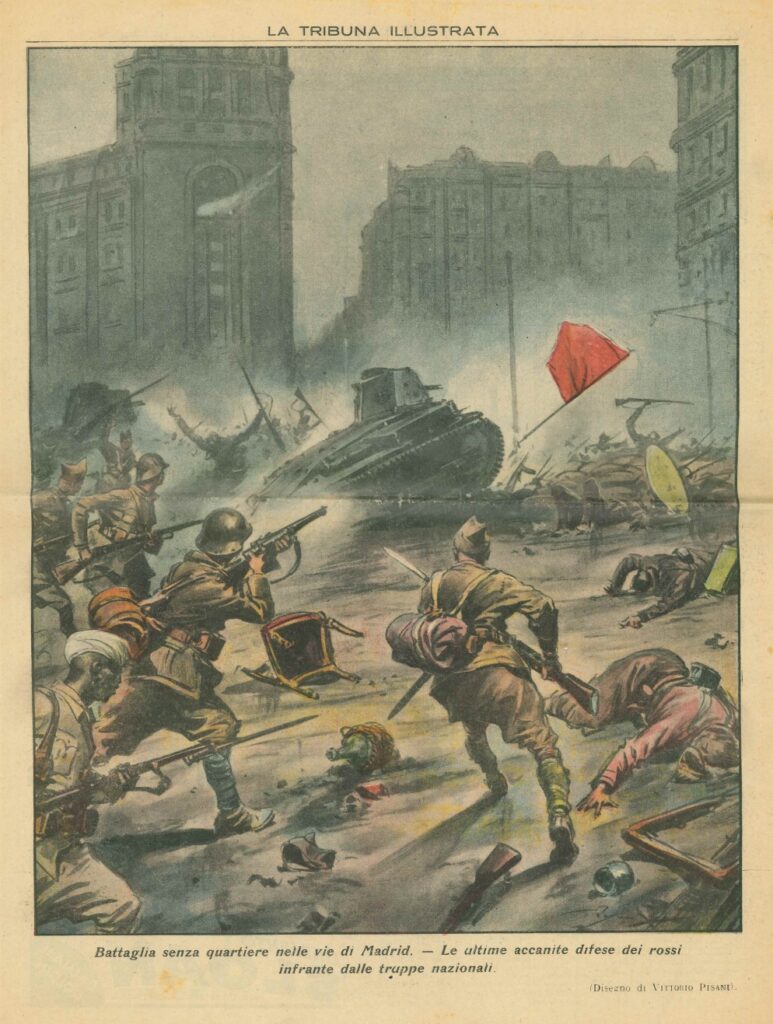

Italian review imagining Franco’s troops advancing near Hotel Florida in Madrid. La tribuna illustrata, Rome, 22 November 1936 (author’s collection).

The Spanish authorities were not the only ones engaging in deception. In fact, official deceit was embodied in the very policy of Non-Intervention. How could news organizations in Britain and France report serenely on German and Italian military involvement when their own governments were so equivocal when it came to Spain? Newspaper reports on the war referred coyly to “enemy planes” instead of identifying them by nationality. In September 1936, when the London-based Reuters news agency checked with the British government about reporting on the Italian military participation in the Nationalist attack on Majorca, it was asked not to stir things up. Still, the Italian presence there turned into a persistent long-term problem with potential diplomatic repercussions.

Despite these efforts at containment, however, rolling press coverage, with its insatiable demand for news of all kinds, had its own dynamic, one that outside agencies struggled to control. Almost everywhere, the reading public was deeply invested in Spanish events. For some, Spain was a battlefield against fascism, for others, a crusade for Christian civilization. These emotional and political investments stoked intense press interest.

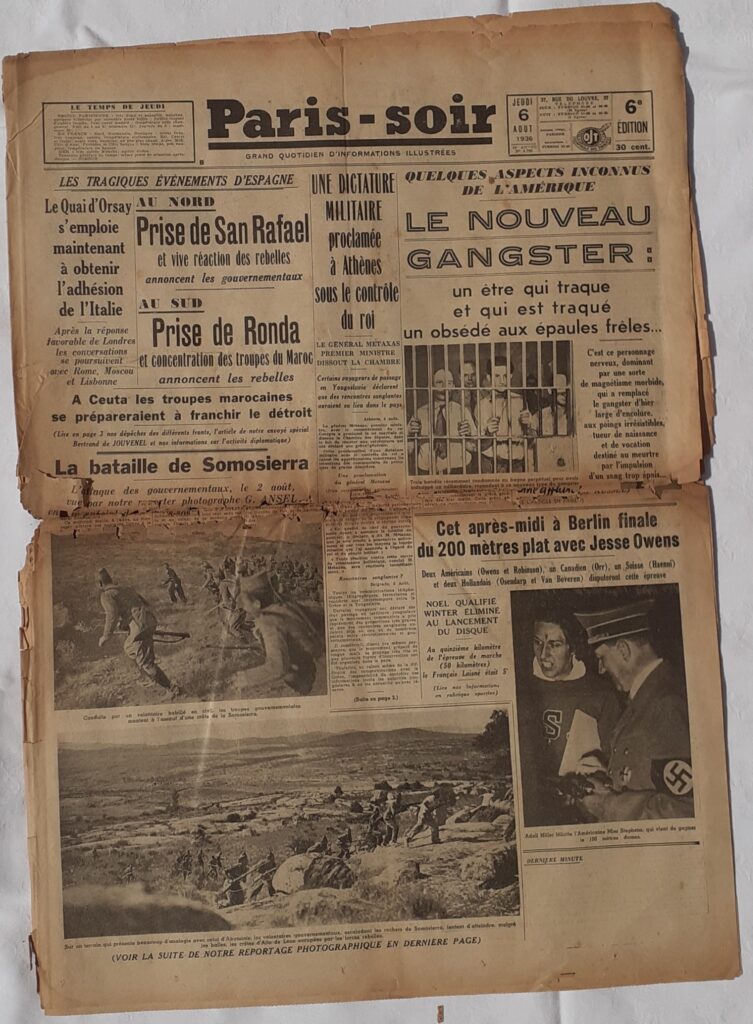

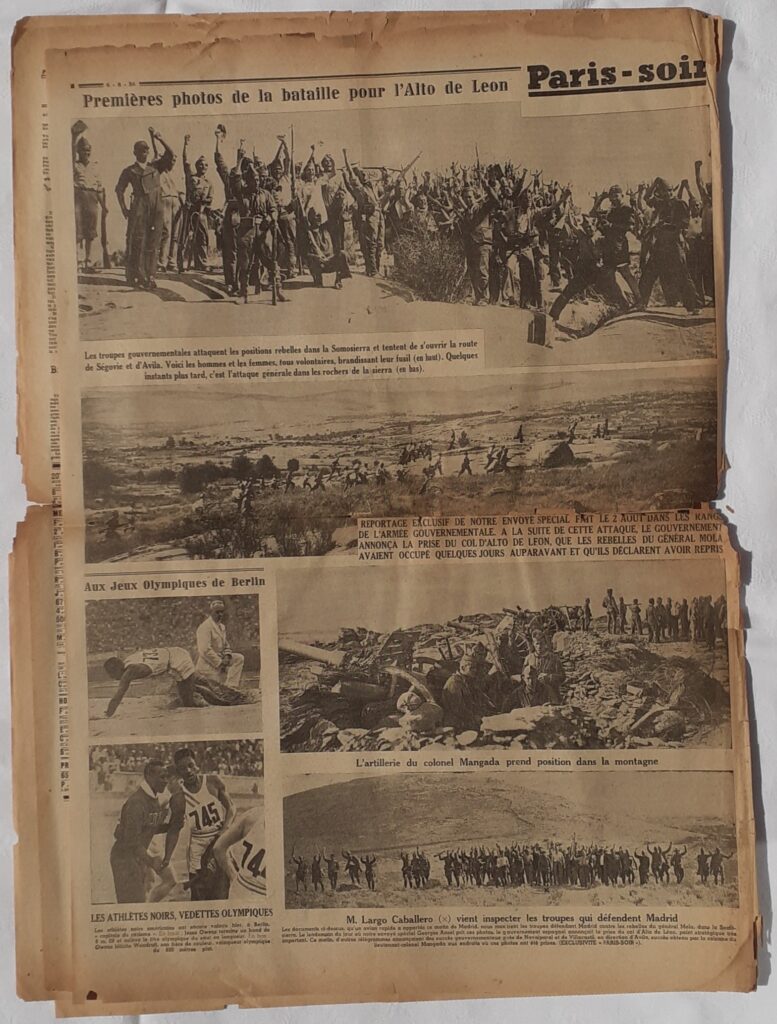

Paris-soir (6 Aug. 1936) presented Republican and Nationalist claims identically (“The taking of…”), showcasing new images (author’s collection).

In France and Britain, this was the heyday of the written press, with fifteen Paris newspapers reaching six-figure circulation figures, while two of them—and several London dailies—sold over a million copies a day. Many newspapers championed one side or the other, but the biggest trod carefully so as not to antagonize potential readers. Thus, mass-circulation French newspapers offered symmetrically balanced columns with contrasting versions: “Madrid claims…”, “Burgos claims…” This ostentatious equidistance was a powerful counterweight to overt political alignment elsewhere. The largest newspapers functioned like modern news aggregators, publishing an amalgam of texts derived from agency wires, radio broadcasts or official communiqués as well as their own correspondents. These items were often contradictory, while coherence was further sapped by the tardy transmission of images. Thus, the storming of the Montaña Barracks in Madrid took place on 20 July 1936 but the first dramatic photos reached the international press three to four days later, while coverage of the attempted insurrection in Barcelona followed a similar timeline. These were dramatic events, but readers could not follow them in real time.

Unlike much of the British press, the French newspapers offered front-page headline news, allowing us to measure in column inches the extraordinary impact of the Spanish Civil War between late July and early September 1936. Photojournalism had grown in importance in the 1930s, especially in mass-market newspapers whose front-page images and whole-page photographic spreads made this the ideal summer story, a human drama set in spectacular landscapes. Even for uncommitted readers, Spain offered the unhappy but gripping spectacle of the first large-scale conflict in Europe since the early 1920s. But coverage dipped from mid-September 1936, except for major events like Toledo, Madrid or Guernica. As war fatigue set in, the Paris-based Havas news agency reported in October 1937 that it had received complaints about the obscurity of military operations.

Only a select club of organizations had the resources and goodwill to maintain a daily information service in both Republican and Nationalist Spain. The main news providers were agencies like Havas (France), Reuters (Britain), or Associated Press and United Press (North America), along with some up-market and mass-circulation newspapers whose reporting was widely echoed elsewhere. Other newspapers drew on these sources, complementing them with contributions from one-off special correspondents or opinion columnists. Headline writers gave stories their distinctive flavor. In a competitive news environment, newspapers battled to be ahead of the curve, while in the more politicized dailies, they sold optimism by trumpeting “our” victories. In two important cases, the Alcázar of Toledo and Madrid, key calls were made at the head office, far from the battlefield.

Despite earlier press interest, the fate of the besieged rebels in the Alcázar of Toledo only turned into a massive news event in September 1936 because the Republican premier Largo Caballero resolved to achieve a very public, morale-boosting victory. On the 18th, the Alcázar was dynamited using explosives placed in underground tunnels: a spectacular explosion sent the southwest tower crashing down, releasing an immense column of fire and smoke. Fallen rubble provided the defenders with parapets they successfully defended, but this was not immediately apparent: numerous foreign newspapers announced that the Red Flag [sic] was flying over the ruins of the Alcázar. Many correspondents had filed broadly accurate dispatches, but the headline writers feared missing out on the big news. In contrast, the Francoist conquest of Toledo on 27–28 September was, from a journalistic viewpoint, a strictly behind-closed-doors affair as the Francoists ensured that correspondents only saw the fighting from a remote hillside. Many journalists could see evidence of large-scale killings after they entered Toledo, but these deaths were part of a non-event: there was no “Battle of Toledo” and no cause célèbre. The Francoist decision to turn the tap off at source can therefore be considered brutally effective. Franco only allowed carefully selected right-wing journalists to visit the Alcázar once the dust had settled.

All eyes turned to Madrid as Franco’s seemingly invincible forces advanced on the city; and on 8 November 1936 many newspapers wrongly announced his triumph. This press debacle owed much to the need to beat deadlines, but in France especially there was a split along ideological lines. For leftists, this was the world’s frontline resistance to international fascism, and it was unthinkable to bury that cause prematurely. None of the four biggest progressive newspapers in France did so. Rightist newspapers carried the headline “Franco’s Forces Have Entered Madrid”, as did the supposedly reliable Le Petit Parisien.

Too many journalists were in the wrong place, especially on the Nationalist side, where only a handful got anywhere near the frontline. According to L’Humanité, the accounts published by the grande presse were cooked up in Salamanca or Hendaye by correspondents like Le Matin’s, who wrote from his hotel room while listening to the radio. On the Republican side, many journalists had left for Valencia, and the voices of the well-informed ones in Madrid were drowned out. Thus, Henry Buckley’s accurate writing for the conservative Daily Telegraph had to compete for space against myriad unauthenticated texts. The Daily Express acknowledged that “the biggest barrage in the Spanish Civil War [was] squirted from fountain pens at headquarters”.

In terms of international impact, no news story matched the aerial bombardment of the Basque town of Guernica on 26 April 1937. But this was a different news event in Britain and France. Britain’s longtime fascination with the Basque Country—driven in part by the region’s economic relationship with England—meant that British-based journalists were already in Bilbao covering Franco’s naval blockade before they hastened to the bombed town. A remarkably “pure” news event then unfolded as flash cables and the first reports on the afternoon of April 27 were rapidly complemented by exceptionally complete dispatches on the 28th.

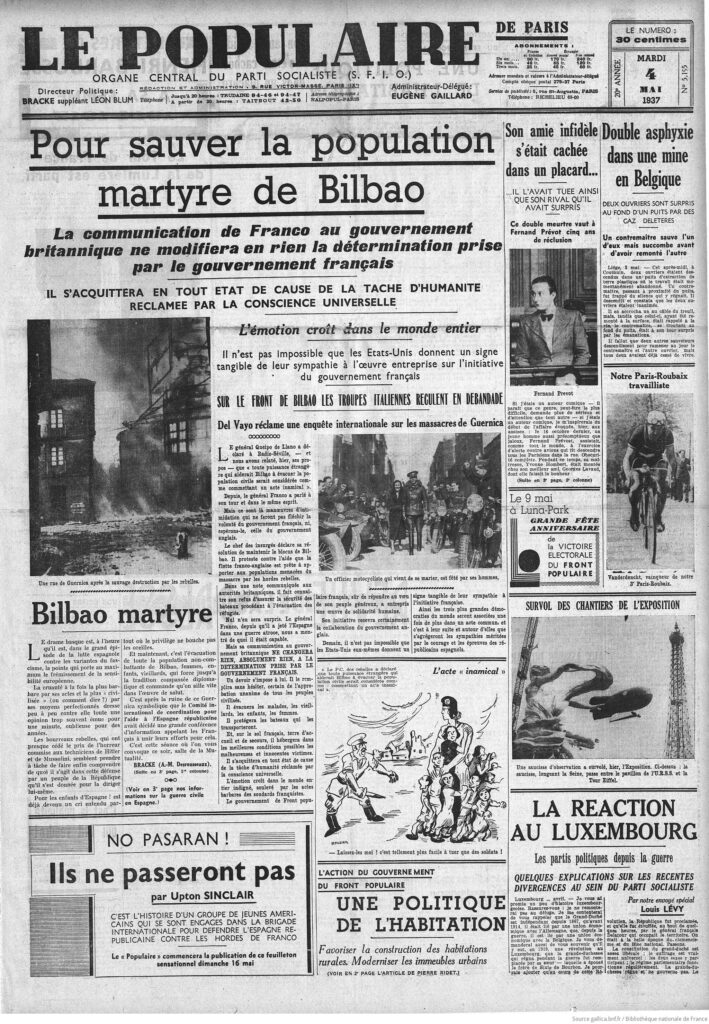

In contrast, French coverage was highly confused. Havas pressed its correspondent for the kind of material The Times had published. Ce Soir received a genuine report about the bombing of a completely different Basque village and then dressed it up as if it referred to Guernica. But there was no wall of silence: the event figured prominently in the biggest dailies. Other newspapers were more politicized in the run-up to the first International Workers’ Day to be celebrated under a Popular Front government (May 1, 1937). Left-wing French newspapers did not ignore Guernica, but they sought to create a broader anti-fascist narrative, shifting into campaigning mode on behalf of Bilbao, the next prospective “martyred” city.

After Guernica, the progressive French press turned to Bilbao. Le Populaire, 4 May 1937. Gallica, BNF.

Internationally, the combined work of a prestigious establishment newspaper, The Times (also the New York Times) and leading news agency, Reuters, were decisive in launching “Guernica”. And once a story had taken shape, it became difficult to reverse it. In May 1937, Francoist fabrications that Basque incendiaries had destroyed Guernica were reported only mutedly by the right-wing French press—surprising, considering their exceptionally privileged access to the Nationalist propaganda machine. In France, a comparable combination of a respected newspaper and news agency (Le Temps and Havas) had given credibility to reports of the mass killings at Badajoz in August 1936. It is telling that the Communist L’Humanité considered the testimony of liberal or conservative correspondents quite unassailable. On the bloody bombardments of Madrid of November 1936, it republished Louis Delaprée, who wrote for the conservative Paris-soir; for Guernica, it turned to George Steer of the London Times.

The heft of these news organizations created a bedrock of shared news that crossed international and ideological borders. In the Irish Free State, for example, all three major Dublin dailies used Reuters’ reporting of the destruction of Guernica in April 1937, even though their divergent sympathies were reflected in their headlines, presentation, and the inclusion of certain details. More surprisingly, even Moscow and Berlin drew from the same well. Nazi Germany had their own news agency, the Deutsches Nachrichtenbüro, but they kept half an eye on Britain. On 21 November 1936, for example, when the Daily Herald published a pathbreaking report on the “famous” International Brigades, the German press denounced the “regiment of Frenchmen” [sic] going to the “Bolshevist front in Spain”, specifically referencing the British press. Similarly, just before the fall of Toledo in late September 1936, the Moscow Daily News cited mainstream British news organizations like the Daily Telegraph and The Times for a claim that the government wanted to flood the Tagus Valley.

Essentially, in other words, a group of key news organizations were supplying the accepted “facts,” which could then be embroidered, trumpeted or ignored by other media. But limitations in geographical reach and the contingencies of reporting meant that only the stories they covered rapidly and in depth—the killings at Badajoz (but not elsewhere), the siege of Toledo (but not of Oviedo), the bombardment of Guernica (but not of Durango)—entered the “big narrative” of the Spanish Civil War.

What then of the “lying press”? L’Humanité relaunched its campaign against fake news in December 1936 and January 1937, when it denounced Paris-soir for eviscerating reporting of its own correspondent, Louis Delaprée, on the aerial bombardments of Madrid. In its campaign, L’Humanité went out of its way to contrast the “Big Truth”—the fact that Spanish women and children were dying—with the selective or incomplete coverage of events in Spain by the mainstream press.

For all L’Humanité’s partisanship, the paper had a point. In his charged descriptions of the effects of the Nationalist bombing campaign, Delaprée was less interested in factuality than in exploring an emotional truth, as he did when he wrote about a dying woman grasping her dead baby in a strangely illuminated night scene. (It may have been this emotional coverage of the Madrid bombings that sparked the inspiration for Picasso’s Guernica, as I have argued in these pages.)

Still, the bread-and-butter of press coverage was of a different order: When and where were the attacks taking place? What were the casualty figures? L’Humanité was tacitly admitting that the more banal missteps of French newspapers were not “lies” as such: news coverage is messy and accident-prone by nature. As the former correspondent in Madrid Sir Geoffrey Cox told me in 2005, the news, after all, is “the truth as you’ve established it by eleven o’clock that night.”

Martin Minchom, Ph.D, is an independent Madrid-based historian. This piece draws on his book The Spanish Civil War in the British and French Press: The Badajoz, Alcázar of Toledo, Madrid, and Guernica News Stories (Liverpool University Press, 2024).