“It Took Me Years to Understand My Work as Part of a Cultural Battle.” Roc Blackblock, Catalan Muralist

The Barcelona-born muralist Roc Blackblock, who started painting walls 25 years ago, takes his inspiration from photography to put the spotlight on historical struggles against fascism, for democracy, and for human rights as a way of intervening in the political present. “Having a good photograph to work from makes a huge difference.”

If you drive an hour and a half west from Barcelona until you reach the foot of the Prades mountains, you’ll find a nineteenth-century inn with a large, portico-lined patio that today is home to a youth hostel. It was here, on Tuesday, October 25, 1938, that Spanish Prime Minister Juan Negrín, flanked by Generals Rojo and Líster, gave a legendary farewell speech to the surviving members of the International Brigades, which had been demobilized on September 23. The iconic photographs of the event, by Robert Capa and Henry Buckley, show weary, unshaven, beret-wearing men who, visibly moved, lift their right fist to their temple in a last salute to the Spanish Republican leader.

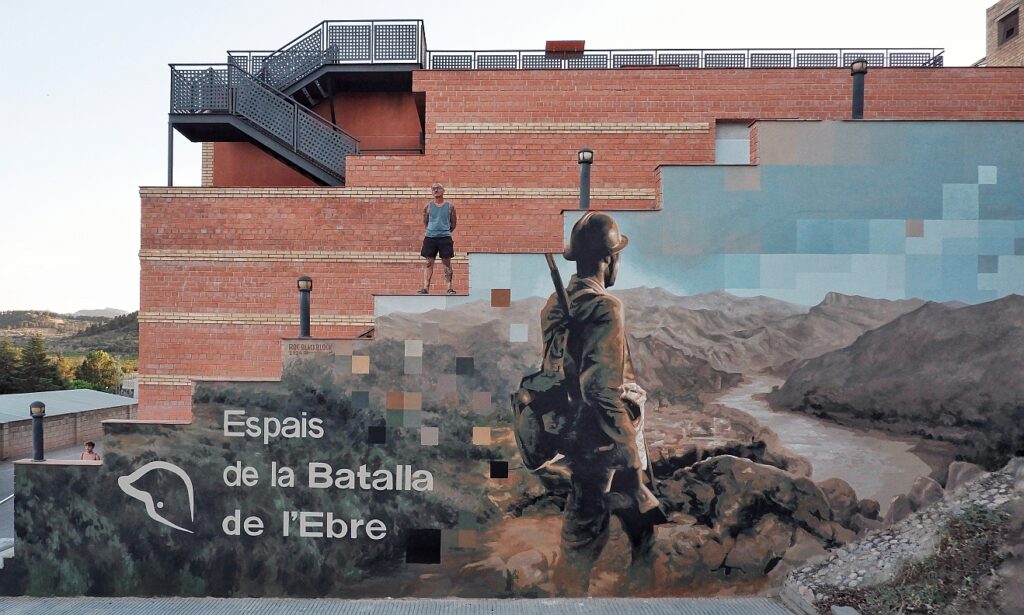

For today’s visitors to the inn, L’alberg l’Espluga de Francolí Xanascat, the historical connection is hard to miss. For the past three years, the building has featured a small museum dedicated to the International Brigades, sponsored by the Catalan government. And since 2023, one of the terracotta-colored exterior walls of the complex is covered with a large mural inspired by one of Capa’s close-up portraits of a brigadista.

Blackblock with his mural inspired by Antoni Campañà at the Fundación Anselmo Lorenzo (Madrid), Jan. 2025. Photo Rojo y Negro.

“When I spend so much time with a single image, something interesting happens,” the muralist, who signs his work Roc Blackblock, told me in February. “It’s not so much that I emotionally connect with the photographer, Robert Capa in this case. But I do end up feeling a strong bond with the person in the photograph. After all, I’m looking them in the eyes, touching their faces, for days on end. I felt something similar in January, when I painted a mural in Madrid inspired by one of Antoni Campañà’s iconic photographs from the early days of the war in Barcelona—the image of a miliciana on the Ramblas holding up an anarchist flag. She’s radiant, so full of joy. By now we know her name, Anita Garbín, and it turns out she was pregnant at the time. While working on the mural I couldn’t help wondering what she was going through when the picture was taken.”

“Having a good photograph to work from makes a huge difference,” Blackblock told me. “Want to hear a funny story? For the International Brigades mural at the Espluga inn, the initial idea was for me to use one of Henry Buckley’s images. That was relatively simple, because his photographs are held by a local Catalan archive and his granddaughter had very generously given us permission to use them. It made financial sense, too. Capa’s work is managed by Magnum, which means that the rights are quite expensive, and there was no room for anything like that in the project budget, which was financed by a tiny municipality. The problem was, though, that even though Buckley’s photographs are of great historical value, they don’t quite work as large reproductions. Capa’s images are much more powerful in that sense. So, in the end, I said: ‘Screw it, when am I ever going to get a chance to work with an image like this again?’ And I paid for the Capa rights with my own honorarium. It was worth it.”

The Capa mural is one of several tributes to the International Brigades that Roc Blackblock has been painting throughout Catalonia as part of a broader project titled Murs de Bitàcola, which roughly translates as Logbook Walls. The series, which so far comprises some forty murals, puts the spotlight on historical struggles against fascism, for democracy, and for human rights, always in connection with the political present. They include gripping images from the Civil War (various militiamen and -women; the bombings of Tortosa and Madrid; the massacre of refugees on the road from Málaga to Almería; the Republican exiles who left for Chile) and from the Francoist period (the struggle of the guerrilla or maquis; the execution of Salvador Puig Antich). But they also reference other historical episodes, from the pre-war rebellions by miners and peasants in Asturias (1934) and Extremadura (1936) to the international fight for women’s suffrage.

Roc Blackblock, who was born in Barcelona in 1975, has been active for about a quarter of a century. “I came up in the 1990s,” he told me, “when I joined the squatter movement and the insumisos or ‘insubordinates’ who refused not only the then-compulsory military service, but also the alternative service that was imposed on conscientious objectors. In high school, I’d studied graphic design, which I followed up with a two-year course in illustration. During that time, I met a grafitero who was part of the orthodox graffiti scene in Barcelona. It occurred to me to invite him to paint a wall in the social center where I lived, in a squatted former factory. He not only accepted the invitation and allowed me to help him with the project, but he also let me keep the leftover bottles of spray paint. That’s when I started doing political murals—I was an activist, after all. Although my connections came through the graffiti scene and I’ve always used spray paint, I never really got into graffiti proper. My inspiration came from the political murals from the 1980s, and ‘90s: against nuclear energy, in solidarity with Nicaragua, and so forth.”

What is your family background?

My mother’s parents were working-class migrants from Alicante. But since my father’s family belonged to the Catalan bourgeoisie, I grew up in a conservative, Catalan-nationalist, middle-class household. The fact that I could study graphic design at a prestigious private art school was, in a way, a sign of privilege.

How would you describe your own politics?

My politics were shaped by my years in the insumiso and squatter movements. At this point in my life, I guess I’m closest to anarcho-communism, or what in Spanish we call el comunismo libertario. Historically, I identify with the Barcelona of the 1936 social revolution. But that doesn’t mean I don’t have friends in the Communist party, or that I don’t respect the communists’ struggle against the dictatorship. I’m not sectarian.

You’re a professional artist and many of your murals are commissions. Do you ever feel tension between your activism and your professional career?

The balance has not always been easy to strike, although I have managed to find a way. You could say I always have one foot in political activism and one foot in the professional sphere. As a professional artist, I could have easily gone in a commercial direction and accepted commissions for mainstream music festivals, multinational corporate sponsorships, and so forth. In recent years, we’ve witnessed a massive absorption by the neoliberal market of counterculture, graffiti, and street art. Had I gone that route, then the tension would have quickly become unsustainable. In fact, over the years I’ve rejected certain projects for that reason. These days, though, my profile is relatively well defined. My commissions most often come from public institutions and city governments who know me as someone who works on topics related to historical memory and antifascism. I just came back from a week in Mallorca, for example, to do a mural on the mass graves of civil war victims there. That project was commissioned by the city government of Inca and the island’s historical memory association. On the other hand, if the Banco Santander were looking for a muralist, I’d not be the one they’d call. (Laughs.)

Are all your murals commissioned these days?

No, I continue to do projects on my own initiative—for example, the mural I did in Gijón last year to commemorate the ninetieth anniversary of the October Revolution in Asturias, or the one dedicated to Salvador Puig Antich, the young Catalan anarchist who was executed by the Franco regime in 1974. Those are projects I do as an activist, for free or at cost.

Some of the iconic photographs you incorporate into your murals, by Robert Capa, Agustí Centelles or Antoni Campañà, famously inspired poster and mural artists like Josep Renau or Pere Catala Pic during the years of the Second Republic and the war. Do you see yourself as part of that artistic tradition?

That’s a difficult question. Although I studied graphic design, I never really worked in that field—apart from making a living as a tattoo artist and illustrator for many years. It’s true that my education shapes how I see the world and represent it in my work. But if I’m honest, I’m hesitant to see myself as part of any artistic tradition. I much prefer to see myself as a worker, a communicator who uses a particular set of tools and who, over time, has developed a particular set of skills. If you look at the development of my technique, for example, there are changes that simply respond to phases in my life. When my first daughter was born, I started painting less to be able to spend more time at home, and after the birth of my second daughter, I stopped painting altogether for a couple of years, doing other work instead. When I eventually returned to doing murals, I began working with stencils, for the simple reason that it allowed me to do most of the preparation at home and spend less time on site. Even today, when I’m working, I don’t think in terms of inspiration or virtuosity. It’s much more mechanical: I’m putting in hours to get the job done. Just now, for the Mallorca job, I spent six days in a row working from seven in the morning till seven at night.

One way to see your murals is as bold interventions in public space. They call attention to themselves and interpellated viewers or passersby. Sometimes their message is quite explicit, sometimes not so much.

I go back and forth on that. It also depends on the commission. Some of my work leaves little to the imagination. But when I did the mural for the museum dedicated to the Battle of the Ebro, I used an image of a single soldier, seen from the back, overlooking the river, which is much more open to interpretation.

Spain today continues to be engaged in memory battles, with different groups proposing different ways to tell the story of the twentieth century. Do you see your work as contributing to that battle?

To be perfectly honest, it took me years to understand my own work in that way, as part of a battle for hegemony. I now realize I’d been instinctively engaged in that struggle from the beginning. On the other hand, I don’t control how people read my images or what happens to them over time. I once did a mural for a squatted social center depicting protestors running from the police. When the police evicted the squatters, there was a week of intense protests, after which the squatters retook the center. Ten years later, they are still there, and my mural has turned into an icon of resistance. But I had nothing to do with that.

Mallorca, where you just painted a mural, has been the site of one of those battles, as the regional government has been trying to dial back the memory law adopted several years ago, which among other things calls for a recognition of Franco’s victims.

Exactly. The regional government of the Balearic Islands is now controlled by the Partido Popular and the far-right party Vox. In June last year, as the parliament was debating repealing the memory law, the speaker of the parliament tore up a picture of Aurora Picornell, known as the Pasionaria of Mallorca. She was a young woman affiliated with the Communist Party who was disappeared and assassinated in January 1937, after Franco’s forces had quickly taken over Mallorca and turned it into an Italian military base. In fact, Picornell’s remains were only recently recovered from a mass grave. So, this is the context in which the progressive city government of Inca commissioned me to paint a mural to honor the victims of right-wing repression, which I was happy to do, of course.

You also did a mural to denounce the corruption of the former king, which caused a stir.

This was when the rapper Pablo Hásel was indicted for his lyrics, which simply stated the truth: that emeritus King Juan Carlos I is a thief. With a handful of fellow artists, we thought that situation warranted a response in defense of all of us who do creative work—although in practice we didn’t officially represent anyone. So, we painted a mural that simply confirmed what Hásel had said—Juan Carlos’s face with a label of “thief” on his forehead—in the same way that, when we were in the insumiso movement, we’d say: if you imprison folks for refusing to join the military, then I, too, will refuse to join. We did the Juan Carlos mural in a space where, in principle, painting is allowed as long as it doesn’t include hate speech or calls to violence. And yet, almost immediately, the police ordered it painted over. What happened, though, was that someone filmed the city crews doing that. And that video went viral, causing a huge scandal and all kinds of conspiracy theories. In other words, it became a textbook example of the Barbara Streisand effect! (Laughs.) The city apologized and asked me to restore the mural, which I did about a week later. A short time after, it was defaced with far-right slogans. In other words, the battle goes on.

Sebastiaan Faber serves on the ALBA Board and teaches at Oberlin College.