How I Found My Grandfather’s Play about the Lincoln Brigade

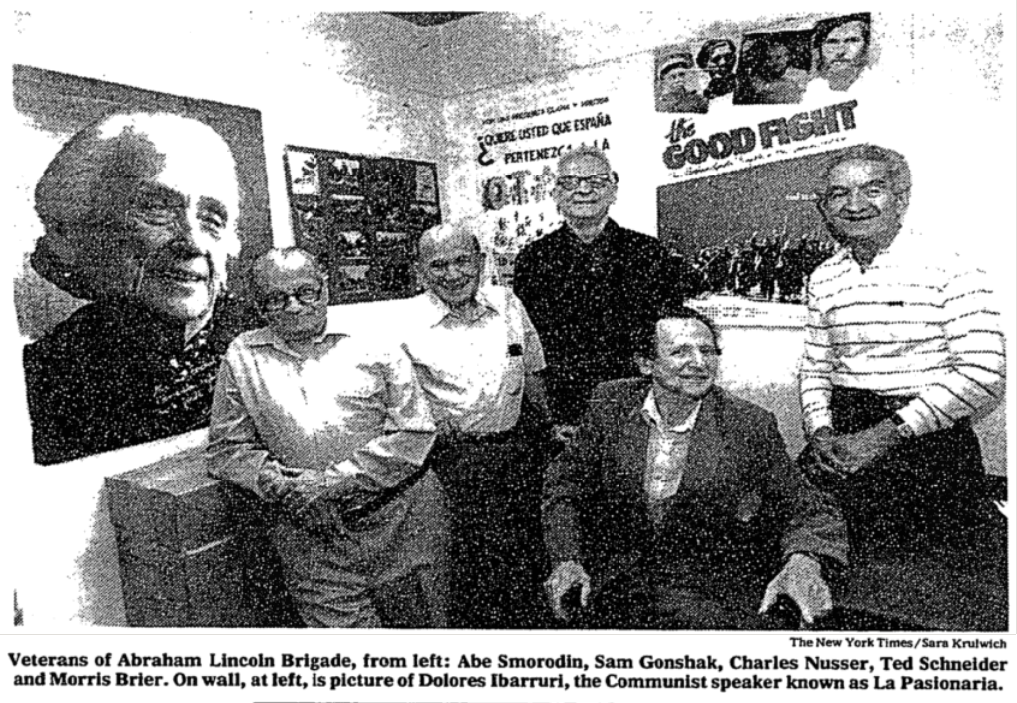

In the spring of 2024, while cleaning up an old family home, Kate Fogarty came across the typescript of a play about the Lincoln Brigade written by her grandfather, Charlie Nusser, who served in Spain from February to October 1937 and fought in the US Army during the Second World War. Ten months after Kate’s find, the play was performed in Spain.

The year 2024 began rough for my aunt Paulette. On a bitterly cold Saturday evening in January, her modest home in Chicago caught fire. She, her husband Anthony, and their dog made it out safely, but the following weeks were spent in a hotel and a rental home in the suburbs. Months later, on Good Friday, Uncle Tony passed away from a heart attack.

At Easter I caught a flight up to Chicago and Paulette and I went to work to get her affairs in order. She and my uncle owned a second home in upstate Illinois, a farmstead that his parents had built. Paulette mentioned that, after the fire, Tony had rescued some items from their Chicago home and moved them upstate. My aunt and I planned to spend a couple of days there to sort through it. We found the living room filled with small pieces of furniture and about eight heavy-duty black trash bags. Undaunted, we set to work. After about three hours, I came upon some DVDs of a recorded conversation between my grandfather, Charlie Nusser, a veteran of the Lincoln Brigade who had passed away in 1993, and his fellow Lincoln vet Steve Nelson. I also found a yellow folder containing a stack of papers that Paulette recognized as my grandfather’s. Some pages were written by hand, while others were typed, and a handful of pages looked to be more recently printed.

I asked my aunt if I could take the entire folder with me. At home, I began by scanning the newest-looking pages—which, miraculously, my aunt had printed from the computer that was later destroyed in the house fire—and converting them into Word. It appeared that the folder contained two separate texts. The first was a memoir called “Give me a Hero’s Welcome.” The other was a play titled “The Volunteers.”

My mother, Helen, was aware of her father’s memoir, but the existence of the play was news to her. Paulette, however, knew more. She now remembered that, at one point, a group in Chicago had been interested in producing it, but that grandpa and the producer decided it would prove too costly to put on. Looking back, I suspect Charlie was also quite ambivalent about his work. In a transcribed interview with Art Landis that Ray Hoff shared with me, and which likely was recorded in the 1960s, Charlie had said: “Spain is better left in the closet. I’d just as soon have people forget all about it.” I’m wondering now if, with that comment, he was dismissing his own ability to write something meaningful about what he felt to be the most important thing he’d ever done in his life.

That modesty tracks. I remember my grandpa Charlie as a humble soul who loved to laugh, loved children, felt little pain (for my amusement, he’d put a clothespin on his finger while pretending to sleep), and yet passionately hated human cruelty—especially when wealthy and powerful groups subjugated and exploited others for gain. In contrast with his self-effacing nature, the accounts by others of him during the war in Spain are legendary. They remember Charlie running alone through showers of bullets, despite being hit in his shoulder and knee. (Later, he’d describe those gun wounds as “superficial.”) In a picture of him with two other Lincoln volunteers, he grins while the others appear sullen.

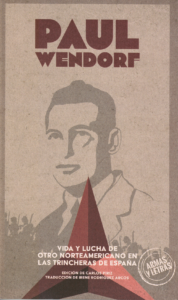

The Volunteers is a one-act play with four scenes that together take about an hour to perform, including musical interludes. After a brief dialogue among three Lincoln vets that seems to take place in the 1970s (“There have been a thousand Guernicas in Vietnam,” one of them remarks), the rest of the story is set in Spain during the Civil War. It features more than twenty characters, about half of whom are Americans. Despite the seriousness of the situation, there is even room for humor. “I’ve always had my doubts about you, Steve,” the character named Charlie remarks, laughing. “Now you’ve confirmed them. You are not a real Communist. You’re one of those deviationists. […] I’m going to report you to the first Commissar we meet—if we get out of here alive. Yes sir, a dogmatic deviationist, that’s what you are. For shame! Karl Marx, to say nothing of Lenin, must be spinning in his grave!” For anyone familiar with the Lincoln Battalion, some characters are easy to recognize: Captain Steve Haines resembles Steve Nelson; Sergeant Charlie is my grandfather; Corporal Sam Levin seems to be partly inspired by Paul Wendorf and a couple of other Jewish volunteers.

Paul would loom large in my grandfather’s life. Born and raised in New York City, he had traveled to Spain in the same group as my grandfather Charlie, who was from Pittsburgh. But while Charlie returned to the United States after eight months, Paul, who was three years older, stayed on. He was killed in action in the Sierra Pandols, during the Ebro offensive, in August 1938. Charlie later married Paul’s widow, Leona—my grandmother. Their first daughter, my aunt Paulette, is named after him.

While in Spain, Paul wrote Leona about 80 long letters that were recently published in Spanish translation, a project made possible by Paul’s cousin, Nancy Phillips, with the help of my sister Sara, who retrieved Paul’s letters from the ALBA collection at the Tamiment Library in New York. It was also Nancy who put me in touch with Patricia Ure and Almudena Cros of the Association of Friends of the International Brigades (AABI) in Spain. I hoped Patricia could possibly help me share grandpa’s play. To my delight, she immediately suggested that it could be translated and stage-read by a small group of actors at the 2025 Jarama March—which, as it happened, would be dedicated to the American volunteers.

While in Spain, Paul wrote Leona about 80 long letters that were recently published in Spanish translation, a project made possible by Paul’s cousin, Nancy Phillips, with the help of my sister Sara, who retrieved Paul’s letters from the ALBA collection at the Tamiment Library in New York. It was also Nancy who put me in touch with Patricia Ure and Almudena Cros of the Association of Friends of the International Brigades (AABI) in Spain. I hoped Patricia could possibly help me share grandpa’s play. To my delight, she immediately suggested that it could be translated and stage-read by a small group of actors at the 2025 Jarama March—which, as it happened, would be dedicated to the American volunteers.

Fast forward to February 20, 2025, the day of the staged reading at the Ateneo de Madrid. I was nervous, unsure what to expect. Since there was to be a colloquium following the play, I had prepared a short speech to express my gratitude to Almudena and Patricia, as well as the director, actors, translator, and musical director. As a group of us walked from the Hotel Agumar to the Ateneo, we saw a line of 75 or more people outside. My first thought was that there must be another, simultaneous event going on. Perhaps, I figured, The Volunteers would be performed in a small upstairs room. I realized I was wrong when I was escorted into a large theatre with balcony seating and assigned a seat in front, from where I could witness a “full house” at the theatre. (See a photo gallery of the event, by Nancy and Len Tsou, here.)

I was enchanted from the start. Jeannine Mester gave a wonderful introduction in English and Spanish. The translation of the play, by Andrés Chamorro of AABI, was masterful, as was Nacho Vera’s musical production and the vision of the director, Juan Pastor. The characters —Steve, Charlie, Sam— sang satirical and wistful war songs, performed a comical court-martial scene between Slim, a soldier, and his superior, Big Mike, culminating into their coming to ideological grips with the significance of their service in Spain. The ending had me in tears and on my feet to applaud the four fabulous actors: Jeannine Mester, Javier Madruga, Luis Miguel, and Carlos Manrique. Together they bestowed the greatest honor on my grandfather. Our family will forever be grateful to AABI for making this possible, and we are delighted to make the play available in pdf for sharing and on YouTube for viewing.

Kate Fogarty, Charles Nusser’s granddaughter, is an associate professor of Family, Youth, and Community sciences at the University of Florida. She and her sister, Sara, went to Spain in 1994 to commemorate Charles Nusser after his death in 1993 by scattering his ashes throughout his favorite places in Madrid and Barcelona. Their mother, Helen Fogarty, and aunt, Paulette Dubetz, are equally invested in their father’s quest to maintain the memory of the Spanish Civil War and to promote education and awareness on fascism.