A Visual Testament: The Lincolns and Camp Kinderland

Camp Kinderland was first established 102 years ago by Jewish working-class immigrants who wanted to take their children out of the city’s hot summer streets and, through the camp program and its related Yiddish shul, familiarize them with their progressive Jewish traditions and heritage. Through the years, Camp Kinderland has upheld the principles that its founders and leaders valued, as campers learned about struggles for workers’ rights, civil rights, and social justice, as well as other important issues of the day.

One spirited event that embodies these principles is the Camp’s Peace Olympics, which were first celebrated in 1956, and through which campers and staff work in mixed-age teams, competing athletically and creating cultural presentations. Initially the focus was on internationalism and labor, with teams named for countries, liberation struggles, or labor unions. Later, activist struggles were included as well. Over the years, as the camp developed a theme for each summer, teams have focused on issues as diverse as the movements around climate, anti-racism, Japanese peace, the Immokalee Workers, activist artists, and Israeli Refuseniks. This past summer, the Olympic teams were the Lincoln Brigade, Stop Cop City, the 504 Sit-Ins, and Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners.

The theme of this summer’s camp program was “None are Free until All are Free: Put my Name Down.” It focused on one central lesson: that all our struggles are interconnected. When we say that “my freedom is bound up in yours,” we don’t simply mean that we are all humans, or that we are nice people who care about others, or that we try to have empathy (though we do hope campers see all those perspectives, too). What we mean is that freedom—freedom from domination; from genocide; from capitalist exploitation; from racism; from prisons and surveillance; from state control over our bodies; from the ways society is built to exclude bodies not seen as productive, bodies disabled and trans; from colonial forces extracting land and indigenous lives—is something we must all join together to wrest from the hands of power.

The Lincoln Brigade is a special Olympic team because among those who put their names down and joined the Lincoln Brigade in the late 1930s were staff and ex-campers of Camp Kinderland. Some of them wrote letters to camp from the frontlines. Yosl Kutler, a poet who frequently visited Kinderland, wrote a poem that became a battle hymn among the Jews fighting in Spain. The songs and art brought to and from the Lincoln Brigade inform anti-fascist imagery and protest even today, as the Spanish Civil War is considered an enduring reminder of our collective duty to fight against fascism, for democracy, and for an international, anti-capitalist coalition that values working people over despots, private business, and industrial militarization. With this team, we honor our Kinderland ancestors and embolden ourselves to fight anti-fascist struggles today.

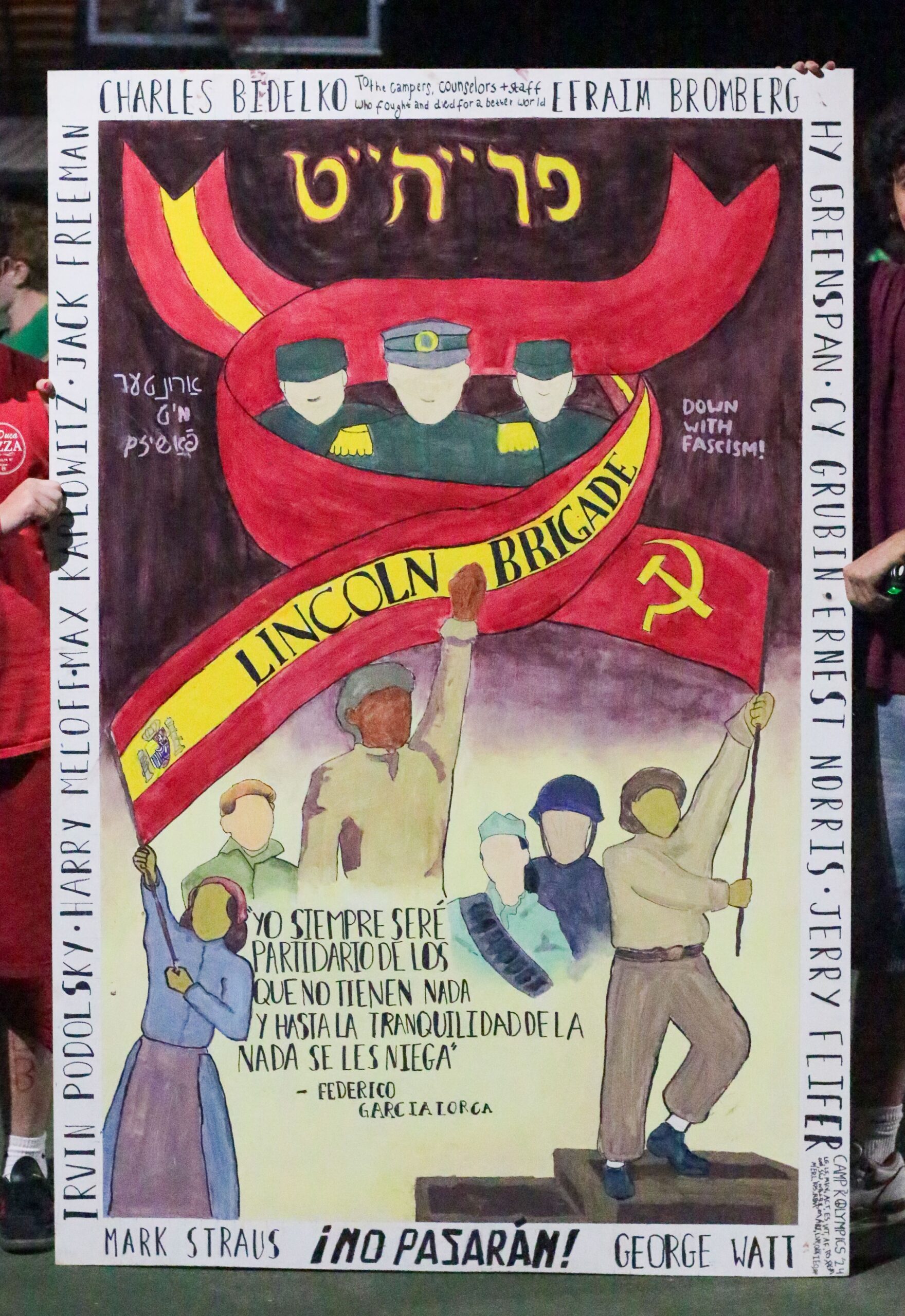

As part of the cultural program for the Peace Olympics, each team creates a mural, painted on 4×8-foot plywood boards, that usually features the team name and a quote from a leader of the movement. The mural is entirely designed and executed by the campers and Counselors-in-Training of that team. For the Abraham Lincoln Brigade team mural (see photo), we wanted to focus specifically on the communist and Marxist ideology of the International Brigades, the anti-fascist values of the Spanish Republicans (thus the prominent hammer-and-sickle flag), and the fact that many of those who enlisted to fight in the International Brigades were civilians. The individuals depicted are all regular people—heroic, yes, but not superhuman. Their poses may be confident—gallant, even—but we took pains to ensure that they did not look statuesque, deified, or Herculean. We left their faces featureless to invite self-identification, a reminder that someday we may all find ourselves taking to arms for a cause that we must defend.

We chose to represent the central character in the mural as being of African descent to honor Commander Oliver Law, the first Black man in the history of the United States to lead a military unit that included white soldiers into battle. His left fist is raised in the salute of the Popular Front. The top of the mural reads “Freiheit”—freedom in Yiddish. This is in reference to three things: the Morgen Freiheit, the anti-fascist Yiddish-language newspaper for which one of the bunks in camp is named; the popular German march of the same name sung by the Thaelmann Battalion and its counterparts; and as a commemoration of the long tradition of Jewish and Yiddish anti-fascist resistance, a tradition to which Camp Kinderland proudly belongs.

In keeping with the theme of honoring Kinderland’s legacy, we chose to add a border that features the names of the thirteen Kinderland campers and staff who fought in the Lincoln Brigade. These are the names of family members, friends, and relations of current Kinderlanders. For many it was moving to see their loved ones —perhaps a friend’s grandfather, perhaps a grandfather’s friend—invoked in a way that closed the gap between history and personal acquaintance. It was paramount to us to pay tribute to our ancestors and elders who fought for a better world and to hold them in our minds while we continue our struggle. To embody this struggle and to tie in the theme of “None Are Free Until All Are Free,” we selected a quote from Spanish playwright, author, and poet Federico García Lorca, who was murdered by the Spanish fascists. Translated, the quote reads: “I will always be on the side of those who have nothing, and to whom even the peaceful enjoyment of that nothing is denied.”

Lalo Garskof, 16, is a junior at Cambridge Rindge and Latin School in Cambridge, MA. This year marks his seventh year as a camper at Camp Kinderland.