How Did Spaniards in the US Experience the Spanish Civil War?

From March 1 to August 3, 2025, The Tampa Bay History Center will host an exhibition titled “Invisible Immigrants: Spaniards in the US, 1868-1945.” Co-curated by Luis Argeo and James D. Fernández, this show uses materials—photographs, documents, letters, keepsakes—digitized or on loan from the family archives of the descendants of those immigrants, as well as oral histories from those same descendants, to tell the story of this little-known diaspora. The Spanish Civil War represents a crucial chapter in that story and in the exhibition, not only because of how, from 1936-39, the war galvanized working-class Spanish immigrant communities all over the United States, but also because the outcome of the war—the victory of fascism, and the ensuing Francoist dictatorship—all but snuffed out the dream, harbored by many of the immigrants, of someday returning to Spain. The exhibition also lays out how the chill of the Cold War and McCarthyism, transformed the way in which the immigrants and their descendants would remember and talk about —or forget and silence—their own past, particularly those years of ardent pro-Republican mobilization. We have asked the curators of the exhibition to showcase some of the Spanish Civil War-related highlights of this fascinating story of remembering and forgetting.

From March 1 to August 3, 2025, The Tampa Bay History Center will host an exhibition titled “Invisible Immigrants: Spaniards in the US, 1868-1945.” Co-curated by Luis Argeo and James D. Fernández, this show uses materials—photographs, documents, letters, keepsakes—digitized or on loan from the family archives of the descendants of those immigrants, as well as oral histories from those same descendants, to tell the story of this little-known diaspora. The Spanish Civil War represents a crucial chapter in that story and in the exhibition, not only because of how, from 1936-39, the war galvanized working-class Spanish immigrant communities all over the United States, but also because the outcome of the war—the victory of fascism, and the ensuing Francoist dictatorship—all but snuffed out the dream, harbored by many of the immigrants, of someday returning to Spain. The exhibition also lays out how the chill of the Cold War and McCarthyism, transformed the way in which the immigrants and their descendants would remember and talk about —or forget and silence—their own past, particularly those years of ardent pro-Republican mobilization. We have asked the curators of the exhibition to showcase some of the Spanish Civil War-related highlights of this fascinating story of remembering and forgetting.

In the roughly five decades leading up to the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), tens of thousands of working-class Spaniards migrated to the United States. They were but a drop in the vast wave of the millions of migrants who left Spain for the Americas in those same years, though the majority of this diaspora would end up in Argentina, Uruguay, Cuba, Mexico, or other parts of the Spanish-speaking world. Those who chose to come to the US settled in tight-knit enclaves scattered all over the country, from Maine to California, from Hawaii to Florida. Many of these migrants were from Spain’s northern Cantabrian coast (Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, Basque Country), though Spaniards from all over the peninsula and its islands took part in this diaspora. Like most migrations, this one too was driven primarily by the search for opportunity—that is, better salaries, better working conditions, more social mobility. If the Spanish migrants were lured or pulled toward the US by the promise of better employment, they were at the same time pushed out of Spain by endemic economic and political injustice—oligarquía y caciquismo, in the shorthand of the time—and by a mandatory military service requirement that was perceived by many as a virtual death sentence, especially during the intermittent colonial wars that Spain waged in North Africa in the early twentieth century.

Typically, unaccompanied men from a given village or county, having learned of a concrete employment opportunity in the US, would migrate and establish a foothold in a specific location, and in a specific economic sector. Often, though not always, their jobs in the US were related to the kinds of work they did in their homeland: e.g. Asturian miners and zinc workers in West Virginia; Cantabrian stone cutters in the granite and marble quarries of New England; Basque and Galician seamen in the ports of New York City. If things went well, these trailblazers might then call for male relatives—brothers, cousins, nephews—to join them in the foundry, coal mine, quarry or shipyard. If things went very well, they might then send for their wives or girlfriends. Finally, if that community reached a critical mass, more diverse employment opportunities would emerge within the enclave, as the growing Spanish migrant community favored businesses run by their compatriots: a boarding house for new arrivals, a grocery store/restaurant, a butcher, a shoe repair shop, or a barber shop, for example. This is the general pattern of development that can be found in Spanish colonias big and small throughout the US in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: not only in more likely places like New York and Tampa (Florida), but also in unsuspected locations such as Donora (Pennsylvania), Canton (Ohio), East St. Louis (Illinois), or San Leandro (California).

Most of these Spanish enclaves grew steadily in size and cohesiveness throughout the 1920s. Like many other immigrant groups arriving in a country with no social safety net to speak of, the Spaniards eventually formed all manner of clubs, associations, and mutual aid societies, in order to make common cause and to collectively confront the rigors of living in a foreign and often hostile land. These clubs might have been social, athletic, cultural, artistic, or political in name and original purpose, but the solidarity that they all embodied and the networks that they all wove would become especially crucial in the wake of the stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression.

Many of these migrants—peasants or industrial workers—came to the US with a developed working-class left-wing political culture, ranging from anarchism through communism and to socialism; some were further radicalized in the US in the ideological strife and struggles of the Great Depression. Most of them greeted the advent of the Second Republic (1931) with cautious optimism, if not outright enthusiasm. By the time of the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July of 1936, there was an archipelago of vibrant and relatively well-organized Spanish colonias spread all over the United States. Within days of the outbreak of the war, many of these organizations would repurpose their inward-looking social or cultural or sporting events into fundraisers aimed at helping the Republic defend itself from the fascist onslaught. During the war, scores of these Spanish migrant associations in the US joined an umbrella organization known as the Sociedades Hispanas Confederadas, that strived to coordinate the efforts being made by the member clubs in support of the Republic.

As you will see in this selection of items from the exhibition, the family archives of the immigrants’ descendants profusely document their intense commitment to the Second Republic, even if the memories of their descendants are often blurry, vague, or even distorted beyond recognition.

James D. Fernández is Professor of Spanish at NYU, director of NYU Madrid, and a longtime contributor to The Volunteer. Luis Argeo is a journalist and documentary filmmaker currently based in Gijón, Asturias, Spain.

SCENES FROM AN EXHIBITION: CHAPTER 4, SOLIDARITY AND STRIFE

This photo of Spaniards attending a picnic in Monterey California is decontextualized because the inscription on the upper right-hand corner has broken off or been removed. Even though a close look reveals a good number of popular front salutes and even a republican flag, many descendants often don’t perceive or appreciate the political context of the image. We eventually found an unmutilated print of the photo and learned what the lost inscription reads: “Picnic to benefit widows and orphans of the Spanish Civil War, organized by Acción Demócrata Española, Monterey, California, May 27, 1937.” (Courtesy of Roberto Fabián Martín.)

Asturian metalworkers and Andalusian copper miners from Riotinto, Huelva converged in Canton, Ohio in the teens and twenties. The Canton-Cleveland area was a hotbed of pro-Republican mobilization among Spanish immigrants, as evidenced in this extraordinary photo of the Youth Chorus of the Anti-Fascist Committee of Canton, Ohio. (Courtesy of the Pujazón family).

All over the United States, we have seen dozens of photographs like this one, in which Rose Cividanes, the daughter of Spanish immigrants in New York dons the clothes and pose of a Republican miliciana. (Courtesy of the Cividanes family)

Rose Cividanes, 80 years later, poses with the photograph shown above.

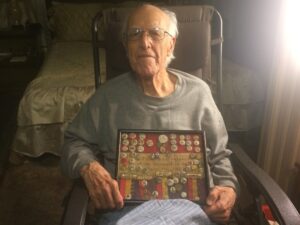

Manuel Zapata (RIP) was just a young boy when he put together this astonishing collection of pro-Republican pins produced by a wide range of New-York-based Spanish immigrant clubs and associations. (Courtesy of the Zapata family)

“Spanish women to protest State Department. Washington, D.C., April 4. Three thousand Spanish-born women from large eastern cities, led by the widow of an American killed in Spain’s Civil War, marched on the State Department today where they made a formal plea to “revoke the arms embargo against the democratically elected Government of Spain”. The widow who headed the delegation was Mrs. Ernestina Gonzales, PH.D. and former Director of the Madrid University Library.”

Photo and caption from the Library of Congress

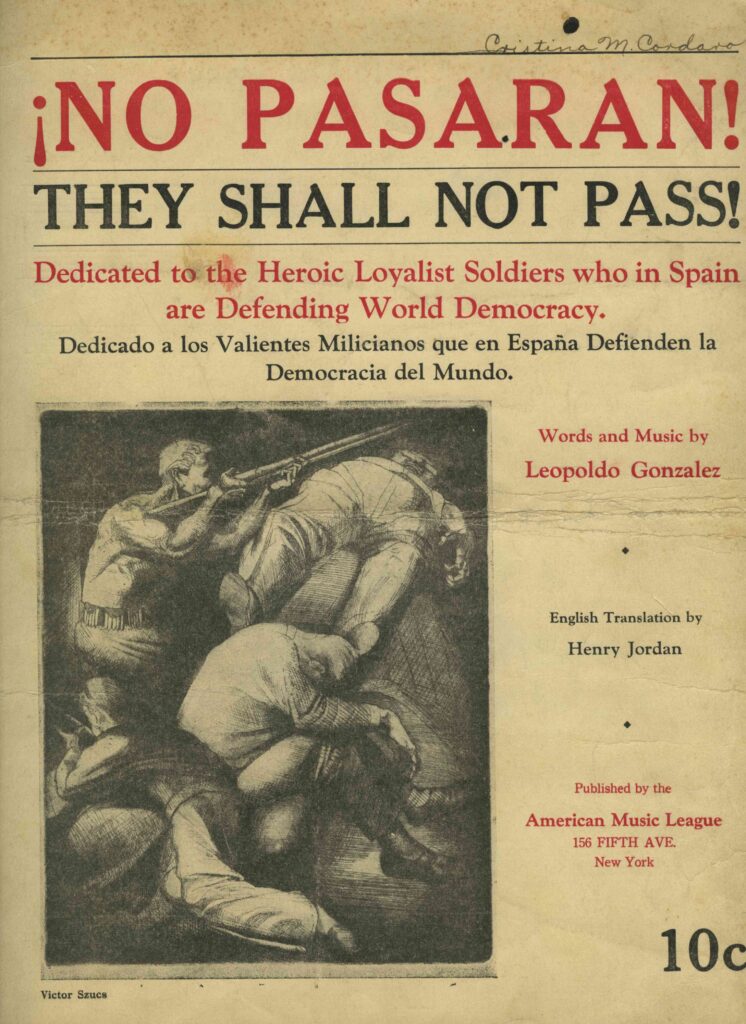

Home to a large population of antifascist Spanish immigrants, Tampa, Florida was without a doubt, one of the most active centers of pro-Republican mobilizations in the US. The tampeño cigar worker, Leopoldo González, composed the song “No pasarán” which would become the unofficial anthem of Spanish immigrant communities who would sing it at rallies from coast to coast. (Courtesy of the Fernández family)

Invisible Immigrants: Spaniards in the US was produced and sponsored by the Fundación Consejo España-EEUU. It can be visited between March 1 and August 3 at the Tampa Bay History Center in Tampa, Florida. More details at www.emigrantesinvisibles.com.