Tributes and Re-enactments: Civil War Days in Azuara, Aragón

“The past isn’t dead,” William Faulker famously wrote; “it isn’t even past.” The quote came to mind me while attending a remarkable gathering last September in the ancient Spanish town of Azuara, a small community of roughly 500 inhabitants, 40 miles south of Zaragoza (Aragón).

Azuara was transformed by the Spanish Civil War. Over three years the town endured several changes of power, with control alternating between Falangist, Anarchist, Republican, and finally Fascist forces. Incidents of brutal repression accompanied every change in the local regime, including targeted murders, mass killings, expropriation of property, and anticlerical violence. Many families had no choice but to flee to mountains and caves.

In March 1938, Azuara was squarely in the path of a fascist offensive. Republican units faced history’s first “blitzkrieg,” a fully motorized army with heavy artillery, tanks, and German air power. The offensive succeeded in splitting the Republic in two, routing Republican forces in what became known as the Great Retreats. In Azuara, a dozen volunteers, part of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion (the “Mac-Paps”) of the International Brigades, lost their lives while providing machine gun cover for their retreating comrades. This particular group—8 Finns, 3 Canadians, and 1 American—embodied the global make-up of the men and women who came to the aid of the Spanish Republic.

The Azuara gathering, several years in the planning, was led by the 28-year-old Erik Salvador Artigas, who presides over the Historical Recovery of Azuara Association. The event attracted an extraordinary mix of people to commemorate events and to celebrate local resistance to the fascist assault. The inspiring turnout of several hundred local townspeople, as well as the communal feeling generated by the various events, made the occasion quite different from the typical academic conference.

On a bright, crisp Saturday morning we visited the original trenches built on the outskirts of town, with dozens of huge wind turbines providing a surreal backdrop. (Locals explained that the rent farmers received for the use of their land far exceeded what they could get for growing olives. Some of us also thought of Don Quixote, tilting at windmills.) Uniformed re-enactors filled the trenches, shouting orders, and simulating gunfire. We then visited the indoor exhibition housed in an old villa and put together entirely by locals. A bilingual text accompanied by enlarged photos recounted how the town experienced the civil war, including the mass execution of hundreds of Azuarans in the summer of 1936 by Guardia Civil units siding with Franco. The Mac-Pap volunteers who helped defend the town during the Great Retreats received a lot of space. I was stunned and moved to tears upon seeing a large picture of Leo (Mendelowtiz) Gordon, my father’s cousin—and the lone American in the group of 12 Mac-Paps who perished there in March 1938. A young Spanish visitor from Zaragoza joked that she could tell Leo was an American because he was the only one smiling and he had good teeth. Civil war posters, a display case of small weapons, and a section on food and kitchens evoked the textures of everyday life. We then enjoyed a tasty communal lunch of paella, prepared in one giant pan that fed around 250 people.

After lunch a couple hundred of us toured the caves where many Azuarans were forced to live during the war. In one we watched a recreation of a hospital treating the sick and wounded. There followed a recreation of the battle atop a high cliff where the Mac-Paps had been cut off as the Republican forces retreated from the town. After providing cover for 8-12 hours the men were captured and then executed by firing squad. A large crowd, including many children, watched silently, almost as if in church, as actors dressed in period uniforms and bearing vintage weaponry played Republican and Fascist troops and women dressed in 1930s nurse’s garb.

The battlefield re-creations reminded me of the creepy cosplay of neo-Confederates in the American South, but locals said that communities all over Spain consider them a crucial part of educating the young about the civil war. Thankfully, when they portrayed the capture and execution of Leo and the others, we only heard the rifles firing behind nearby trees.

As the events in Azuara invited a cross-section of people to discover more about the experiences and fates of relatives who had volunteered to fight for the Republic, we felt ourselves a modern-day echo of the Popular Front’s internationalist spirit. Andrew Johnson and Jane French traveled from Toronto to learn about his uncle, Arthur Johnson, who served with the Mac-Paps and was KIA at Gandesa during the Battle of the Ebro. The family never knew what happened to him. In casual conversation, Andrew and I discovered that his uncle Arthur and my uncle, Ben Barsky, had been killed in the same battle. Among others, I connected with Martin and Debbie Paivio from Aurora, Ontario; Ben Pratt from rural Maine; Mikko Ylikangas from Helsinki; and Claudia Honefeld from Hamburg. The large Finnish contingent that died at Azuara attracted the attention of Finnish TV, which interviewed several of us, as well as the Finnish Ambassador to Spain, Sari Rautio. Several went on tours of nearby historical sites conducted by Alan Warren, a British expat based in Barcelona who runs the Porta de la Historia Cooperativa (SCCL) there. Alan has long been an invaluable resource for people visiting Spain to research the civil war.

Later in the town hall, some of us delivered papers on various aspects of the war in Azuara and the Mac-Paps’ experiences, as some 300 people, made up mostly of local citizens, listened intently to what we had to say. Janette Higgins spoke about her father, Jim Higgins, a Mac-Pap veteran whose memoir she recently edited and published. After she spoke, scores of audience members lined up, waiting patiently for Janette to sign Spanish edition copies of her book, Fighting for Democracy. My talk was translated into Spanish by Susana Moreno, who, like several others, had graciously volunteered to do it. This was by far the largest and most considerate audience I’ve ever had for a historical event.

Later in the town hall, some of us delivered papers on various aspects of the war in Azuara and the Mac-Paps’ experiences, as some 300 people, made up mostly of local citizens, listened intently to what we had to say. Janette Higgins spoke about her father, Jim Higgins, a Mac-Pap veteran whose memoir she recently edited and published. After she spoke, scores of audience members lined up, waiting patiently for Janette to sign Spanish edition copies of her book, Fighting for Democracy. My talk was translated into Spanish by Susana Moreno, who, like several others, had graciously volunteered to do it. This was by far the largest and most considerate audience I’ve ever had for a historical event.

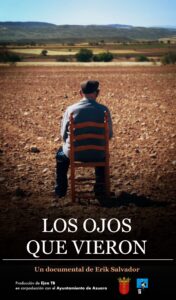

The conference closed with the premiere of Los Ojos Que Vieron (The Eyes That Saw), a powerful documentary directed by Erik Salvador Artigas and produced by Antonia Fuentes and Jose Lezcano, with support from the Azuara City Council. The film uses interviews with survivors and their descendants, along with found footage from the 1930s, to tell the complex story of one town’s civil war. Plans are underway for a more general release and a version with English subtitles.

As I watched the film, screened before a packed house, I wondered if more Spanish towns might produce their own versions of Azuara’s astonishing weekend. In the 1930s, tens of thousands of volunteers streamed to Spain to defend the Republic. Today, an increasing number of people and organizations are determined to keep their history alive and educate their home countries. As America faces a resurgent neo-fascist threat at home, digging into the stories of those who resisted Fascism is more urgent than ever. William Faulkner would have understood.

Daniel Czitrom is Chair Emeritus of the ALBA Board of Governors. He can be reached at dczitrom@mtholyoke.edu.