William Lindsay Gresham’s Spanish Civil War Poetry: Beyond “Last Kilometer”

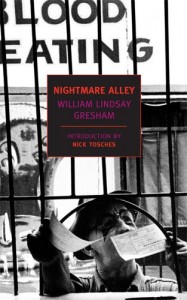

Lincoln vet Bill Gresham’s Nightmare Alley cemented his fame as a noir novelist. Yet most of his Spanish Civil War poetry was never published—until now.

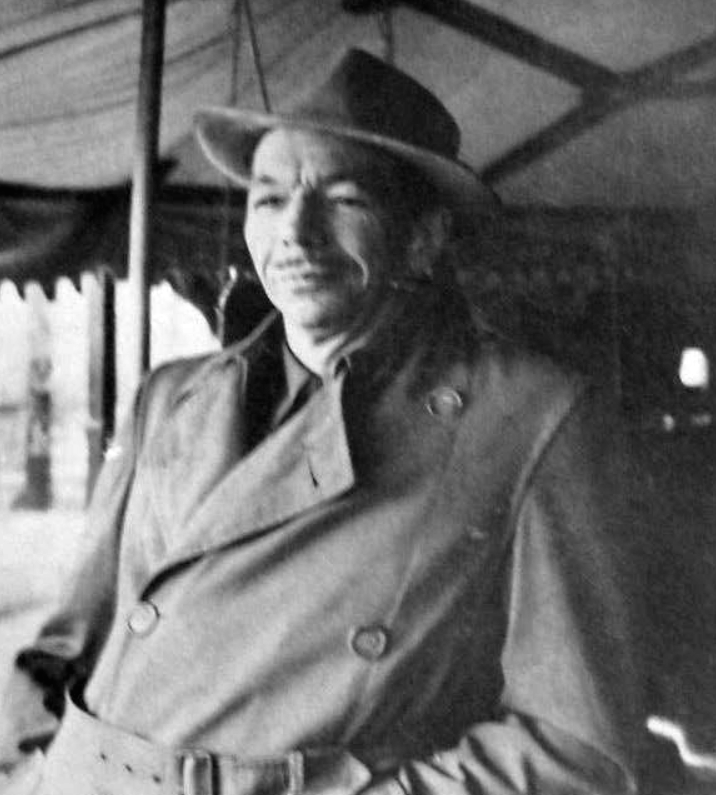

William Lindsay Gresham (1909-1962), the Lincoln Brigade veteran whose bestselling crime novel Nightmare Alley (1946) inspired two films, was never the same after the Spanish Civil War. He rarely mentioned it, but all sources agree that Gresham’s many troubles—alcoholism, a psychotic episode, at least two suicide attempts before he killed himself in 1962—came afterward.

As ALBA’s Chris Brooks reports, Gresham was in Spain from November 1937 to February 1938, mostly as a medic on the Teruel and Levante Fronts. Fellow soldier Ben Iceland remembers Gresham writing skits for a Christmas Eve celebration, and spending time with Joseph Daniel “Doc” Halliday, also known as “Spike.” In fact, Halliday’s descriptions of the carnival life, particularly how alcoholics get recruited to play feral chicken-eating men in “geekshows,” inspired Gresham to write Nightmare Alley, whose success he was never able to replicate.

Three years after the novel came out, Gresham published his poem “Last Kilometer” in War Poems of the United Nations, edited by his then-wife, Joy Davidman. It would be his most direct statement about Spain. Its stark depiction of what it’s like to enter a war zone has been reprinted in several collections, including The Wound and the Dream and The Neglected Poetry.

While most Gresham fans are familiar with his Spanish Civil War service, “Last Kilometer” doesn’t seem enough to consider him as a war poet. But we now know that he wrote more poems about the war. After Gresham’s third wife, Renée, passed away in 2005, his papers went to the Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College. It was there that, in 2023, I came upon a folder labeled “Poems, 1941-1944.”

While most Gresham fans are familiar with his Spanish Civil War service, “Last Kilometer” doesn’t seem enough to consider him as a war poet. But we now know that he wrote more poems about the war. After Gresham’s third wife, Renée, passed away in 2005, his papers went to the Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College. It was there that, in 2023, I came upon a folder labeled “Poems, 1941-1944.”

Along with several transcripts of famous Spanish Loyalist songs, the folder contains at least 10 poems Gresham wrote that were never published. Included below are four of these poems, as well as “Hasta Revista,” a poem Gresham likely wrote. (When I contacted Peter N. Carroll about “Hasta Revista,” he said it could be something Gresham had collected, although he had never seen it anywhere before.)

It may seem strange that these poems haven’t been published until now. The sad reality is that little research on Gresham has been done. Perry C. Bramlett and Nick Tosches planned biographies but passed away before finishing their work. What has been published usually connects to Gresham’s most popular books, which appeal to different communities. Fans of Nightmare Alley or its adaptations discuss Gresham as a hardboiled or noir writer. Fans of Houdini: The Man Who Walked Through Walls praise him for writing “the first great Houdini biography.” Even when crime fiction and stage magic scholars share ideas, Gresham’s limited output can make him a niche subject in each.

Gresham also gets mentioned in discussions about Joy Davidman, albeit not always in a fruitful way. After their divorce, Davidman married the Christian apologist C.S. Lewis. Their romance was adapted into a play and two movies, all titled Shadowlands, in the 1980s and ‘90s. Scholars specializing in the Inklings (Lewis and his Oxford writing friends like J.R.R. Tolkien) often mention Gresham, but rarely as a writer in his own right. Until around 2021, he was mostly seen as a footnote in the Lewis-Davidman story—at most an offstage villain endangering their romance.

Fortunately, Gresham’s work is easier to find today than in a long time. Thanks to the 2021 movie adaptation by Guillermo del Toro, Nightmare Alley is back in print, while Dunce Books released a limited edition of his nonfiction book Monster Midway the same year. The William Lindsay Gresham estate has let me publish two Gresham poems elsewhere: a Norse myth piece called “Rahnhild,” and an ode to C.S. Lewis called “The Friar of Oxford.” I hope that publishing these Gresham poems about the Spanish war will spark new discussions.

Hasta Revista

(tune: “Spanish Ladies”)

In the hot sun of summer we’d camped in a valley.

A motor-bike rider roared up with the news.

Spanish boys with smooth faces come up to replace us.

We gave them tobacco and sometimes our shoes.

(Chorus:)

Farwell and adieu to you fine Spanish ladies,

Farwell and adieu, all you ladies of Spain.

For we’ve received orders to sail for our homeland

But it’s likely that some day we’ll see you again.

In Valencia we feasted on meat and canned butter.

We sat under palms and we counted the stars.

We slept on a mattress, we shared every morning

And we drank the last cognac they had in the bars.

We waited and cursed all the fine Spanish weather –

We waited for rain and a few of us prayed.

Then the mist settled down, our tramp steamer was waiting,

And we cast off in the darkness to run the blockade.

(chorus)

We crossed the frontier on the last night of freedom,

The bombers came over to search for our train.

Their Falangist banners were in Barcelona

While we rode through the darkness, remembering Spain.

Farewell and adieu to you fine Spanish ladies,

Farewell and adieu, all you ladies of Spain.

For we’ve received orders – to stay in our homeland

But it’s likely that some day we’ll see you again.

New Year’s Eve: Villanueva de Castellon

Four yellow roses shining in moonlight so splendid

It caught at the breath

In a stillness so deep that the year just ended

Smiled in its death.

They were the last things left in the garden

With its black trees

Where oranges, bitter and shriveled, had started to harden

Through nights like these.

If only the rain had come with a lash of thunder

To roll out the year.

But no — in the desperate blaze of the moonlight the wonder

Of life stirred here.

And bitter were all the days of the summer just spent

On hillsides of stone;

And the fear of the end, and the sword blade bent,

And the roses staring alone.

Again Rising

There are old battlefields within me

Where the dead crawl out to meet their death again

And the artillery spouts fire

In silence, served by sweaty, silent men.

Towns are bombarded that are dust

And camions roll under a sun gone down.

And hills are ours by blood that’s dry

In ditches near a long-deserted town.

In Elche on its canyon edge

The palms still rattle in the moonlight’s breath.

(They burned as the town turned,

Long ago, long ago its hot death.)

If I returned I would search the places

And haunt the roads again, looking for a sign.

There is no returning. But in sleep

I reach for the dead fingers and I find them mine.

Compulsion Before Dawn

I must go back when brotherhood has won

its death-lock over destruction’s host of hate

to watch an ancient sea lick at the gate

of cities lifting marble to the sun.

I must seek olives where a single gun

chattered its lone defiance hours too late.

I must tread terraces where I scattered fate

and tie up threads of purpose left undone.

Now through their mouths who shared the raw, new wine

the maggots crawl. And through the hollow brain

they twist and dig in tissue rightly mine,

in graves my destiny filled with better men.

there, on the rusting wire by our old line

of trenches, shall find my heart again.

One

Every heaven’s creature

Of some earth tastes.

If the bird dies

My labor wastes.

Every bird’s fall

Has crushed my bone.

I find my own death

Under a stone,

Blind and white-burrowing,

Ugly I,

Suddenly pitiful:

Cry! Cry!

(“One,” “Compulsion Before Down,” “Again Rising,” “New Year’s Eve: Villanueva de Castellon,” and “Hasta Revista” by William Lindsay Gresham. Copyright © by William Lindsay Gresham. Reprinted by permission of The Estate of William Lindsay Gresham and Brandt & Hochman Literary Agents, Inc. All rights reserved.)

Connor Salter is a writer and editor who has contributed over 1,400 articles to various publications, from local news to film studies. His research on Gresham has appeared in the Edinburgh University Press Blog, Fellowship & Fairydust, Punk Noir Magazine, The Journal of Inklings Studies, Mythlore, and Mystery*File.