Dr. Barsky and the Paradoxes of Refugee Aid

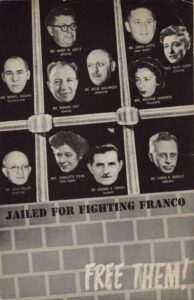

Eleven board members of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee hold a press conference in Washington prior to surrendering before Judge Richmond B. Keech to begin prison terms for contempt of the Un-American Activities Committee. Seated left to right: Dr. Lyman R. Bradley; Mrs. Ruth Leider; Dr. Edward K. Barsky, chairman; and Mrs. Charlotte Stern. Standing left to right: Mr. Harry M. Justiz; Dr. Louis Miller; Mrs. Marjorie Chodorov; Mr. Manuel Magaña; Mr. James Lustig; Dr. Jacob Auslander; and Mr. Howard Fast. Acme Telephoto. Colorized.

For Edward Barsky, political and humanitarian activism were two sides of the same coin. Those who persecuted him begged to differ.

The worldwide campaigns on behalf of the Spanish Republicans that began in 1936—and which continued for many years after the Republic’s defeat—betrayed a curious tension. On the one hand, the Spanish people appeared in posters, newsreel footage, documentaries, and photographs as political heroes bravely fighting on the frontline of the struggle against world fascism. On the other, they were portrayed as defenseless victims in need of protection and aid. This same tension runs through the many refugee aid organizations that emerged in the wake of the Spanish war and grew in scale during and after World War II. At its heart are two larger questions: Are mass displacements caused by political conflict a humanitarian or a political phenomenon? And is helping refugees a humanitarian or political act?

Hannah Arendt famously argued for a political interpretation. The ability of states to simply expel entire communities, she pointed out in The Origins of Totalitarianism, is a perverse byproduct of the doctrine of state sovereignty. The statelessness of refugees, in effect, robs them of their rights. “No paradox of contemporary politics is filled with a more poignant irony,” Arendt wrote in 1951, “than the discrepancy between the efforts of well-meaning idealists who stubbornly insist on regarding as ‘inalienable’ those human rights, which are enjoyed only by citizens of the most prosperous and civilized countries, and the situation of the rightless themselves.” “The popular idea that the world refugee problem is somehow independent of politics is certainly touching,” Roger Rosenblatt remarked later. “But it is also stupid and dangerous. The confusion works to the great advantage of the world’s more malevolent leaders […] because the preoccupation with suffering, any suffering, diverts attention from what produced that suffering in the first place.”

If the distinction between politics and humanitarianism in matters of refugee aid seems fuzzy, it was nevertheless crucial to the thousands of U.S. citizens who felt deeply affected by the events in Spain and compelled to do something to help. The distinction was especially important to the fundraising efforts on behalf of Republican Spain during and after the conflict. After all, the neutrality laws that the U.S. Congress had adopted in 1935, 1936 and 1937 expressly prohibited any contribution to the military effort, leaving a small legal loophole for collections for “purely” humanitarian purposes. Once the Republic had been defeated, the same legal and fiscal limitations applied to the many organizations providing aid to refugees.

Yet, ironically, the legal framework that made the aid possible in the first place ended up being the source of its demise. The mere suspicion that entities like the one headed up by Barsky may have had political motives was enough to paralyze them almost completely. As Phillip Deery writes in this issue, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) justified its investigation and persecution of Barsky and company after World War II by alleging that they were involved in subversive political propaganda instead of humanitarian work.

How could things have come this far? Almost immediately after the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, hundreds of groups emerged across the US that identified with the Republicans, the most important of which was the North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy (NACASD o NAC). Founded in October 1936 at the initiative of the American Friends of Spanish Democracy and other allied groups, the NAC was directed by the Methodist bishop Francis McConnell and the reverend Herman Reissig. The American Friends also created the Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy (MBASD), headed by Dr. Barsky. The MBASD and NAC merged in January 1938.

Both organizations were “Popular-Frontist” in nature, uniting a broad range of antifascists, from pacificists and liberal progressives to Communists and Socialists—the kind of broad unity in the face of fascism that Georgi Dimitrov, head of the Communist International, had called for in the summer of 1935. Like many of the organizations inspired by Dimitrov’s appeal, the NAC and MBASD benefited from the expertise and organizational capacity of the Communist Party members, without necessarily ceding all institutional control to them.

Between 1936 and 1939, the NAC and MBASD undertook a series of successful campaigns that attracted broad media attention and allowed them to raise significant funds that allowed the Bureau to send medical personnel, drugs, ambulances and other goods to Republican Spain, where Barsky was doing an extraordinary job organizing the Republican army’s medical services and hospital installations. Pro-Republican organizations in the United States also applied pressure to the Roosevelt administration to abandon neutrality, lift the arms embargo on Spain, and intercede on behalf of Spain’s democratically elected government.

Around the time of the Republic’s defeat in 1939 and the ensuing crisis—up to half a million Spaniards were estimated to have fled to France—several pro-Republican organizations decided to dissolve or turn themselves into nonprofits exclusively devoted to aid to prisoners and refugees. In the US, organizations providing this type of aid included the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), the Unitarian Service Committee (USC), the Spanish Refugee Relief Campaign (SRRC), the International Relief Association, and the Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC), which would later merge with the International Rescue Committee (IRC). Although all these organizations defined their mission as exclusively humanitarian, and several worked together, their job was hampered by political tensions.

In April 1939, the NAC/MBASD transformed itself into the Spanish Refugee Relief Campaign (SRRC), with a purely humanitarian profile and with “no connection with any political group.” The decision to minimize the political profile of the old NAC was both tactical and pragmatic. The half a million Spanish refugees in southern France posed a tremendous humanitarian challenge, whose solution demanded an unprecedented fundraising effort. More than ever, it was necessary to appeal to the broadest possible segment of the U.S. population. No one doubted that clear political affiliations would prove counterproductive for this effort, especially among the various religious communities. Similarly, it was necessary to depoliticize the organization in order to make it eligible for the increasingly generous funds that the U.S. administration and other governments were setting aside for refugee aid in Europe through the National War Fund (1943-47) and the War Refugee Board (1944-45).

The SRRC’s main task was to maintain the American public interest for the Spanish problem, to convince it that the suffering of hundreds of thousands of Spanish refugees in the south of France was unjust and unacceptable and persuade it of the fact that the urgency of the situation transcended any kind of particular political interest. With those goals in mind, the SRRC developed several media campaigns. This made sense: Photography and film had already been central to media coverage of the war, as well as in both camps’ efforts to secure international support.

In fact, the refugee crisis intensified the role of photojournalism. The images of the thousands of desperate refugees who starting in January tried to cross the Spanish French border were more dramatic than ever. But these pictures did not only appear in magazines and newspapers. Robert Capa and other war photographers allowed the SRRC and other refugee organizations to use their images for their awareness and fundraising campaigns, trying to turn the public’s outrage into a philanthropic impulse.

In the course of 1939, the New York office of the SRRC and its more than one hundred delegations across the United States undertook a broad range of projects. The most ambitious was a fundraising campaign around a 30-minute documentary film on the French concentration camps in which the hundreds of thousands of Republican refugees languished. Entitled Refuge, it was a dubbed and shortened version of the French film Un peuple attend (A People in Waiting), directed that same year by Jean-Paul LeChanois (aka Jean-Paul Dreyfus). It included newsreel footage but also original takes of life in the camps, shot with a camera hidden in a grocery bag.

But, as it turned out, the Refuge campaign would be the SRRC’s last large project. As many other Popular-Front organizations, it did not survive the consequences of the German Soviet non-aggression pact of August 1939. In March of the following year, a conflict between Communists and non-Communists led to the departure of Barsky and his allies. Those who left formed their own independent organization, devoted primarily to a “Rescue Ship Mission”—a boat that would transport the Spanish refugees to Latin America—but that project, too, ran aground due to internal conflicts and barriers that the U.S. government put up. In March 1942, the United American Spanish Aid Committee, the Rescue Ship Mission and the American Committee to Save Refugees merged to form the Joint Antifascist Refugee Committee. Directed once more by Barsky, it poured all its energies in a new campaign: the “Spanish Refugee Appeal.” (The remaining members of the SRRC, meanwhile, ended up joining the Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC), directed from France by Varian Fry, who famously helped save dozens of artists and intellectuals, including Hannah Arendt, Marc Chagall, and Anna Seghers.) Because the JAFRC did not have a license to dispense humanitarian aid in Europe, however, Barsky’s committee allied itself from the start with the Unitarian Service Committee (USC). It was the USC which distributed the funds raised by the JAFRC, under specific conditions set by Barsky’s group. Central among the collaborative projects between the Joint Antifascists and the Unitarians was the Varsovia Hospital in Toulouse.

The Unitarian Service Committee, established in 1940 by the American Unitarian Association as one of the largest and most important U.S. refugee organizations, played a decisive role saving thousands of displaced Europeans before, during, and after World War II. At the height of its activity, the USC managed an annual budget of over a million dollars. These funds came not only the National War Fund, the War Refugee Board and the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, but also from Barsky’s Spanish Refugee Appeal, which over its various years of operation contributed around $300,000.

Yet shortly after the end of World War II, the Unitarians’ refugee work suffered a major blow, thanks in large part to its collaboration with Barsky’s JAFRC, which in late 1945 landed in the crosshairs of Wood and Rankin’s HUAC. HUAC suspected that the Committee was a Communist front organization, which would disqualify it for its federal license as a charitable, tax-exempt organization. HUAC’s investigations of the JAFRC led it to the Unitarians.

In October 1946, a seven-member Unitarian delegation appeared before Wood and Rankin to prove that the USC was a purely American and humanitarian organization—that is, apolitical and not subservient to foreign interests. In a closed session, the Unitarians declared that their Service Committee dispensed aid to all refugees in need of it, independent of their political affiliation, and “as long as there was no attempt to make use of the relief for political purposes.” At the same time, however, they had to admit that the USC had no specific mechanisms in place to prevent the presence of Communists in its ranks. The case stained the Unitarians’ reputation and sparked political conflicts within the Association, while tensing the relations with other refugee aid outfits. Throwing more fuel on the fire, that same year a representative of the rival International Rescue Committee wrote a letter to the Unitarian leadership to complain that two of the USC’s central operatives in Europe, Herta (Jo) Tempi y Noel Field, were giving preferential treatment to Communist refugees, were themselves Communist Party members, and even worked for the Soviet secret police. Around the same time, similar charges surfaced in Toulouse, where several non-Communist organizations alleged that the recipients of USC funds were discriminating against non-Communists. This included the Varsovia Hospital, which in the U.S. was known as the Walter B. Cannon Memorial, named for a well-known surgeon from Boston who had died in 1945. In light of these accusations, Cannon’s widow asked the Joint Antifascist Refugee Committee in 1948 to stop using her late husband’s name. The JAFCR ignored the request. By then, however, the Unitarians had already withdrawn from the hospital project. The episode prompted a purge among the Unitarian ranks.

It was in the context of growing doubt and suspicion that the USC and the JAFRC decided to undertake another publicity campaign that, once again, put visuals front and center. In 1946, they commissioned the German-born filmmaker Paul Falkenberg to produce the documentary Spain in Exile, and in the spring of that same year, the USC hired Walter Rosenblum, a young, Jewish photographer from New York to spend several months in Europe to document the Committee’s extensive work with refugees.

“It is certain that you will dislike the shameful truth that this picture is about to reveal,” Quentin Reynolds, a well-known war correspondent, tells the viewers in his introduction to Spain in Exile. “The picture is the story of a debt—a debt that we owe, a debt that is still on the books. It is an old debt. It was incurred eight years ago, long before Hitler marched into Poland.” The 20-minute film combines newsreel footage of the Spanish Republican exodus in early 1939 with newly shot scenes documenting the lives of the thousands of Spanish refugees remaining in France. The narration links the Spanish Civil War directly to World War II. “We didn’t know then what we know now,” Reynolds’ voice booms over the heart wrenching newsreel images of the Spaniards’ border crossing and their lives in the French refugee camps. “This is what total war looks like. The first experiment in total war and already half a million refugees …” The film goes on to highlight the Spaniards’ role in the fight against the Nazis, their use as forced labor, and their passage through camps like Mauthausen, Dachau, and Bergen-Belsen. It also contrasts their heroism in the struggle against international fascism with their precarious existence in postwar France—“They are underfed, poorly clad,” Reynolds says; “they wear the same clothing winter and summer”—which is similar to their life during the war. At the same time, Spain in Exile highlights the good work done by the Joint Antifascist Refugee Committee through the Unitarian Service Committee at the Varsovia Hospital and elsewhere. After the film’s closing scene, Reynolds reappears on the screen with a final appeal to the viewers:

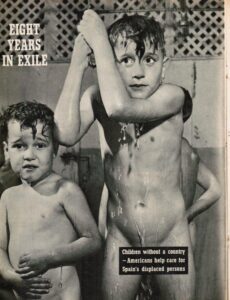

You have just seen the truth about the first victims of total war. It is not enough just to stand appalled. Our job is to see that the heroic men and women who struck the first blows against Hitler and Franco do not remain the forgotten fighters of World War II. The children you have seen in this picture are the hope of Spanish democracy. Boys and girls who were baptized in the blood of their fathers fighting in Spain are the chief concern of the Committee. I hope they are your concern, too.

Here are some still images from the film:

- Quentin Reynolds

- Spanish refugees

- Spanish refugee

- Jo Tempi

- Pablo Picasso

- Edward Barsky

- Varsovie Hospital

- Surgey at Varsovie

- Refugees

- Refugees

- Refugee Children

- Former PM José Giral

Here is a fragment featuring Dr. Barsky:

While Spain in Exile circulated among the Unitarian community, Rosenblum’s touching refugee portraits taken alongside the film crew reached a much wider audience through the New York Times, the New York Herald Tribune, the paper PM, and the popular weekly Liberty. Yet even this successful campaign involving film and photography did not serve to stem the negative effects of the HUAC investigation. As fundraising dwindled—both among the Unitarian congregations and the general public—government funds dried up as well. By 1948, the USC had cut its number of programs in half. By early 1949, Noel Field, who had left the USC in December 1947, mysteriously disappeared. In the course of the next three years, his name came up prominently in several spy trials in Hungary, East Germany, and Czechoslovakia.

In 1953, two prominent American Trotskyites, Nancy and Dwight MacDonald founded the Spanish Refugee Aid (SRA), devoted exclusively to aiding non-Communist refugees, whose fate, the MacDonalds felt, had been neglected for years. Two years later, the JAFRC dissolved itself, after Barsky had withdrawn from the organization following his release from prison.

Still, Barsky continued to be involved in progressive causes. In 1964 he was a founding member of the Medical Committee for Human Rights, which gave medical help to activists who joined in the struggle for civil rights in the US South. Later, he protested the war in Vietnam. He did not live to see the end of the dictatorship in Spain; he died nine months before Francisco Franco.

Sebastiaan Faber teaches at Oberlin College. This article draws on “Image Politics: U.S. Aid to the Spanish Republic and Its Refugees,” published in Forma: Revista d’estudis comparatius (Barcelona), no. 14 (2016).

Further Reading:

Anne-Emanuelle Birn and Theodore M. Brown, Comrades in Health: US Health Internationalism Abroad and at Home, Rutgers, 2013.

Peter N. Carroll, The Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, Stanford, 1994.

Phillip Deery, Red Apple: Communism and McCarthyism in Cold War New York, Oxford, 2016.

John Dittmer, The Good Doctors: The Medical Committee for Human Rights, Mississippi, 2017.

Reed Jenkins, “Edward K. Barsky: Surgery, Activism, and the Spanish Civil War,” Journal of Medical Biography, 2024.

Álvar Martínez Vidal (ed.). El Hospital Varsovia. Exilio, medicina y resistencia (1944-1950). Valencia: Afers, 2011.

James Neugass, War is Beautiful, New Press, 2008.

Eric R. Smith, American Relief Aid and the Spanish Civil War, Missouri, 2013.

Aelwen D. Wetherby. Private Aid, Political Activism: American Medical Relief to Spain and China, 1936–1949. Missouri, 2017.