A Giant of a Man: The Sacrifices of Edward Barsky

Self-effacing and shy though he was, Dr. Edward Barsky’s experience in Spain made him an outspoken activist, tireless organizer, innovative frontline surgeon, and political prisoner. “Eddie is a saint,” Hemingway wrote. “That’s where we put our saints in this country—in jail.”

Self-effacing and shy though he was, Dr. Edward Barsky’s experience in Spain made him an outspoken activist, tireless organizer, innovative frontline surgeon, and political prisoner. “Eddie is a saint,” Hemingway wrote. “That’s where we put our saints in this country—in jail.”

Edward K. Barsky was born in New York in 1895, attended Townsend Harris High School, and graduated from Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1919. He undertook postgraduate training in Europe and, on return, commenced an internship in 1921 at Beth Israel Hospital in New York, where he became Associate Surgeon in 1931 and where he established a flourishing practice. His father was also a surgeon at Beth Israel, and his two brothers, George and Arthur, also became doctors. Barsky’s private practice focused on industrial injuries and workers’ compensation cases that required surgery.

In 1935, Barsky, along with a great many other New York Jews, joined the Communist Party of the USA. This profoundly shaped his outlook on developments in Europe. Fascism was then ascendant, but in Spain there was hope. When the pro-fascist army generals arose against the elected Republican government in July 1936, Barsky realized, like Orwell, that this was a state of affairs worth fighting for. As he told a reporter, “I came to Spain for very simple reasons. Nothing complicated. As an American I could not stand by and see a fellow democracy kicked around by Mussolini and Hitler…I wanted to help Republican Spain.”

As casualties mounted, Barsky acted. In October 1936, he founded the American Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy. After frantically fundraising and then collecting, storing, and loading provisions to equip an entire hospital in Spain, Barsky—along with sixteen doctors, nurses, and ambulance drivers—sailed for Spain on January 16, 1937. This was just three weeks after the first American volunteers of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade had departed.

Barsky assumed control of the medical service within the International Brigade and his contributions and initiatives were significant. He established and headed seven front-line, evacuation, and base hospitals; refined the operating techniques of medical surgery under fire; pioneered a surgical procedure for removing bullets and shrapnel from chest wounds; and helped create the mobile surgical hospital that became a model for the U.S. Army in World War II.

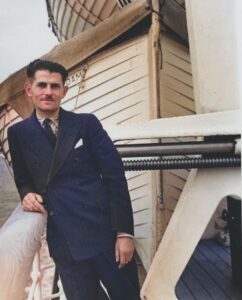

American Medical Bureau: Sailing on the SS Paris 16/01/1937. back row left: Mildred Rackley, Taos, New Mexico; Dr. Nathan Bloom, New York; Dr. Albert Byrne, San Francisco; Dr. Edward Barsky, New York; Dr. Edwardo Odio y Perez, Havana, Cuba; Harry Wilkes, New York; Dr. Phil Goland, Cincinnati; and Helen Freeman, Brooklyn, N.Y. front row left: Lini Fuhr Paterson, N.J. Salaria Kea, New York; Frederica Martin, New York; Ray Harris, New York; Anna Taft, Brooklyn, N.Y.; and Rose Freed, New York.

In July 1937 he took a brief leave from the front lines, to return to New York to raise funds for more medical aid. He addressed 20,000 at a rally in Madison Square Garden. When he returned (and he stayed in Spain until October 1938), he was made an honorary major in the Spanish Republican Army. In 1944 he wrote the autobiographical 302-page Surgeon Goes to War, which captures his deep commitment to and empathy with the Spanish cause. When the celebrated author of Citizen Tom Paine, Howard Fast, first met Barsky in late 1945, he described him as “a lean, hawklike man, handsome, commanding, evocative in appearance of Humphrey Bogart, a heroic figure who was already a legend.” According to Fast, he was “a giant of a man, tempered out of steel, yet quiet and humble.”

The Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee

From various organizations (United American Spanish Aid Committee, American Committee to Save Refugees and American Rescue Ship Mission) and individuals (especially veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade) that supported the Spanish Republic during the civil war, the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee (JAFRC) was born on March 11, 1942. The driving force was Barsky. With the Loyalists’ defeat in 1939, an exodus of more than 500,000 Republican Spanish refugees spilled over the Pyrenees into France. Most congregated in overcrowded refugee camps and then, from 1940 after the German occupation, were conscripted as laborers or sent to concentration camps. Thousands died in the Mauthausen camp. Thirty thousand were interned in North Africa. Eighteen thousand who escaped incarceration fought alongside the French Resistance (as well as de Gaulle’s Free French in Algeria). Some remained in Franco’s Spain, underground, attempting to avoid imprisonment or death. Others escaped to Spanish-speaking countries: Mexico, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic.

In the immediate aftermath of the civil war, Barsky—with his direct experience behind him but his visceral attachment to Spain intact—became preoccupied with the plight of these Spanish refugees. This preoccupation led directly to the establishment of the JAFRC, and the refugees were its raison d’être. Under Barsky’s indefatigable leadership, the JAFRC acquired legitimacy during World War II. Licensed to provide aid by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s War Relief Control Board, it was granted tax-exempt status by the Treasury Department. The committee raised funds, formed sixteen chapters in major American cities, established orphanages, and strenuously opposed Franco’s regime. As Barsky told dinner guests at the opening of the Spanish Refugee Appeal, which sought to raise $750,000, in March 1945: “Our program consists of relief, rehabilitation, medical care, transportation and associated welfare services, in many parts of the world. . . . Who will help [the refugees]? We! We are the only people to help them. We help them or they die.”

The Spanish Refugee Appeal sent thousands of dollars and tons of food, clothing, and medicines to Spanish refugees in both France and North Africa. The Unitarian Service Committee and the American Friends Service Committee, the latter a Quaker organization, distributed this relief on behalf of the JAFRC. An examination of the records of the Unitarian Service Committee reveals the very close working relationship with the JAFRC and the devotion of both to assisting refugees. The extensive correspondence dating back to 1941 does not contain a whiff of “communist front” about it. Instead, as one report later noted, the work of the JAFRC “was a work of mercy; it sheltered the homeless, fed the hungry, healed the sick.” Material and legal support was given to other refugees to emigrate to one of the few countries that welcomed them—Mexico. There, a school for refugee children was built and the Edward K. Barsky Sanatorium was opened when the JAFRC collected $50,000 after a national fundraising campaign in January 1945.

HUAC

On May 4, 1949, Barsky received some good news. His reappointment as surgeon at Beth Israel hospital, where he had worked since 1923, had been confirmed for another two years. Twelve months later, he received some disturbing news, and his life was changed irrevocably. He learnt that the Supreme Court had upheld a decision that he should serve a six-month sentence in a federal penitentiary. Upon his release, he learnt that his license to practice medicine would be revoked. These misfortunes had nothing to do with medical malpractice or professional incompetence. On the contrary, he was widely respected and trusted by patients, colleagues and hospital administrators. Instead, Barsky was paying the heavy price for a political decision he made in 1945—that, as chairman of the JAFRC, he would not cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). It was a fateful decision. He did not know it then, but for Eddie Barsky, the Cold War at home had started.

The JAFRC was the first to be subpoenaed by HUAC, the first to challenge HUAC’s legitimacy, and the first to set the pattern for Cold War inquisitions. In 1950, after three years of unsuccessful legal appeals, the JAFRC’s entire executive board was jailed. Coming before the Hollywood Ten trial and the Smith Act prosecutions, this mass political incarceration was the first since the Palmer Raids nearly thirty years before and the biggest during the McCarthy era. Barsky received the most severe sentence.

Upon release, Barsky lost his right to practice medicine. By early 1955, the JAFRC had dissolved: Like Barsky’s career, it had been crippled by McCarthyism. The actions against Barsky and the JAFRC were a historical marker. They signaled the first flexing of political muscle by HUAC, which saw its confrontation with JAFRC as a litmus test of its legitimacy. Because HUAC, not the JAFRC, triumphed, the framework was established for future congressional inquisitions that were to become such an emblematic feature of McCarthyism. What follows is an outline of how a once-flourishing medical career was thwarted and a once-viable organization was destroyed.

Persecution

HUAC subpoenaed Barsky and the JAFRC’s stalwart administrative secretary, Helen Reid Bryan, to appear before it in Washington on December 19, 1945. They were to “produce all books, ledgers, records, and papers relating to the receipt and disbursement of money” by the JAFRC, together with “all correspondence and memoranda of communications by any means whatsoever with persons in foreign countries.” On December 1, HUAC had requested the president’s War Control Board to cancel the JAFRC’s license to collect and distribute funds for the relief of Spanish refugees in Europe. The executive board held a special meeting on December 14 and unanimously adopted a resolution “to protect the rights of this Committee and its supporters” from HUAC. It would not surrender its records. In early January 1946, Barsky wrote to all contributors explaining the position of the JAFRC executive board. He cited a recent speech by Congressman Ellis Patterson (D.-Calif.), who called for the dissolution of HUAC, describing it as a “sham” that “violated every concept of American democracy.” That a showdown with HUAC loomed was implied by Barsky’s concluding remarks: The JAFRC was “determined to continue its humanitarian and relief work” and would “let nothing stand in the way of providing this aid.”

Why did HUAC swoop on Barsky and the JAFRC? There were several reasons, best encapsulated by Congressman Karl Mundt’s argument that the JAFRC was engaged not merely in disseminating un-American, anti-Franco propaganda but also in “secret and nefarious activities.” FBI files confirm that, by 1944, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover believed that the JAFRC was actually subversive. He was convinced, by two different “confidential” sources, that veterans of the closely associated Abraham Lincoln Brigade, who had been trained in military warfare, would “lead the vanguard of the revolution in this country.” Funds raised by the JAFRC, ostensibly for Spaniards’ relief, would assist that goal. Given the symbiotic relationship between the FBI and HUAC (in February 1946, a conference of senior FBI officials resolved to provide covert support to HUAC), it is probable that underpinning HUAC’s postwar harassment of the JAFRC was Hoover’s longstanding anticommunist crusade.

The closed executive session of HUAC that interrogated Barsky began on February 13. Barsky was not one whom HUAC could easily intimidate. Dressed in his “impeccably-clad double-breasted suit” and with his “business-like manner,” there was a “sureness about his manner, his talk, his gestures.” Throughout the hearings, he retained his dignity. Some HUAC members did not. Even at a distance of nearly eighty years, their rudeness, intimidation, capriciousness, and sheer bullying during these closed congressional hearings astonishes and shocks the reader of the transcripts.

Although Barsky wrote individually signed letters, twice, to every congressman, the only correspondence he provided to HUAC, upon request, was the names and addresses of all executive board members. This enabled the next round in the congressional committee’s offensive against the JAFRC. On March 16, 1946, every member of the executive board (in addition to Bryan and Barsky) was cited for contempt of Congress. Astonishingly, none of these individuals had been subpoenaed, none had appeared before HUAC, and none was given any opportunity to answer any questions.

This made no difference to members of HUAC. To Mundt, the JAFRC was “honeycombed” with communists, was “bringing foreigners to America,” and was “trying to destroy the things for which our flag stands”; to J. Parnell Thomas, the JAFRC was “a vehicle used by the Communist Party and the world Communist movement to force political, diplomatic, and economic disunity.” The JAFRC had become the enemy within. John Rankin hoped that the House of Representatives would “support the committee and let the world know that we are going to protect this country from destruction at the hands of the enemies within our gates.” The House complied. By a staggering majority, 339 to 4, the House voted in favor of citing Barsky for contempt of Congress.

Thereafter, all remaining sixteen executive board members were served with subpoenas. All appeared before HUAC, all refused to hand over any books or records, and all were cited. Legal representation was denied. Once again, the proceedings became aggressive. Recalcitrance was met with truculence. When the soft-spoken Professor Lyman Bradley was interrogated, a report noted, HUAC members “were exceedingly abusive in language and demeanor.” The congressional confirmation of this mass contempt citation in April 1947 resulted in the House of Representatives voting 292 in favor, 56 against, and 82 abstentions.

Twelve months passed before the U.S. District Court of the District of Columbia, on March 31, 1947, heard the indictment initiated by Justice Department prosecutors. The board was charged with “having conspired to defraud the United States by preventing the Congressional Committee from obtaining the records.” This changed a misdemeanor (contempt) into a felony (conspiracy) and thereby jeopardized the license to practice of doctors and lawyers (both well represented on the JAFRC board). When appealing for funds to cover immediate legal expenses Barsky rightly wrote that “This case against us is a potential threat to the civil liberties of all Americans.”

On June 16, 1947, the eighteen executive board members of the JAFRC were brought to trial in the Federal District Court of Washington. Eleven days later, the federal court jury convicted all eighteen board members of contempt. Immediately after the guilty verdict, five defendants got cold feet. They “purged” their contempt by recanting and resigning from the JAFRC board. Their sentences were suspended. The remainder, except Barsky, were sentenced to jail for three months and fined $500 each; Barsky received a six-month sentence. He received hundreds of letters of support, from Pablo Picasso in France to this unknown woman in Milwaukee: “My heart is sad by your suffering. I only wish I could give more. All the money I have to give is in this envelope. I gladly give my widow’s mite.” The thirteen convicted JAFRC members served notices of appeal and released on bond, but their drawn-out appeals were unsuccessful and three years later were incarcerated.

Imprisonment

On the day the board members commenced their jail sentences, June 7, 1950, a solitary line of about fifty veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade marched outside the White House. Their placards read “No Jail for Franco’s Foes” and “Franco was Hitler’s Pal.” A more “respectable” protest to the president was made by Francis Fisher Kane, an “old member of the Philadelphia Bar” and U.S. Attorney General under Woodrow Wilson. He “earnestly” requested that Truman commute the sentences imposed, because imprisonment was “a denial of justice and a blot upon American liberty.” Washington prison authorities, meanwhile, were itemizing the clothes of their new inmates—in Barsky’s case, a green hat, blue shirt, gray and yellow necktie, and brown pants and coat. He became Prisoner No. 18907. Ernest Hemingway (who met Barsky in Spain) transfigured him into a martyr: “Eddie is a saint. That’s where we put our saints in this country—in jail.”

The thirteen prisoners came from a range of backgrounds—academic, legal, literary, medical, labor union, and business. Initially, the male detainees were confined to the District of Columbia prison in Washington. The female board members were sent to the Federal Penitentiary for Women at Alderston, West Virginia. They were treated no different from the common criminal: handcuffed, stripped, processed naked, fingerprinted twice, showered, given faded blue uniforms, and locked in a shared cell five by seven feet in a towering prison block. After nine days, the men were deliberately scattered, being sent to Connecticut, Kentucky and West Virginia.

Barsky was sent to an isolated penitentiary, the Federal Reformatory in Petersburg, Virginia, 400 miles from New York. There, he lost twenty-five pounds, suffered from ulcers, was permitted only two visiting hours per month from his wife only, and was not permitted to do any medical work, only menial work. Coupled with the psychological strain of the past four years of criminal and civil litigations and appeals, his months in this remote jail would have tested his resilience. He would also have been concerned by the financial effects on his dependent wife, Vita, and two-year-old daughter, Angela, of his prolonged cessation of income. According to his lawyer, they “suffered extreme hardship during his incarceration.” Because of his regular and substantial donations to the Spanish Refugee Appeal, Barsky’s family had no reservoir of savings on which to draw.

A heartfelt, handwritten, two-page letter was sent to him from an acquaintance (“I don’t know if you remember me”), Samuel Anderman. The letter is worth noting because it illustrates how the persecution of Barsky touched a great many Americans unconnected with the JAFRC. After telling Barsky that his jailing had had a “profound effect” on him, Anderman continued: “There are many people like myself around, who are not sleeping easily while you and other patriotic Americans are being jailed. . . . Be of good cheer. This period is a severe trial but every great man has had to suffer for his convictions. Your suffering is not in vain.”

Barsky was freed from Petersburg on November 7. He was in time to both greet and say farewell to his loyal, steadfast secretary, Helen Bryan, as she began her three-month sentence on November 13. The night before, 200 friends, including Barsky, attended her farewell party at Fairfax Hall in New York. It was the final function he attended as JAFRC chairman. He resigned as officer, director, and member of the JAFRC in January 1951.

It could not have been easy for Barsky to relinquish the organization he had founded nearly a decade earlier. It was pivotal to his existence. According to a JAFRC staffer, “We never saw anybody with such single-mindedness. His entire life is wrapped up in the work of helping the refuges, in helping Spain.” He himself told a reporter: “Best committee in America. No committee in America has this tradition.” The reporter noted that it was near-impossible to get Barsky off the subject of the work of the JAFRC, about which he slipped into “lyricism.”

License Lost

If he thought deprivation of freedom would end upon his release from jail, Barsky was wrong. Another round of harassment commenced; another fight to resist it became necessary. It concerned not his political or humanitarian activities for the JAFRC, although these continued to stalk him, but his right to practice medicine. And it did not end until 1955, by which time the JAFRC announced its own dissolution. During his time in Petersburg penitentiary, Barsky’s medical license was revoked. The expectation was that restoration would be a formality.

At the hearing of the powerful Board of Regents, which decided his fate, the Assistant Attorney General of the state of New York, Sidney Tartikoff (for the Board), focused on the “communist front” activities of the JAFRC, the contempt of Congress citation, the constitutionality of HUAC, and, especially, the Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations that included the JAFRC. None of these issues, for which Barsky had endured five months in prison and five years of litigation, was relevant to medical competence. None of these issues involved “moral turpitude,” the customary concern of the Board. None of the dozens of testimonials counted. Barsky was found guilty of nothing, other than his failure to produce records subpoenaed by a congressional committee. The Board revoked Edward Barsky’s medical registration, first issued in 1919, for a period of six months. No reasons were given. Subsequent appeals were all unsuccessful, and on June 25, 1954, the suspension of Barsky’s medical license took effect.

Eventually, Barsky picked up the threads of his practice. Unlike the organization he founded and to which he was utterly devoted, Barsky survived. McCarthyism, which had so deeply gouged the American political landscape, was waning. Barsky continued to support progressive causes, especially civil rights and the peace movement. He was involved in a strike at Beth Israel Hospital in 1962, organized by Local 1199, over recognition of union membership of hospital employees. Two years later, he helped establish the Medical Committee for Human Rights. It provided doctors and medical staff for civil rights activists who went to Mississippi in the violent “Freedom Summer” of 1964. He remained active in this committee as well as in the anti–Vietnam War movement. He died at the age of seventy-eight, on 11 February 1975.

Edward K. Barky was a self-effacing man. According to his daughter, he was a “very private, a shy man who did not toot his own horn.” Never given to effusive displays or the grand gesture, he was motivated by compassion and ideology, not the limelight, when he went to Spain and later supported Spanish refugees. He would have been uncomfortable, yet gratified, when seven ambulances sent in 1985 from the US to Nicaragua in 1985 in support of the Sandinistas were named in his honor. Howard Fast was right: he was a giant of a man.

Phillip Deery is Emeritus Professor of History at Victoria University, Melbourne. He has written about communism, espionage, the Cold War, and the labor movement. His latest book is Spies and Sparrows: ASIO and the Cold War. This article draws on Red Apple: Communism and McCarthyism in Cold War New York (2014).