Nehru and the Spanish Civil War

Jawaharlal Nehru in Spain during the Civil War, with the Catalan President Lluís Companys (r) and Bhicoo Batlivala, the Parsi lawyer and Indian independence campaigner.

Why did Jawaharlal Nehru, future prime minister of India, visit civil-war Spain in 1938? As it turned out, the triangular relationship between Britain, Spain, and India had deep cultural and geopolitical implications.

As collectors well know, the extant copies of the Book of the XV Brigade, a richly illustrated volume edited by Frank Ryan that was distributed among hundreds of English-speaking brigadistas in 1938, are considered bibliophile gems because they are often hand-signed by dozens of fellow soldiers. The copy held at the Working-Class Movement Library in Salford, England, however, features two surprising autographs: from Jawaharlal Nehru, who in 1947 would become the first Prime Minister of India, and V. K. Krishna Menon, India’s representative to the United Nations and founder of the Non-Aligned Movement. They signed the book during a visit to Spain in June 1938, where Nehru and rest of the Indian delegation met with the British Battalion of the XV International Brigade—which, as it happened, was named after Shapurji Saklatvala, the Bombay Parsi who served as MP for North Battersea, first for the Labour Party and later as a Communist.

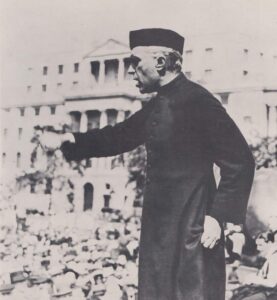

Nehru addresses a meeting at Trafalgar Square, London, in support of the Spanish Republic, July 17, 1938. Nehru Memorial Fund.

What was Nehru doing in Spain, when there was so much to campaign for in British-ruled India? The truth is that the Spanish Republican cause attracted many Indian intellectuals in both Britain and the subcontinent. While the cultural ties between Spain and India go back centuries—from colonizers and missionaries to the musical roots of flamenco—in the early twentieth century, the triangular relationship between Britain, Spain, and India, with Gibraltar as a gateway to the East, had deep cultural and geopolitical implications.

Saklatvala’s had been a rare Indian voice in Britain’s parliament. He was only the third Indian representative in parliamentary history and the country’s lone Communist MP, winning a re-election for his seat for the CPGB after Labour expelled all Communists from their party in 1923. Saklatvala had died from a heart attack in January 1936; his daughter, Sehri Saklatvala, organized events for the Spain-India Committee, run by the India League.

By the 1930s, the British Left was quite transnational and included many anti-colonialists protesting the British Empire. In London, Indian activists organized aid for Ethiopia, China and Spain. Indians in Britain also took part in the India Home Rule Society, India League, League Against Imperialism, Independent Labour Party, Communist Party, Workers Welfare League, and myriad other organisations. As Nancy Tsou and Len Tsou have shown in Los brigadistas chinos en la Guerra Civil: La llamada de España (1936-1939), some Indians joined the brigades as doctors, journalists and soldiers, including Gopal Mukund Huddar, Mulk Raj Anand, Atal Menhanlal, Ayub Ahmed Khan Naqshbandi, Manuel Pinto, and Ramasamy Veerapan.

Nehru and his daughter, future Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, saw themselves as part of both British and Indian society. Educated at Harrow, Nehru later joked that he was the “last Englishman to rule India.” In his book Anti-Colonialism and the Crises of Interwar Fascism, Michael Ortiz discovers that Indira, educated at Badminton School in Bristol and later Oxford, was especially preoccupied with the fate of the Basque orphans. In fact, the traffic between British colonial officers and later Indian anti-colonial leaders was two-way. The most famous British author of the Spanish Civil War, George Orwell (Eric Blair), was, after all, born in Motihari, India.

According to Richard Baxell, the British Battalion’s official name, Saklatvala, “never caught on.” Naming an IB Battalion after Abraham Lincoln worked well in the US context. Though a prominent MP, Saklatvala did not have that kind of legendary historical reputation, and his name might well have been harder to pronounce for many volunteers. Nor was there a settled view on Britain’s ongoing rule of India. (Nehru and Saklatvala certainly had their differences: Nehru was not a Communist like ‘Comrade Sak’ who protested Gandhi’s absolute insistence on nonviolent resistance.) Most referred to the Saklatvala as the “British Battalion” while most Spaniards simply called it “el batallón inglés.” As Baxell points out, this was not a very satisfactory name for a unit that included many non-English soldiers—not only Irish, but also volunteers from many current or former British colonies. In fact, when Nehru, Krishna Menon and Batlivala visited the British volunteers they were greeted by cries of “Long Live Independence!”.

Nehru’s interest in Spain was not surprising. By 1936, he had grown frustrated with Gandhi’s leadership of the Indian independence movement. As he mourned the death of his wife and struggled to manage the splintered Congress movement, he considered resigning as president of the Congress. But then, as he writes in his autobiography, “a far-away occurrence … affected me greatly … This was the news of General Franco’s revolt in Spain. I saw this rising, with its background of German and Italian assistance, developing into a European or even a world conflict.”

Nehru was one of many Indian intellectuals drawn to the Republican cause, as were Bengali Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore and Telegu poet Srirangam Srinivasarao. (Tagore’s global fame had reached Spanish poets such as Zenobia Camprubí and Juan Ramón Jiménez, who translated his work.) Cultural affinities, such as the possible influences of ancient Indian dance styles on flamenco drew interest about Spain from Indian artists and intellectuals.

There were also political parallels. The Indian Congress and Spanish Second Republic shared goals in the 1930s, such as tackling illiteracy and the problem of large and unproductive agricultural estates. As Maria Framke writes, Congress Socialists organized a “Spain day in different Indian cities in August 1936” and in December of that year asserted at their annual meeting that “this struggle between democratic progress and Fascist reaction is of great consequence to the future of the world and will affect the future of imperialism and India.” Ole Birk Laursen describes a major protest in January 1938, on Trafalgar Square in London, in solidarity with the Indian, Chinese and Spanish people:

As around 1,200 people marched from Mornington Crescent, “four bands accompanied the processionists. Flags of the Spanish Republic, Irish Republic, Indian National Congress and Sama Samaja Party, and banners with portraits of Subhas Chandra Bose, Jawaharlal Nehru, Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, the Emperor of Abyssinia, Chiang Kai-Shek, and ‘La Pasionaria’ (the Spanish woman communist leader), were carried.

The British Library India Office Records shows that British intelligence was concerned by Nehru’s trip, actively tracking his departure from London to Barcelona, and reporting in great detail on every speech Nehru made once he returned to London. British authorities were worried by the ability of Nehru, and other speakers in London such as Paul Robeson, to synthesize a broader anti-imperialist movement and connect it with what authorities considered a dangerously Communist anti-fascism in Spain.

Nehru’s five-day visit to Spain in June 1938 was widely reported in newspapers worldwide. His “tight schedule” included meetings with President Manuel Azaña, Foreign Minister Julio Álvarez del Vayo, Communist leader Dolores Ibárurri, receptions with “the Cortes, the national Parliament,” the Foreign Ministry, and, at the battlefront, with officers from the Republican Army and the International Brigades. Photographs of Nehru with Spanish Republican generals and politicians underscore the friendship between the Spanish and Indian peoples; but there was also a geopolitical and pragmatic calculus in Nehru’s decision to go to Spain.

After his return from Barcelona, Nehru addressed a 5000-strong crowd in Trafalgar Square, during an event organized under the auspices of the Aid to Spain Committee. Still, Nehru also faced criticism for his trip. Why was he touring around Europe and agitating for Spain when there were flood victims in Bengal and widespread famine around the country? In The Manchester Guardian and The National Herald (the newspaper Nehru founded in Lucknow), Nehru responded to his critics in a text that was later published as a pamphlet, Spain! Why? (1938), by the India League. In it, Nehru defends himself against those who see him as naïve. Since the British government is effectively aligned with Fascists, he argues, supporting the Spanish Republican cause is an act of anti-colonial resistance:

By sending a Medical Mission to China, by our giving food-stuffs to the Spanish people, we compel the world’s attention to our view-point. Thereby we begin to function in the international sphere and the voice of India begins to be heard in the councils of the nations. This is our way of building up a foreign policy and of giving effect to it. Thus, our giving practical shape to our sympathies has a vital significance in giving India a position and prestige which usually only free countries possess. …. The free aid that we give medically or otherwise to China and Spain stamps us as people who have a view and will of their own.

As Michael Ortiz has pointed out, moreover, for Nehru the Spanish Civil War “underscored the hypocrisy of Britain”:

During the Waziristan Campaign (1936–1939), British colonial forces brutally quashed the Waziri and Mahsud tribesmen of Waziristan. Only months after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, local Waziri led by the Fakir of Ipi opened fire on British Colonial forces in a valley just outside Bichhe Kashkai. To reassert colonial hegemony, British forces bombed the Waziri. How, Nehru argued, could English citizens condemn the bombing of Guernica while ignoring a similar tragedy in Afghanistan?

While other Indian campaigners for independence such as including Mulk Raj Anand and V. Krishna Menon openly compared British colonial rule with German and Italian fascism, Nehru and the Congress movement did not directly challenge the patently undemocratic British Empire. Still, Nehru’s comparison of the bombings of the Waziri with those of Guernica shows he was certainly able to make the comparison between British colonial rule and German and Italian fascism. The overwhelming majority of the British Empire’s subjects lived in a dictatorship backed by the same imperial navy that blockaded aid from the Soviet Union and Mexico from reaching Republican Spain.

The images of Nehru’s visit, and his report on it in his memoirs, gloss over some of the contradictions involved in supporting the Spanish Republican side, let alone calling for British intervention in Spain. For one, the Spanish Republic itself continued to be a colonizing power in Morocco, Western Sahara, and Equatorial Guinea. For another, calling for British intervention in Spain meant advocating for Britain to use its imperial might: in particular, the very same navy that patrolled India, often with colonial troops, sepoys, in its ranks. Ortiz notes that “during Nehru’s visit, British machine gunners put on a thrilling display with their maxim gun”; from Richard Baxell, we know that the commander of the Machine-Gun company was “Harold Fry, an ex-sergeant from the British army who had served in India and China.” Did Britain’s many machine gun atrocities such as the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919 occur to Nehru in this moment?

Michael Ortiz suggests that Nehru found his visit to the British Battalion refreshing after years of Gandhi’s doctrine of non-violence. Jim Jump, a British volunteer who served as Nehru’s translator, wrote about the visit in his memoir, The Fighter Fell in Love, recently published by the Clapton Press:

Nehru spent quite a long time in the barranco, chatting to us. He displayed great interest, despite being a pacifist, in our machine guns, and the gun-crew, led by ex-miner from Fife, George Jackson, put on an exhibition of accurate firing. With a few short bursts of fire from their First World War Maxim, they chopped down a sapling growing a couple of hundred yards away. ‘Would you like to have a try yourself?’ Jackson asked him, but Nehru politely refused.

Like it did for the African American volunteers, Spain provided a release for oppressed dissidents from elsewhere in the world who were militarily outmatched at home or tired of demands for only nonviolent civil disobedience. In Spain, they had a way of striking back at the enemy, arms in hand, even in the knowledge of the contradictions involved in supporting the Republican side.

Considering the tensions between pacifism and armed struggle, and between anti-fascism and empire, naming the British Battalion after Saklatvala was quite appropriate. As Priyamvada Gopal explains, Saklatavala was a thorn in Mahatma Gandhi’s campaign for non-violence, arguing against a pacifist position. Their correspondence shows a revolutionary Saklatvala seeking to radicalize the liberal Gandhi towards a position that would require both nonviolent and violent resistance.

A gunner company in the Saklatvala Battalion was named after Clement Attlee, the Labour MP who made several visits to Spain and features in significant images from the war, including photographs with Guernica at The Whitechapel Gallery in London. Attlee became Prime Minister in 1945. It was his government that granted India independence. Yet, to the disappointment of many IB volunteers from Britain and India, it made no move to depose Franco.

Ameya Tripathi is Assistant Professor of Modern and Contemporary Spanish Literatures and Cultures at New York University. He is working on a book project on documentary writing, photography, radio and film in the Spanish Civil War. With thanks to Jim Jump and Richard Baxell for their research help for this piece.