Her Most Heart-Felt Cause: Martha Gellhorn and Spain

EH 2981P Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn during the Spanish Civil War, c.1937-1938. Photograph in the Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

The time she spent in civil-war Spain loomed large in the life of Martha Gellhorn, the St. Louis-born war journalist. “The truth is that Martha could not stop thinking, feeling, and writing about her Spanish experiences.”

“Objectivity bullshit.” That’s what Martha Gellhorn (1908-1998) called the journalism of her day. Her letters to personalities like Eleanor Roosevelt, H. G. Wells, John Dos Passos and of course Ernest Hemingway, her companion, lover and husband in the 1930s and 1940s, were anything but measured. Gellhorn—an American journalist, novelist, antifascist, and defender of the victims of war, especially children—was not known for mincing words.

Although she was among the most audaciously progressive voices of those years, she was not the only writer who yearned to go beyond “objective” and “impartial” reporting. Together with many of the authors gathered at the 1935 Writers Congress, she sought to redefine political engagement. But this does not mean that her work was propaganda. The fact that Gellhorn did not hold back did not mean she hid her dilemmas, doubts, or contradictory emotions.

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, she grew up in a posh neighborhood on McPherson Street to which she often returned throughout her life. Her father, George, was a German-born gynecologist; her mother, Edna, the daughter of a professor of medicine and well-known for her activism for women’s suffrage. Edna was a graduate of Bryn Mawr, where she had met Eleanor Roosevelt, who would remain a close friend of the Gellhorn family. It is clear from her letters that Martha adored and admired her mother, not only for her affection for her four children, but also for her exemplary courage and activism. In 1916, Edna brought an eight-year-old Martha to a demonstration she had organized for women’s rights.

For Martha, the contradiction between her egalitarian ideas and her socio-economic privileges caused her considerable anguish, an anxiety manifested itself in virtually all her writing. Following her mother’s advice, she enrolled at Bryn Mawr but was uneasy about her status as a well-to-do student. After dropping out of college, she landed a job as a reporter for the Albany Times Union. But being a small-time reporter was equally unsatisfying, especially when the editor did not publish what she believed her most engaging writing, such as the story of a woman who lost custody of her daughter for smoking during her working hours. She left the paper, returned home, and dedicated herself to writing without objections or censorship. But life in St. Louis bored her. Her letters in this stage of her life manifested the restlessness of a sophisticated, energetic, spoiled woman who abhors the provincialism of her surroundings. What she yearned for could only be found in Europe. With the tacit approval of her parents and about five hundred dollars, she set off for the “City of Light.”

In Paris she worked first in a beauty salon and then as a reader for magazines and newspapers, sometimes editing advertisements. But even here in the city of modernist culture—where she coincided with Picasso, Buñuel, Cocteau, and Josephine Baker, a newcomer to Paris who sang and danced in the fashionable cabarets—she could not express her creativity, until she met the man who helped her launch her literary career, the writer and philosopher, Bertrand de Jouvenel, who fell in love with her.

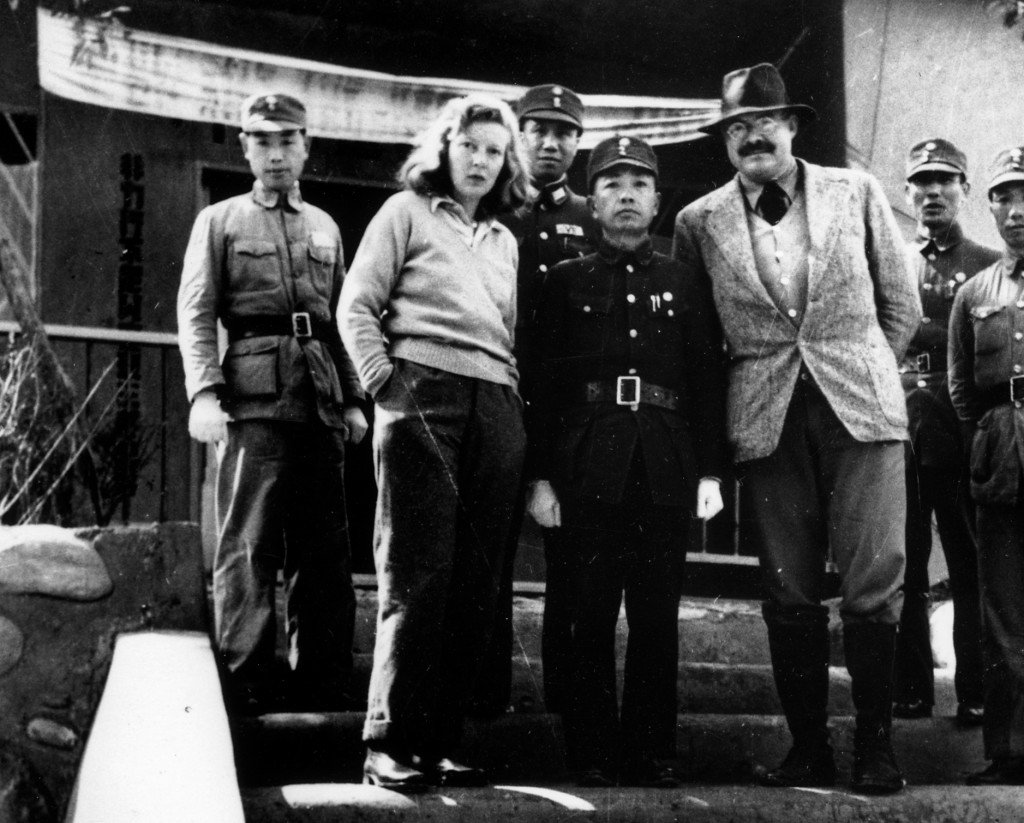

Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway with unidentified Chinese military officers, Chongqing, China, 1941. JFK Presidential Library. Public domain.

It is clear from her letters that she loved him, less for his physical and emotional attraction than for being a prominent man with advanced ideas—a philosopher, a connoisseur of economic policy, a liberal activist and scholar of fascism, an ideology that was sweeping Europe. Hitler and Mussolini were on the rise, leading a violent movement that sought to crush the democratic principles to which Jouvenel, Gellhorn, and others aspired. Indeed, from the beginning to the end of her life, Martha did everything she could as a writer to build not only the idea of democracy but the practice of it, working tirelessly for children, women, workers, ordinary people with whom she interacted on a daily basis.

Principles were not enough for her. More than her romantic relationships, more than the fascination and intellectual curiosity, Martha’s longed to become a journalist and novelist. She wrote constantly. Among her early works is a collection of four short stories, The Trouble I’ve Seen, in which she portrays the sorrows she had witnessed. The book included a celebrated short piece, “Justice at Night,” about a lynching, drawn from her travels through the South. Still, she constantly complained in her letters that her writings fell short due to the distractions that surrounded her: the relationship with Jouvenel (a married man whose wife was unwilling to divorce), the living conditions she witnessed, and the desire to change them. In 1934, as the relationship with Jouvenel faltered, she returned to St. Louis.

Back in the US, she got in touch with her mother’s friend in the White House, Eleanor Roosevelt, an energetic defender of the millions of Americans suffering from unemployment, hunger and misery. With the support of the Roosevelts, Martha joined the Federal Emergency Relief Agency (FERA) designed to provide economic aid to unemployed workers. She once encouraged some workers in the state of Idaho to throw rocks at the windows of the building housing the agency, which in her opinion did nothing to protect “those poor people.” She was fired, which she considered an honor.

The president’s wife admired Martha’s feistiness. Their fascinating correspondence discusses class inequality, the international threat to democracy, the power of trade unions, as well as personal issues such as love, motherhood, and books that had impressed the two women. Eleanor was something of a mother figure to Martha. The first lady wrote flattering comments about her in her celebrated syndicated column “My Day,” published six times a week in hundreds of newspapers and magazines around the country. About The Trouble I’ve Seen she wrote: “The writing of this woman, young, beautiful, literate, from a good family, with exquisite Parisian tastes and admirable spirit, cannot be underestimated.” From what we now know about Mrs. Roosevelt, and reading into their correspondence, her friendship with Martha may have gone farther than that, hidden in the closets of the White House.

After her father’s death in January 1936, Martha traveled with her family to Key West for a Christmas holiday, and there she met Hemingway, then the famous author of The Sun Also Rises and Farewell to Arms. It was at a bar where the novelist spent time carousing with other writers. Years later, Gellhorn insisted that her relationship with Hemingway was only one episode in her life, that it did not define her character, much less her writings. Beginning in the sixties and well through her life, she insisted on not talking about “Scrooby,” the nickname she coined for him. When journalists asked about her relationship with him, she refused to answer. She was fed up with the lack of attention to her abundant writings: essays, novels, short stories, chronicles of various wars she covered as a reporter. Still, it’s hard to deny that were it not for E.H., Martha’s life would have taken a different direction.

When Martha returned to St. Louis from Key West, she was eager to go to Spain. Hemingway, equally enamored of his new friend, was willing to accompany her to the war-torn nation. Hemingway would provide her with what she wanted: direct contact with the country, not as a tourist but as a writer/journalist. She needed to see the war with her own eyes, no matter the danger. In 1937, after obtaining an official designation from Colliers as a “special correspondent,” she joined him at the Hotel Florida in Madrid.

These are the years Martha wrote what are the best of her journalistic pieces. In Colliers in June 1937, “Only the Shells Whine,” there is no shortage of novelistic touches, metaphors, action, and graphic descriptions. “At first the shells went over: you could hear the thud as they left the fascist guns,” she writes. “As they came closer the sound went faster and straighter [until] you heard the great booming noise when they fell.” In another story covering the war, “Men without Medals” (January 1938), Gellhorn zeroes in on the men in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. It begins with a dialogue between the reporter and a “little soldier with pink cheeks, spectacles and a Brooklyn accent.” He shows her a grenade, asking: “Wanna see how it works?” “No, pal,” the reporter replies, “I believe you.” His fellow soldiers laugh at him as he tries to flirt with the beautiful journalist. One of them is Andy Anderson, the son of farmers from Nebraska, who has seen his comrades die at Belchite and is among the few “survivors of the first American battalion.” Gellhorn does not delve into historical or ideological facts; she prefers direct discourse to that “objectivity bullshit.” She is interested in the soldiers as human beings. Why did they cross the Pyrenees in the snow? Why don’t they give them veterans’ medals? Why are they insulted in their own country for sympathizing with communists? And why don’t Andy’s countrymen realize the emergency of the Spanish situation?

Surprisingly, Gellhorn never wrote any fiction set in Spain. As she states in several instances, she could not bring herself to do so while Hemingway was on his way to deliver For Whom the Bell Tolls. When in 1940 Gellhorn published her own novel about 1930s fascism, A Stricken Field, it was set in Czechoslovakia. Spain and the anti-fascist war was her most heart-felt cause, but perhaps that was precisely what made it too difficult to turn into a novel. She set her story elsewhere not to allow for objectivity but for distance. In A Stricken Field, the protagonist summarizes the instructions she got from her newspaper editors: “[Write] without propaganda, they told me. They wanted descriptions from within: clear, colorful, dynamic. But how? If I knew how, I would write a lament, I would tell how the children of Spain, in Barcelona, sang in that cold and windy month of March when the planes dropped bombs that fell with the speed of the wind for a few interminable moments…”

The truth is that Martha could not stop thinking, feeling, and writing about her Spanish experiences. Among the later writings on Francoist Spain is a piece she wrote for New York Magazine, on the death of the “generalísimo,” entitled “When Franco Died” (1976). On the same day of his death, she traveled to Madrid and stayed not at the Hotel Florida, which had already made way for a department store, but at the Palace Hotel, which was a hospital during the Civil War. As she walks around the hotel, Gellhorn observes, ever the journalist, that the same room where the television set is broadcasting images of Franco’s corpse while some ladies wipe away tears, is very same room that, years ago, housed half-dead soldiers of the Second Republic with amputated arms and legs. She remembers the smell of ether, stale food, and blood-spattered marble stairs. She also remembers Madrid in the winter of 1937, the day 275 bombs fell on the city, causing 32 dead and more than 200 seriously wounded. On the night of Franco’s funeral, she attends an illegal meeting organized by wives of political prisoners. “The wives were heartbreakingly optimistic,” she writes. “They expected the jails to empty in a fortnight.”

Everywhere, says Gellhorn, people are slowly beginning to take risks by speaking freely, although no one forgets that the only one who had died was Franco, not the policemen who were still very much alive and active. Let’s not forget, she continues, that the process known as the “transition” to democracy is more cosmetic than democratic. When Franco died, she goes on,the Civil Guard continued to commit acts of brutality, as in the case of an engineering student who had been beaten into a coma in the same hospital where the dictator had died. There were two forms of torture happening, she points out: the dying head of state whose final days seemed and the torture on the street carried out by agents of that same man.

During the Spanish transition Gellhorn was approaching seventy. Many would say that she had more than fulfilled her literary aspirations. After Spain and Czechoslovakia, she covered multiple wars: she wrote about World War II from Finland; she traveled to Hong Kong to cover the Chinese revolution, then to Singapore. She wrote about the Nuremberg trials, Jerusalem, and Eichmann’s testimony, the Israeli-Palestinian wars, U.S. military involvement in Vietnam, and the struggle for civil rights in the United States. But her writerly legacy does not only consist of journalistic pieces and reports of real events; she also produced narrative fiction. In addition to A Stricken Field, she wrote other novels, novellas, and short stories. (Her 1967 novel The Lowest Trees Have Tops, a story about the Red Scare, set in Mexico, is worthy of reconsideration.) She mused in her later correspondence to friends (the few that were left) that she could have written much more. At the age of ninety she died from what was probably, according to Moorehead, a suicide. She had always been determined to write her own script, without mincing words.

Author’s note: I am indebted to Caroline Moorehead, who in addition to writing a penetrating biography of Gellhorn and editing her Selected Letters, has generously replied to my emails.

Michael Ugarte is Professor Emeritus of Spanish at the University of Missouri. A longer version of this article appeared in Spanish in the online journal FronteraD.