Generalissimo Francisco Franco is Still Dead—Fifty Years Later

As SNL is preparing for its 50th anniversary, Tyler Goldberger speaks with Chevy Chase about his legendary gag on Franco’s death.

In the fall of 1975, the declining health of Francisco Franco, who had ruled Spain for 36 years, dominated the US news cycle. When Franco died on November 20, VP Nelson Rockefeller traveled to Spain to attend his funeral while former President Richard Nixon described him as a “loyal friend and ally of the United States.”

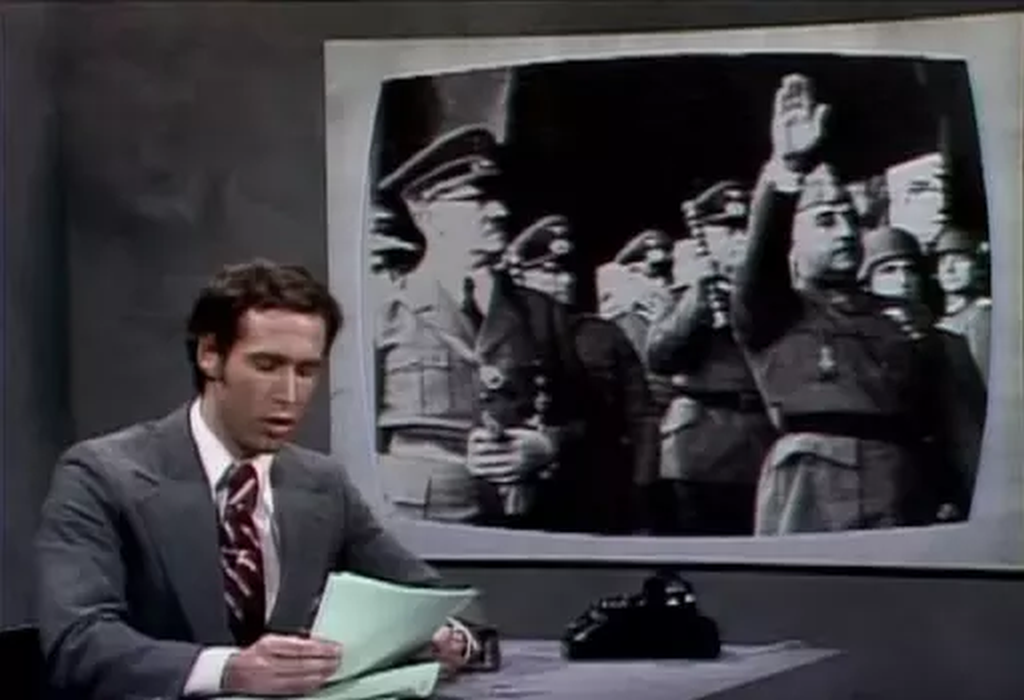

Nixon’s words were quoted mockingly that same week by Chevy Chase, who presented the Weekend Update on NBC’s Saturday Night, which was then in its first season. Chase contrasted Franco’s legacy as “the last of the fascist dictators in the West” with eulogies spoken by Western leaders. As Chevy recalled Nixon’s admiration of Franco’s “firmness and fairness,” the photograph behind him displayed Spanish leader doing a Heil Hitler salute right next to Adolf Hitler. The irony wrote itself. Throughout the first two seasons of the show, Chase would continue “reporting” on events in Spain as a running gag with endless variations on the punchline “Generalissimo Francisco Franco is still dead.”

I recently had the chance to sit down with Chevy Chase and his wife Jayni to look back on the iconic bit. As Chevy remembers it, once Franco died, “[The news] was everywhere.” While walking to the studio on November 22, 1975, as he noticed that every news stand was selling the headline of Franco’s death, he thought of a bit to emphasize that “everybody’s sick of seeing this.”

Jayni, who had just turned 18, has fond memories of watching the first season of Saturday Night and laughing with her friends about the sketch. Prior to us speaking, she asked a few people if they remembered the punchline “Generalissimo Francisco Franco is still dead. “They all “cracked up and… said absolutely,” she told me. Although she was unfamiliar with Franco at the time, watching Chevy’s sketch, she told me, made her think to herself: “Who is this guy?” Jayni believes that many Americans shared her experience. In other words, it was the SNL sketch that drew attention back to the political situation in Spain.

In the years following Franco’s 1939 victory in the Spanish war, the US administration considered him an adversary. But this shifted during the Cold War, when the US was eager to enlist Franco in the global fight against communism. The 1950s brought renewed friendship between the United States and Franco-Spain. The 1953 Pact of Madrid established military and economic ties between the two countries. Four military bases were built with American money in the decades following, in exchange for over $1 billion USD to support Spain’s dictatorship.

In December 1959, President Dwight D. Eisenhower became the first sitting president to visit Spain. Following an invitation from Franco, Eisenhower incorporated Spain into his eleven-nation goodwill trip before his second-term presidency ended. He was welcomed with open arms by Franco and the Spanish public, conducting a press conference next to the dictator in Torrejón de Ardoz, one of US military bases. He then participated in a parade down the center streets, which up to 1.5 million of Madrid’s 2 million inhabitants attended. The 1960s further deepened the connection between the two nations, as Spain worked diligently to pitch itself as a desirable destination for Western tourists.

I asked Chevy Chase what he knew about Franco in 1975. “I didn’t know shit,” he told me, beyond thinking of the dictator as a “brute” and “bad guy.” Still, his bits following the dictator’s death resonated with the historical memory of the Spanish Civil War, which had mobilized millions of Americans in the 1930s and convinced close to 3,000 of them to help defend the Spanish Republic in person.

Some of this historical memory still lingers today. Seminal texts such as Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls and George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia are still taught and read. Picasso’s Guernica hung in the halls of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City for almost four decades, as the painter refused to have this masterpiece displayed in a Franco Spain. After Spain passed its 2007 Historical Memory Law, which called for the removal Francoist monuments from public spaces, the Wall Street Journal coyly reported “Generalissimo Francisco Franco Is Still Dead—and His Statues Are Next.”

Tyler J. Goldberger is a History PhD candidate at William & Mary. His work explores U.S.-Spain relations in the 20th century, historical memory after civil wars and conflicts, human rights, and transnationalism.