Books Briefly Noted: Spain’s Many Postwars

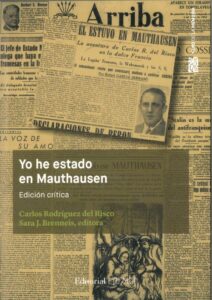

Carlos Rodríguez del Risco, Yo he estado en Mauthausen, edición crítica. Edited by Sara J. Brenneis. Cádiz: Editorial UCA, 2024. 304 pp.

Carlos Rodríguez del Risco, Yo he estado en Mauthausen, edición crítica. Edited by Sara J. Brenneis. Cádiz: Editorial UCA, 2024. 304 pp.

Carmen Moreno-Nuño, Haciendo Memoria: Confluencias entre la historia, la cultura y la memoria de la Guerra Civil en la España del siglo XXI. Madrid: Iberoamericana, 2019. 319 pp.

Recent years have seen a growing number of books about the complex legacies of the Spanish Civil War and World War II. What sets these two titles apart is their broad focus, as they place Spain and its efforts to deal with its recent history within a global conversation about coming to terms with twentieth-century violence.

Carlos Rodríguez del Risco’s diary Yo he estado en Mauthausen, edited by Sara J. Brenneis, shows why personal narratives have been so essential for deepening our understanding of World War II. Rodríguez was a Republican soldier who fled to France after Franco’s victory and fought the Nazis during World War II. After being imprisoned in a German concentration camp, he returned to Spain as a “Hitler apologist, fervent follower of Francisco Franco and a newly minted fervent fascist.” Still, his testimony is an early depiction of the horrors of Nazi concentration camps.

The diary and its initial serialized publication in the Falangista newspaper, Arriba, becomes in Brenneis’s excellent introduction a powerful example of the complex political maneuvering and accommodations, both conscious and unconscious, in the early years of the Franco regime. Brenneis, who has written key works on Spaniards in the German camps and also Spain’s memory battles in the twenty-first century, explains how and why Rodríguez del Risco became such a staunch paragon of Francoist Spain. It is a revealing story that explains the mechanisms of Francoist propaganda and the complexities of Spain’s current confrontation with the past.

Carmen Moreno-Nuño’s book Haciendo memoria asks the same broad questions of Spain’s unique memory landscape, but with a more direct scan of contemporary representations of the past in film, journalism, television, and literature. Wisely, Moreno-Nuño does not read works like Guillermo del Toro’s film The Devil’s Backbone (2001) as historical works per se, but as statements about how we want to remember the past, what we want to discover, what we might want to forget—all in service of contemporary political needs and desires.

Carmen Moreno-Nuño’s book Haciendo memoria asks the same broad questions of Spain’s unique memory landscape, but with a more direct scan of contemporary representations of the past in film, journalism, television, and literature. Wisely, Moreno-Nuño does not read works like Guillermo del Toro’s film The Devil’s Backbone (2001) as historical works per se, but as statements about how we want to remember the past, what we want to discover, what we might want to forget—all in service of contemporary political needs and desires.

Moreno-Nuño couches the particularities of Spanish memory in the early twenty-first century in a broad analysis of the ways global capitalism mobilizes the messy past—with its questions of guilt, complicity, collaboration, and atonement—to soften the ideologies of the past and present a quiescent and narrow set of political possibilities in today’s world. For Moreno-Nuño, some of the works featured in her book manage to widen this narrowed political worldview.

Both books make clear that Spain occupies a central place in the history and memory of twentieth-century wars. The legacy of Spain’s role in World War II is still deeply marked by Franco’s decades-long efforts to shape or suppress it. Attempts to confront that legacy are just now rising to the surface. The question these two books grapple with is whether Spain’s challenge is much different from those faced by any other country trying to come to terms with a war-torn past.

Joshua Goode, The Volunteer’s book review editor, is a professor of cultural studies and history at Claremont Graduate University.