Book Review: A Russian in the Blue Division

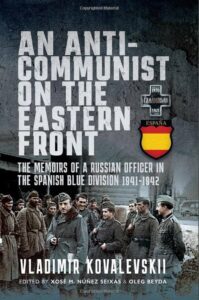

An Anti-Communist on the Eastern Front: The Memoirs of a Russian Officer in the Spanish Blue Division, 1941-1942, by Vladimir Kovalevskii, edited by Xosé Manoel Núñez Seixas and Oleg Beyda. Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military, 2023. vii + 249 pp.

An Anti-Communist on the Eastern Front: The Memoirs of a Russian Officer in the Spanish Blue Division, 1941-1942, by Vladimir Kovalevskii, edited by Xosé Manoel Núñez Seixas and Oleg Beyda. Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military, 2023. vii + 249 pp.

In An Anti-Communist on the Eastern Front, Xosé Manoel Núñez Seixas and Oleg Beyda reconstruct the scattered memoirs of Vladimir Kovalevskii, a White Russian volunteer soldier who led an adventurous life. After fighting against the Red Army in Russia’s bloody civil war (1917-1922), he enlisted with the French Foreign Legion, serving a number of years in North Africa before moving to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, most likely in the mid-1920s. Two years after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, he relocated to Spain to volunteer for Franco’s coup d’état against the Second Spanish Republic, along with a handful of other exiled White Russian soldiers known as the “White Guards.”

After the war, Kovalevskii began laying down roots in Spain but hoped to return to Russia to redress his grievances with the “the common enemy – Communism” and restore Tsarist Russia to the political map of twentieth-century Eurasia. “The Whites saw themselves as the last pillars of imperial Russia,” the authors explain in their introduction, and “it was precisely they, exiles without passport or a penny to their name, who were, in their opinion, the real Russians.”

Following the outbreak of World War II and Nazi Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Kovalevskii and a number of his White Russian companions finally got the opportunity they had been waiting for. Although neither the Spanish or German military leaderships were interested in Russian volunteers, Franco’s dictatorship eventually gave way, enlisting dozens of White Guards and other Russian émigré volunteers for mobilization towards the Eastern Front. Yet to Kovalevskii’s and many other Russians’ chagrin, they were not allowed to officially join the Spanish Blue Division, the contingent of Spanish volunteers fighting for the Nazis.

Following a less-than-spectacular march through the streets of the Spanish city of Burgos, which had served as the base of operations for Franco’s military uprising during the civil war, the Spanish 250th Infantry Division set out for the Eastern Front by way of France, Germany, and Poland. Upon arriving in the eastern fringes of a now occupied Poland, Kovalevskii frequently observed what he believed to be the socio-cultural remnants of his “old Russia.” As the Blue Division crossed into the western stretches of the Soviet Union, Kovalevskii saw half-emptied villages and—in his view, happily—ideologically-indifferent populations.

In his mind, Kovalevskii was returning to his homeland as a patriotic liberator, not an anti-Bolshevik aggressor. “The sincere joy of liberation from the Bolshevik yoke,” he wishfully explained, “was visible on everyone’s face.” Kovalevskii found vestiges of Imperial Russia surviving in the shadows everywhere: “Pre-revolutionary Russia’s old family way of life had not suffered” under the twenty-four years of Bolshevik rule, and the “authority of the father and mother was still strong.” While “the Soviet regime was horrible,” he laconically concludes, Russians “had maintained [a] purity of soul.”

Kovalevskii makes a number of observations of both his Spanish and German co-combatants, including what he viewed as the former’s incurable backwardness (“every Spaniard is an embustero [rogue or cheat] by nature” and the latter’s tendency towards fanatical leader worship (the “deification of the Führer in Germany…was revolting to people”).

Kovalevskii also witnessed minor episodes in the Nazi-led genocide against the European Jewry. As the 250th Infantry Division briefly passed through the city of Grodno (in today’s Belarus), he observed a group of Jews “who were particularly noticeable now by the yellow, five-point stars on their right breast,” being forced by Wehrmacht soldiers to repair a heavily-damaged road: “It was pitiful to see,” he writes, “without forgetting even the crimes of their fellow tribesmen, the young girls, yesterday’s young ladies, puttering about in the dust and serving as a laughing stock for any passer-by.” Kovalevskii notes that Jews “were only allowed to live in defined quarters of the city—the ‘ghetto’, and where there were few of them—in concentration camps.” Neither “their rights nor their lives were protected by the law,” he explains, “and if they got in someone’s way, or as a means of repression, they could [be] ‘taken out.’”

In February 1942, Kovalevskii came down with an unidentified illness while fighting on the Eastern Front and was evacuated to a military hospital in Russia’s Novgorod oblast. The following day his military hospital was evacuated, due to westward-moving hostilities between the Wehrmacht and the Red Army and ended up being relocated to another military hospital near Cologne, Germany, where he remained until returning to San Sebastian, Spain a few months later. Although his post-WWII activities remain unclear, it appears Kovalevskii settled into some form of semi-retirement in Spain, which is where he began writing his memoirs as an unrepentant White Russian turned Nazi collaborator, most likely during the late-1940s and 1950s.

The revelation of Kovalevskii’s experiences as a volunteer Russian soldier affiliated with the Blue Division has been made possible only with Seixas’ and Beyda’s painstaking, international archival research. The unexpected discovery of an incomplete version of Kovalevskii’s memoirs at the Hoover Institution Library and Archives led them on a quest for the missing chapters in Russia and Spain. (Having pieced together the memoirs and scattered writings of Ruth Williams Ricci, another far-right war volunteer during the interwar decades, I can attest to how difficult this kind of piece-by-piece archival research is.)

Aside from a fascinating glimpse into the frontline conditions experienced by soldiers and civilians in Poland and Russia during the highpoint of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, this well researched and translated book will undoubtedly serve as a valuable resource for both scholars and students interested in probing the motivations and perspectives of Nazi Germany’s far-right collaborators before and during World War II.

Brian J. Griffith is an Assistant Professor of Modern European History at California State University, Fresno, where he specializes in the political and cultural history of modern Europe, including fascism. More at brianjgriffith.com.