Staging Death in Southern Spain: The 1936 Córdoba Miner Strike

As Patricia Schechter dug into her family’s history, she uncovered one of the untold stories of the Spanish labor movement: an Andalusian strike in early 1936 grounded in a rich legacy of disciplined pacifism and sturdy worker cooperatives.

After the July 1936 military uprising that unleashed the Spanish Civil War, hundreds of men from the mining town of Pueblonuevo del Terrible near Córdoba (Andalusia) joined the “Batallón del Terrible” to defend the Republic. They first left to reinforce Hinojosa del Duque to the north and, later, Pozoblanco, the headquarters of the Civil Guard to the east. In October, Pueblonuevo was overrun by rebel troops, but for the rest of the war the town and its many mines and metal shops were mostly quiet, as about two-thirds of the population melted back into the surrounding rural villages where they maintained family ties. Goading job advertisements in the press and leafletting by the Falange urging a return to work late in 1936 yielded little response. While some individuals from the area made their way into combat in the northern provinces, about fifteen men from Pueblonuevo and its neighboring village Peñarroya wound up at Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria—an ordeal which fewer than half survived.

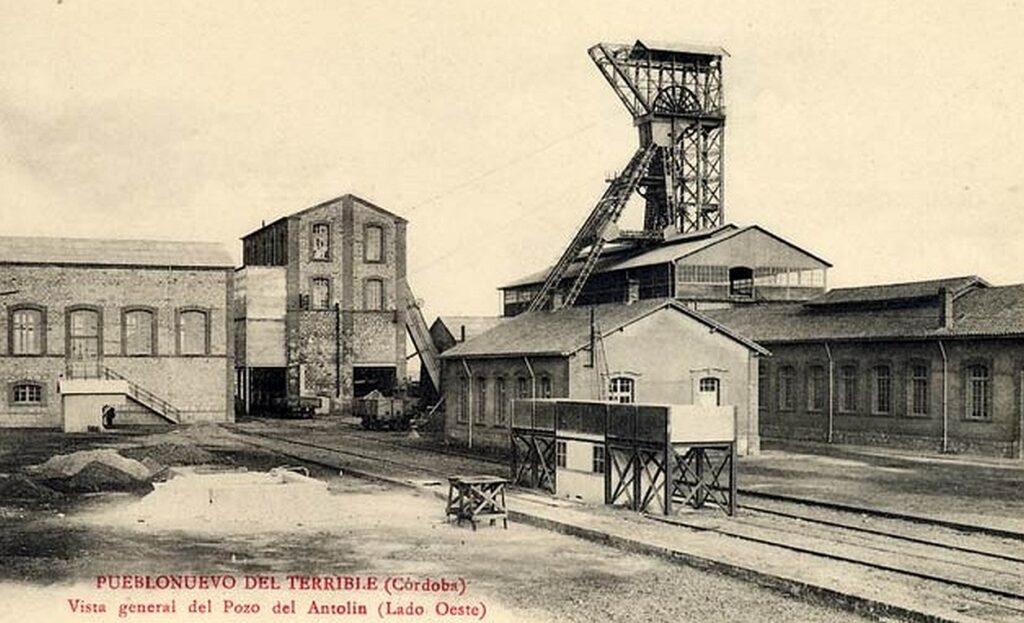

The young German photographer Gerda Taro came through the Córdoba front in September and took some pictures, including several of the Chapaiev Battalion of the XIII International Brigade stationed there. Still, the Córdoba province is mostly overlooked in general treatments of the war and its causes, even though it was the backdrop to some extraordinary labor activism in the run-up to the war, including a spectacular occupation and hostage-taking at the Antolín mine in May-June 1936. While the revolutionary actions of Asturian miners in the north grabbed headlines 1934-36, the quieter insurgency of miners of Pueblonuevo del Terrible has remained one of the untold stories of the Spanish labor movement. But what happened at Antolín points to a rich labor heritage of disciplined pacifism, sturdy worker cooperatives, and careful mentorship by organizers of the UGT, a labor union affiliated with the Socialist Party (PSOE).

I began my research into Pueblonuevo del Terrible on a quest for family history. My great grandfather, José Becerra Tapia, was a functionary of the ayuntamiento, the municipal government, from 1934 until his death in 1955. My grandmother, his eldest child, was born and raised in the village. My mother was baptized in the momentous year of 1936, and she has a faint memory of the last battle of the Córdoba front during the Civil War. It is one of her earliest childhood memories. She recalled being pushed to the ground, face forward, in a freshly furrowed field as the battle of Valsequillo broke out in early 1939. Valsequillo was one of those bloody, inconclusive engagements of the late war, largely forgotten with all eyes on Madrid and Barcelona.

My research into newly available sources suggests that the pacifism and nonviolence characteristic of striking miners in Córdoba was grounded in longstanding traditions of cooperation. The cooperative impulse had many sources, notably in worker self-help traditions stretching back to the early nineteenth century. When mining started north-west of Córdoba in the 1880s, mineworkers in Pueblonuevo del Terrible were paid decent wages. They were also paid in cash, rather than the scrip common in traditional company towns or the pittance of pesetas and meals doled out on the region’s latifundios. By the 1920s, working class residents had built a robust infrastructure for self-directed economic and political activity. Some 20,000 people from Pueblonuevo del Terrible, known as terriblenses, supported a cooperative for foodstuffs, a Casa del Pueblo for education and organizing, two newspapers (El Ideal and La Lucha Social), a federation of mining syndicates, and their crown jewel: the Casas Baratas Pablo Iglesias, 100 units of cooperative worker housing that were named after the founder of the Socialist Party and became the model for a national program during the Second Republic.

The terriblenses sought integration and participation in Spanish civic life. From their grassroots petition for municipio status in the 1880s to residents’ bid for the city via cooperative home ownership in the 1920s, their arguments were couched in patriotic love of country. In the 1910s, the UGT sent organizers to the area who lent support to syndicates and who themselves ran for office representing the PSOE, challenging the domination of conservatives at the polls—even if only symbolically. Francisco Largo Caballero, the Socialist leader who would serve as Prime Minister during the war, ran for office in the olive growing region of La Campiña, south Córdoba, in 1919. Ramón González Peña, a miner’s son from Asturias, also ran for election that year in the north of the province. Both men lost, in Peña’s case due to considerable corruption and threats of violence. Largo Caballero left the region, but Peña stayed and fostered the PSOE in the mining syndicates in north Córdoba and Ciudad-Real through most of the 1920s. The overall result in Pueblonuevo was a high-functioning worker public sphere. Peña’s organizing success on the ground provides context for the tendency among right-wing elements in the area to continue to play dirty. Checked by sheer numbers before the Primo de Rivera dictatorship (1923-1930), conservatives followed the fascist playbook after 1923. Authorities criminalized dissent, bad faith monarchists in elected office disabled the city council by boycotting meetings, and anonymous reporting and letter-writing campaigns slandered the worker population as communists, transients, Africans, and foreigners.

Still, despite the bad press, a pacifist and non-violent approach to conflict matured alongside workers’ social institutions in Pueblonuevo. In May of 1920, while in the United States members of the United Mine Workers and company “detectives” engaged in a lethal shoot-out in Matewan, West Virginia, killing seven, the miners of Terrible were in the middle of a successful 63-day strike during which not one life was lost holding the line. This outcome was truly extraordinary. Conflicts around the same time in Oviedo and Huelva, for example, involved bombings and outright assassinations. The terriblenses, by contrast, left town for the surrounding villages, staying far away from the police and the Civil Guard. The worker public sphere in Pueblonuevo mitigated violence between the Popular Front’s election in early 1936 and the military uprising in July. Especially in Madrid, this period witnessed disorderly and violent strikes in the spring and then murderous attacks against the church, fascists, and spies from the left in the summer. Yet insurgency looked very different in Córdoba. There, the miners of Pueblonuevo extended their pacifist tactics in a more measured—if desperate—response to economic conditions.

On May 28, 450 miners sequestered themselves inside the mine Antolín, the last of the great coal pits of the historic Terrible group. Disappearing into the earth, the miners performed a kind of funeral theatrics for 19 days, staging the “death” of the partnership of labor and capital by fusing their destiny with that of the mine itself. The telephone at the bottom of the pit permitted the strikers to speak from the metaphorical grave. The occupation turned Antolín into more than a would-be tomb; it was also a prison. At least four hostages were taken. The occupation was the fifth work stoppage at Antolín that year and it sparked an impressive set of sympathy strikes in the area. In the end, however, the strike could not leverage control over the miners’ economic destiny nor prevent the company from divesting from its operations in Córdoba province. The towering headframe of the modern mine Antolín threatened to become a headstone.

The strikers’ voices are almost impossible to hear in the extant record. Leadership likely took cues from the wildly successful and widely reported factory occupations in Paris earlier in the year, instigated by communist organizers. An equally dramatic and victorious factory occupation would occur in Flint, Michigan in December. The Paris and Michigan episodes made international headlines, unlike the Spanish case. French and U.S. workers played successfully on gender norms and scripts to garner public support. By engaging the media in their topsy-turvy inversion of work and home, strikers in the French and Flint cases appealed to public opinion by projecting a festive, carnival atmosphere. In Paris, the distress of the hostages was mitigated by the workers bringing in their families and children into the factory space, singing songs and playing games. In Flint, meal prep in a community kitchen turned women’s strike support into normative domesticity, visible as “camping” or “picnicking” at the General Motors plant.

At Antolín, however, Spanish women could not draw on well-grooved media scripts of domesticity to reframe their political activity as caretaking labor. The daily ritual of passing baskets of food and blankets down the mine shaft lacked the folksy spirit fostered by the community strike kitchen in Flint. Quite the opposite. In their efforts to hold the line, Spanish women were denigrated in the press as a vicious “lynch” mob who almost beat to death two young men who escaped the occupation. In contrast to the tidy domesticity among autoworkers at GM displayed in newsreels across the U.S., the miners at Antolín were read as gender deviants. The press negatively sexualized them as “sleeping on top of one another” to keep warm, their bodies filthy with human excrement due to the lack of facilities. By descending into the pit, miners at Antolín may have intended to stage a drama of self-sacrifice. But this drama was not readable in acceptably Spanish cultural terms. Instead, the occupation had a scrambling effect, dramatizing the unreadable, senseless conditions workers faced at this moment.

Left, right, and center, Spanish observers found the occupation of Antolín almost impossible to narrate, calling it an “anomaly,” “absurd,” “strange,” and “chaotic.” The fact that these insurgents struck against the contract recently signed by the miners’ Federation chilled reporting by the Madrid newspaper El Socialista, whose editors all but ignored them. Commentators in Córdoba judged the occupation negatively for its “revolutionary flavor,” but neither worker ownership of the installations nor nationalization of the mines was on the list of demands. They mainly protested forced layoffs. Based on their place-based knowledge, workers knew that the mines were full of coal. (In fact, Antolín still turned a profit when it finally closed in the 1970s.) The terriblenses also knew that Córdoba province needed coal to fuel its trains and to stoke the local thermoelectric plant. Moreover, closing mines deprived residents of access to fuel and water, both of which were completely controlled by the mining company. Firings, layoffs, and mine closures thus threatened residents’ survival on many levels. In the end, the strike secured negligible contractual gains while those charged with hostage taking faced prosecution.

And my great grandfather José, the municipal public servant? At city hall, he signed off on the seizure of the Casas Baratas by the invading forces in March 1939. A few months later, he approved outlawing the housing cooperative, the Cooperativa Pablo Iglesias, under Franco’s “Law of Political Responsibilities.” These actions point to a critical element in the fascist playbook: stealing from the poor. There is much more to say about the dynamic working-class town of Pueblonuevo del Terrible. About my great grandfather José, I can only say that it could have been much worse.

Patricia Schechter has taught at Portland State University in Oregon since 1995. Her book, El Terrible: Life and Labor in Pueblonuevo, 1887-1939, from which this article is drawn, will be out with Routledge this summer. More at www.pdx.edu/profile/patricia-schechter.