“Recovering the Black Antifascist Tradition Means Recovering the Best Features of the Left in US History.” —Jeanelle Hope and Bill Mullen

The roots of fascism lay right here in the United States. In fact, anti-Blackness is a persistent feature of fascism in all its forms. But there is a long lineage of Black antifascists that still have things to teach us.

When the House Un-American Activities Committee was first created, in May 1938, its chair, Texas Democrat Martin Dies, identified communism and fascism as dangerous foreign threats: “un-American doctrines” that, he said, “can only be fought with true Americanism.” Indeed, the terrifying prospect that fascism might “come to America,” which has been regularly invoked from the 1920s to the present, implies a soothing, even flattering, premise—namely, that it is not from America to begin with.

It’s a comforting notion, to be sure, but also one that recent scholarship has shown to be untenable. Last fall, the book Fascism in America, edited by Gavriel Rosenfeld and Janet Ward, pointed to the tremendous strength and persistence of fascist currents in American history. This spring, Jeanelle Hope and Bill Mullen add fuel to the fire with their book The Black Antifascist Tradition: Fighting Back from Anti-Lynching to Abolition (Haymarket).

Hope and Mullen present three central arguments. First, they contend that the roots of fascism go back farther than Hitler and Mussolini, to both European colonialism and racial oppression in the United States. It’s no coincidence that the Nazi race laws were inspired by Jim Crow. Second, they argue that anti-Blackness is both a founding principle and a persistent feature of fascism in all its forms: “there is no fascism anywhere,” they write, “that is not also anti-Black.” Finally, they show that many of the earliest and most effective attempts to identify and fight fascism have been made by scores of radical thinkers, activists, and organizations—from Ida B. Wells and Cedric Robinson to Angela Davis, the Civil Rights Congress, the Black Panther Party and Black Lives Matter—who together make up something that we could call a Black anti-fascist tradition. It’s a tradition that’s been partly forgotten and is often misread, but that, Mullen and Hope are convinced, can serve as a powerful inspiration to progressive activists today.

Jeanelle K. Hope, a scholar-activist from Oakland, California, teaches African American Studies at Prairie View A&M University. Bill V. Mullen, Professor Emeritus of American Studies at Purdue, is co-founder of the Campus Antifascist Network. I spoke to them in early April.

Who did you write this book for?

Jeanelle K. Hope (JKH): As a scholarly intervention, this is our response to a host of new studies in fascism and antifascism, in which we try to center the debate on the Black antifascist experience and the centrality of anti-Blackness in all forms of fascism. But we are also writing for organizers and activists working today who are looking for tactics and strategies. Haymarket Books has been a great partner in our effort to reach those folks.

Bill V. Mullen (BVM): We are also hoping to reach students across the country, which is why we included a sample syllabus in the book. Some colleagues have already told us they plan to use it in their classes, which is really gratifying.

Many recent state laws explicitly prohibit teachers from suggesting that US history is intimately connected with racist ideologies and practices. You go a step further, arguing that the very origins of fascism can be found on this side of the Atlantic. How do you feel about the fact that your book will likely be illegal to teach in certain states?

JKH: (Laughs.) We haven’t yet been notified that we are on any banned-book list! If we were, it’d be a badge of honor. Kidding aside, we knew what we were doing. I mean, the Black antifascist tradition that we outline includes an entire canon or writers and thinkers whose works have already been banned multiple times. From our point of view, which fortunately is shared by many, there is something fundamentally valuable about reading banned books.

BVM: In our epilogue, we explicitly address the recent legislative war on free speech and academic freedom in this country. But, as Jeanelle said, many of the folks we write about were imprisoned, persecuted, or blacklisted for their ideas and activism, from W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson to Claudia Jones and Assata Shakur. Some of the great heroes in the Black antifascist tradition have been real targets of suppression and censorship. In a sense it’s ironic that, as many of us are trying to recover their voices, we’re facing censorship once again. If anything, it shows that their ideas continue to be a threat to the state and mainstream bourgeois society.

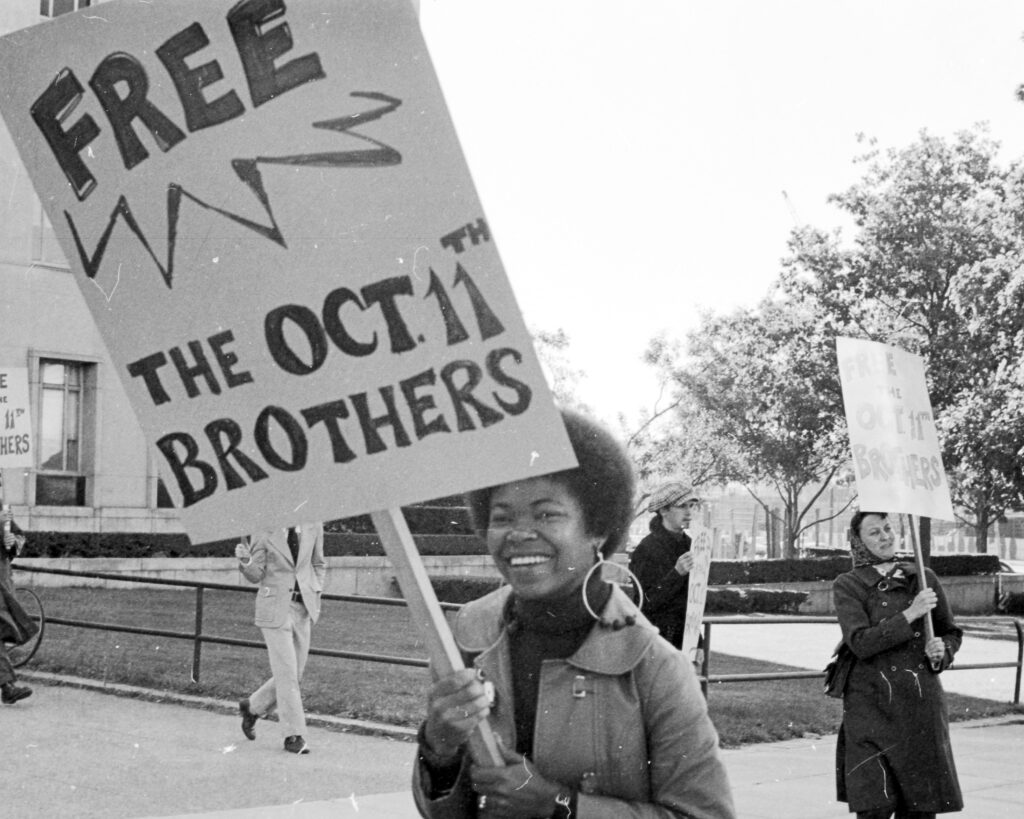

Demonstrators in DC on Feb. 7, 1974, the first day of the trial of the prisoners who rose up on Oct. 11, 1972. Photo Washington Area Spark. CC BY-NC 2.0

What is it about the current moment that makes a book like this both urgent and possible? On the one hand, you draw on work that’s been going on since the late 1980s and early 1990s—I’m thinking of Robin D.G. Kelley, for example. But on the other, there seems to be more space now to recover U.S. radicals associated with the Communist Party, the anarchist movement, and forms of armed struggle against the state. Are the Cold War taboos that persisted into the beginning of our century finally melting away?

BVM: That’s an interesting question. Our book is clearly a post-2016 intervention: Trump scared everyone into thinking that fascism might be on the rise in this country. Both Jeanelle and I have backgrounds as antifascist organizers. Since 2016, as a cofounder of the Campus Antifascist Network, I’ve been collecting resources, both online and through projects like The US Antifascism Reader that I put together with Chris Vials. But you’re right that Robin Kelley’s work has been very important. He helped us look with fresh eyes at the role of the Communist Party, without which the history of American antifascism, and Black antifascism, cannot be written. His Hammer and Hoe, on Alabama Communists during the Great Depression, came out in 1990 and inspired my first book, which centered on Black cultural politics in Chicago between 1935 and 1946, the era of the Popular Front against fascism. Part of that book was about the Double Victory Campaign, which was initiated by the Black press and the Chicago Defender, and which sought to defeat fascism abroad and at home. Jeanelle and I return to that moment in our book, in which we identify it as the first mass Black antifascist movement.

JKH: I first started thinking about American fascism and Black antifascism in graduate school, around 2010, when I started researching Afro-Asian solidarity in the San Francisco Bay Area during the 1960s and ‘70s, involving the Black Panther Party, Asian-American groups, and other non-Black radicals. One thing that kept coming up was the 1969 conference on the United Front Against Fascism. At the time, I didn’t quite know what to do with that, but Bill and Chris’s Antifascism Reader helped me piece things together and see how the front against fascism served as a tool of solidarity building. In terms of our current book, 2016 was a key moment, but so was 2020, when Black Lives Matter rose in protest over the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others. What’s also been crucial in more scholarly terms is the work on Afropessimism done by folks like Frank B. Wilderson, Saidiya Hartman, and Jared Sexton, which has given us language to talk about the centrality of anti-Blackness in the national and global history of fascism.

Your book doesn’t just rescue the archive but re-signifies it through the concept of the Black antifascist tradition. For example, you take the label of “premature antifascism” that the US veterans of the Spanish Civil War adopted as a badge of honor, and apply it to Ida B. Wells, the turn-of-the-century anti-lynch activist, who you identify as a “premature Black Antifascist.”

BVM: In our book, we argue that fascism always includes anti-Blackness. For us, the key point, even going back to people like CLR James and George Padmore, was to identify blackness as a central element in the discursive analysis of fascism. We felt that was an important task that had not been accomplished in any significant way. For Frank Wilderson, one of those places is South Africa, where Apartheid is founded on anti-Blackness, and from where it travels into the political discourse of the United States. But as we dug into the archive of anti-Black writing, we also located the roots of Black anti-fascist thinking and writing.

The twentieth-century history of antifascism is marked by alliances—the United or Popular Front—but also by divisions among Communists, Socialists, Anarchists, and Liberals, which often manifested in disagreements about tactics and strategy. In your book, you show that this was true for the Black antifascist tradition as well—for instance, when the Black Liberation Army, which was founded in 1970, denounced any kind of “reformism” as a fascist complicity. But what you don’t do, it seems to me, is take a position in these disputes. You don’t really assess the effectiveness of the tactics proposed over the years. It’s not clear to the reader, for example, whether you think that armed struggle was a viable tactic then or could be one today.

The twentieth-century history of antifascism is marked by alliances—the United or Popular Front—but also by divisions among Communists, Socialists, Anarchists, and Liberals, which often manifested in disagreements about tactics and strategy. In your book, you show that this was true for the Black antifascist tradition as well—for instance, when the Black Liberation Army, which was founded in 1970, denounced any kind of “reformism” as a fascist complicity. But what you don’t do, it seems to me, is take a position in these disputes. You don’t really assess the effectiveness of the tactics proposed over the years. It’s not clear to the reader, for example, whether you think that armed struggle was a viable tactic then or could be one today.

JKH: That’s a fair point. We don’t take a stance on the effectiveness of tactics. What we tried to do instead is lay out the whole multitude of tactics used, and to underscore the importance of fighting fascism as a united front, but on multiple fronts. Ida B. Wells urged folks to leverage the press, pick up their gun, pick up their stuff and leave. We look at ways that people like William Patterson fought fascism through the courts. We look at the mobilization of the cultural front, including poetry and comic books. We talk about the Black Panthers, about autonomous zones and mutual aid and the struggle waged by political prisoners in this country, all the way to the hijackings of the Black Liberation Army. Although we don’t assess which tactics proved more effective, it’s clear to us that some, including the more violent ones, may have been more alienating than others. But for me the key is that there are, and should be, various ways to fight fascism. After all, the Right organizes in many ways as well, from Moms for Liberty to the Proud Boys.

BVM: Rather than taking sides, our goal was to lay out the terms of the debates. When George Jackson was in prison, he corresponded with Angela Davis, debating definitions of fascism. Jackson thought that even capitalist reformism was a form of fascism, meaning that fascism was already here. Davis disagreed, arguing that the United States was in a state of incipient fascism. Looking back on it, I think both were right in some sense. Jackson and the Panthers were part of what we call first-wave abolitionism. The prison movements at Folsom and San Quentin and Attica that led to massive uprisings were a product of one particular interpretation of fascism coming down, partly, from George Jackson. Well, it turns out that we needed those prison rebellions. Whatever their immediate outcome, they were a necessary step forward politically to lift what, at the time, was a massive specter of racist oppression. Then Davis carries her work forward and becomes a major theorist of prison abolition, arguing, as she has to this day, that the prison industrial complex, if it’s not checked, will lead us down a dark path to full-blown fascism. Our role as authors of this book, I feel, is not to take sides in these debates, but to teach them and talk about them.

JKH: Similarly, the 1970s debate between the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army over the usefulness of electoral politics is useful for us today, as the Democratic Party is trying to convince us that the only way to save the country from fascism is to vote for Joe Biden. Well, that cannot be the only tactic.

Since you brought us back to the present, Jeanelle, can you share some of the most interesting or effective antifascist projects you know of in the US today?

JKH: I appreciate the opportunity to spotlight work that may not be immediately identified as antifascist. I’m really inspired and heartened by the folks working around Stop Cop City in Atlanta, who are trying to fight the creation of a testing ground for new police tactics and weaponry in the heart of the city. I’m also deeply impressed with everyone doing mutual aid work— programs that were first pioneered by the Black Panther Party—providing anything from food to bail, including here in Fort Worth, where Funky Town Fridge has been placing refrigerators that become centralized spaces for food donations across historically Black and Brown communities. And of course, the multiple ways in which people have been calling for the United States to stop funding the ongoing war and genocide in Gaza.

BVM: In our last chapter, which is called Abolitionist Anti-Fascism, we discuss some hidden but important antifascist moments in the Black Lives Matter movement. The Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, for example, or We Charge Genocide, which emerged in Chicago after the Trayvon Martin shooting and denounced the torture of Black youth by the Chicago police. The group took its name from the 1951 petition by the Civil Right Congress, which, as we explain in the book, used the 1948 United Nations Genocide Convention to denounce the treatment of Blacks in the United States. These Chicago youth, too, went to the United Nations.

You said some of these projects would not be immediately identified as antifascist. Which brings me to my final question: both “fascism” and “antifascism” have long been loaded terms here in the United States—perhaps to such an extent that they divide more than they unite. The widespread demonization of “Antifa” has not helped, either. Yet you invoke both terms prominently and unapologetically.

BVM: We do, because we are trying to recover “antifascism” as a term and mainstream it, to put it on everyone’s political agenda. It’s been controversial since the Cold War, when some of the Black folks who fought fascism in Spain were forced to testify in Washington and asked to denounce their own antifascism—which they refused to do. In this country, in other words, the state itself waged an attack on antifascism because of its association with the Communist Party. To recover the antifascist tradition means to recover many of the best features of the Left in US history. The other thing to keep in mind is that our term “anti-Black fascism” is theoretically important. We want people to use it as a lever for their own activism. We feel like the conversation and the political fightback is not complete without some understanding of both anti-blackness as an element of fascism and the wonderful, robust tradition of Black antifascism.

Sebastiaan Faber teaches at Oberlin and is a member of the ALBA Board.