Courier for the Republic: The Short, Adventurous Life of Charles Jacobs

What Was a Young Dutch Pilot Doing in Civil-War Spain?

Saturday, March 20, 1937. Farmers at work in a vineyard near Narbonne, in southern France, see a Dutch plane circling for hours. At four in the afternoon, a car arrives whose driver unfolds a white sheet. At this signal, the plane lands on a bumpy field. Gendarmes, alerted by locals, show up and arrest the pilot. The car drives away at a breakneck speed. The pilot claims his name is Schumacher. He works for International Red Aid, he says, and he was on his way from Toulouse to Marseilles on an assignment. A few days later, however, the pilot vanishes, and the plane is set on fire. The incident makes it into the Dutch papers. The owner of the single-engine Fokker plane, they report, was Charles Erik Jacobs from Amsterdam.

Although Charles Jacobs was only 21 at the time, he was a licensed pilot and the owner of no fewer than three aircraft that he used to maintain a courier service to Barcelona, regularly delivering relief supplies to the Spanish Republic and the International Brigades. These almost certainly included weapons, perhaps even complete fighter planes. In fact, Jacobs worked as an agent for International Red Aid, the medical and humanitarian affiliate of the Communist International. The individual who financed these missions was a Russian oligarch, Michael Holzmann, who lived a stone’s throw from Jacobs in Amsterdam. Known as a swindler and black-marketeer, Holzmann was closely watched by the Dutch authorities—which is why there is a wealth of information about Communist-inspired international support for Spain in the Amsterdam police archives.

Michael Holzmann, born 1891 in Kharkov, had become very wealthy by doing business in Western Europe during World War I. Since those businesses could not always bear the light of day, he had been expelled as persona non grata from Germany (1926), France (1929), Italy (1931), and Austria (1932). He was known as a “dangerous international extortionist,” addicted to gambling and connected with a spate of suspicious individuals from around the world. When the Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936, he happened to be in Madrid. As commissioner of the Koolhoven Aircraft Factory in Rotterdam, he sold fighter planes to the Spanish government. Through his good contacts with the Dutch embassy, he managed to obtain a passport for stateless people that he used to move to Amsterdam with his wife Anastasia, his son Boris—who was also stateless and had been expelled from France as a communist in 1936—and six very expensive borzoi dogs.

From Amsterdam, Holzmann continued his lucrative business dealings. He delivered dozens of planes, an “ambulance train,” blankets and medical supplies, supposedly to France, but actually to Spain. Since the Netherlands had signed a Franco-English non-intervention treaty at the beginning of the Civil War, this business was illegal; and because Holzmann could not sign business transactions as a stateless person in the Netherlands, he was forced to use intermediaries. This was no problem for him, as he had relationships up to the highest diplomatic and government circles—including the Dutch immigration police.

On May 6, 1937, he had lunch with Bernhard zur Lippe-Biesterfeld, the German nobleman who had married the Dutch crown princess four months earlier. Holzmann, according to the many dozens of pages of his Dutch Central Intelligence file, was an anti-fascist who acted on behalf of International Red Aid—that is, the Comintern. According to others, he also sold material to the Francoists. Either way, the Dutch authorities saw this as a violation of the non-intervention treaty. During his stay in Amsterdam alone, Holzmann was charged with crimes ranging from aiding Spain to rape, blackmail, swindling and sex orgies. Yet the file also includes many favorable references from prominent Dutch citizens. The complaints against Holzmann sometimes have decidedly anti-Semitic overtones, something that the National Socialist press in several European countries would later be quick to pick up on. In 1939, when Holzmann was finally expelled from the Netherlands for “disturbance of the public order,” the news was covered by papers in several countries. He left for London and eventually settled in Argentina.

Charles Jacobs was one of Holzmann’s closest collaborators; a roommate later stated to the police that they talked on the phone daily. Jacobs’ life story has spurred at least as much speculation as that of his boss—including a claim that he was murdered. Again, however, the Dutch police archives offer some insight.

Charles Jacobs was born in 1916 into a well-to-do progressive family. Trained as an electrical engineer, he had earned his pilot’s license in 1935 and became a commercial pilot from Schiphol Airport. By the age of 20, he already owned his own plane and a luxury car, a convertible. In mid-October 1936, Jacobs and his plane made the papers: he was to fly it to Africa to film wildlife for a French film company. A darkroom would be set up in the plane. It turns out the whole expedition was a cover-up. In fact, Jacobs had already begun his “scheduled service” to Spain, and he never got further south than Barcelona.

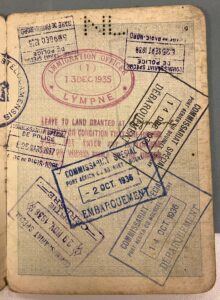

This is evident from his passport, which, along with a photo album and some other items, has been preserved in the archives of his younger sister Anna Jacobs (1921-2009). According to the staggering number of stamps in this passport, Jacobs began his flights from Paris (Le Bourget) via Toulouse to Barcelona on October 2, 1936. He would stay in Spain for at least one, but usually a few days, flying back and forth at least two or three times a month. Paris was home to the Western European office of the International Red Aid and housed representatives of the legitimate Spanish government, who were in charge of international arms procurement.

Jacobs’ primary contact in Barcelona was Jeanne Schrijver, a seasoned Communist who worked for the Dutch Communist Party (CPN), the International Brigades and Radio Barcelona. It was Schrijver who told him what he should say and do on his expeditions. (Later, she’d become the first woman to join the armed resistance in the Netherlands during the German occupation; she committed suicide shortly after her arrest by Germans in December 1942.) Not much is known of Schrijver’s work in Spain beyond the fact that she crossed the Spanish-French border numerous times for a number of unexplained missions. Possibly Jacobs acted as her pilot on these missions as well. One thing we do know is that there was frequent illegal air traffic between southern France and Spain. It was later revealed, for example, that in the September-October 1936 period alone, more than 150 Russian aviators were flown across the French-Spanish border to serve in the Republican army.

As far as we know, Jacobs was not involved in this operation. He did, however, smuggle gold and other valuables out of Spain to buy weapons. His passport contains his registration with the Generalitat de Catalunya, Seguretat Interior (Internal Security Service), dated Nov. 30, 1936. It also contains a scrap of paper with the letterhead Ministerio de Marine y Aire, Subsecr. On May 23, 1937, there is a notation written in Catalan in his passport that he carried 900 (illegible) and 130 (illegible) extra. It may be that Jacobs transported aircraft purchased by Holzmann or lent his name and signature when purchasing and reselling equipment. One thing is certain: both Jacobs and Holzmann operated in a shadowy world where they handled massive amounts of cash.

A piece of that world was later mapped out by the famous Soviet spy Walter Krivitsky, who in August 1936, just a month after the outbreak of the Civil War, received a visit from a man at his home in The Hague. The man gave him an order: “mobilize all available agents and auxiliary offices to immediately set up a system to buy arms for and transport them to Spain.” Krivitsky immediately sent the Dutch Communist Han Pieck on his way. In Greece, through yet another intermediary agent, they managed to obtain 50 bombers and fighters for $20,000 each. Krivitsky, like Holzmann, set up import and export firms in a number of European cities to buy war equipment. It is not unlikely that the Krivitsky/Pieck and Holzmann/Jacobs teams were linked.

On May 23, 1937, Jacobs left Barcelona for the umpteenth time; on June 4, he was back in Amsterdam, where he had taken residence at the famous Schiller Hotel on Rembrandtplein, whose café-restaurant was known as a meeting point for intelligence officers of all nationalities, and where Jacobs would meet his Dutch Communist contacts. On June 10, Jacobs suddenly fell ill. Taken to the Wilhelmina Gasthuis hospital, he died two days later. Jeanne Schrijver returned to the Netherlands from Barcelona to attend his funeral.

Jacobs’s sister, Anna, believed that her brother was poisoned. Others claimed that he had committed suicide. The police chief agreed the case looked suspicious and ordered an investigation. Among the initial suspects was one of Holzmann’s connections. Yet the autopsy excluded any suspicion of murder or suicide. A very rare condition, acute spinal meningitis, had cut short Charles Jacobs’ brief but adventurous life.

Margreet Schrevel is a Dutch historian who worked for more than forty years as a researcher at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam. Translated by Sebastiaan Faber.