Premature Antifascism and The Power of Self-Identification

“Oh, you were a premature antifascist,” the chair of the Yale Classics department replied to Bernard Knox when, during a job interview in 1946, Knox told him about his stint with the International Brigades preceding his US army service during World War II. “I was taken aback,” Knox wrote later. “If you were not premature, what sort of antifascist were you supposed to be?” Other Lincoln vets who served in the US armed forces recalled the term being invoked as a marker of suspicion.

Although “premature antifascism” has been part of the American political lexicon for nearly a century, the origins of the term have long been shrouded in mystery and controversy. When the anticommunist historians Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes, writing in The New Criterion in 2002, declared it a “myth,” they did not bother to consider more interesting questions: Were Spanish Civil War veterans discriminated against during World War II? How did the meaning of the phrase evolve over time? And why does it continue to resonate today? Whether the phrase originated in an Army manual or was coined by journalists sympathetic to veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade is beside the point. The important thing is that it became a powerful form of analysis and self-identification for Spanish war veterans—and antifascists in general—to understand their politics and the subsequent discrimination they faced.

There is another reason why the history of the term matters. “Fascism” is a political term stripped of meaning. As Bruce Kuklick argues in Fascism Comes to America, everyone is a “fascist’ to their political opponents. Cold War liberals—and their neoconservative descendants—constantly invoked the specter of Munich to justify a militant foreign policy; few, if any, invoked the Spanish Civil War. Although by now it’s often used more generally to describe taking an unpopular political stand before it’s considered right to do so, “premature antifascism” has never lost its association with antifascism and the left. Far from being meaningless, “premature antifascism” is an invocation of political meaning—a marker of left-wing political identity.

To be sure, historians have not found a “smoking gun” document that conclusively proves that the Army engaged in systemic discrimination against Spanish Civil War veterans as a matter of policy. Officially, the War Department consistently denied that such practices existed. Still, given the general conservatism of the Army officer corps, its overall anticommunist orientation, and the sheer volume of reports of discrimination in postings and promotions by Spanish war veterans, that unofficial systemic discrimination was almost certainly happening. More importantly, Spanish Civil War veterans understood themselves to be victims of systemic discrimination in the US Army.

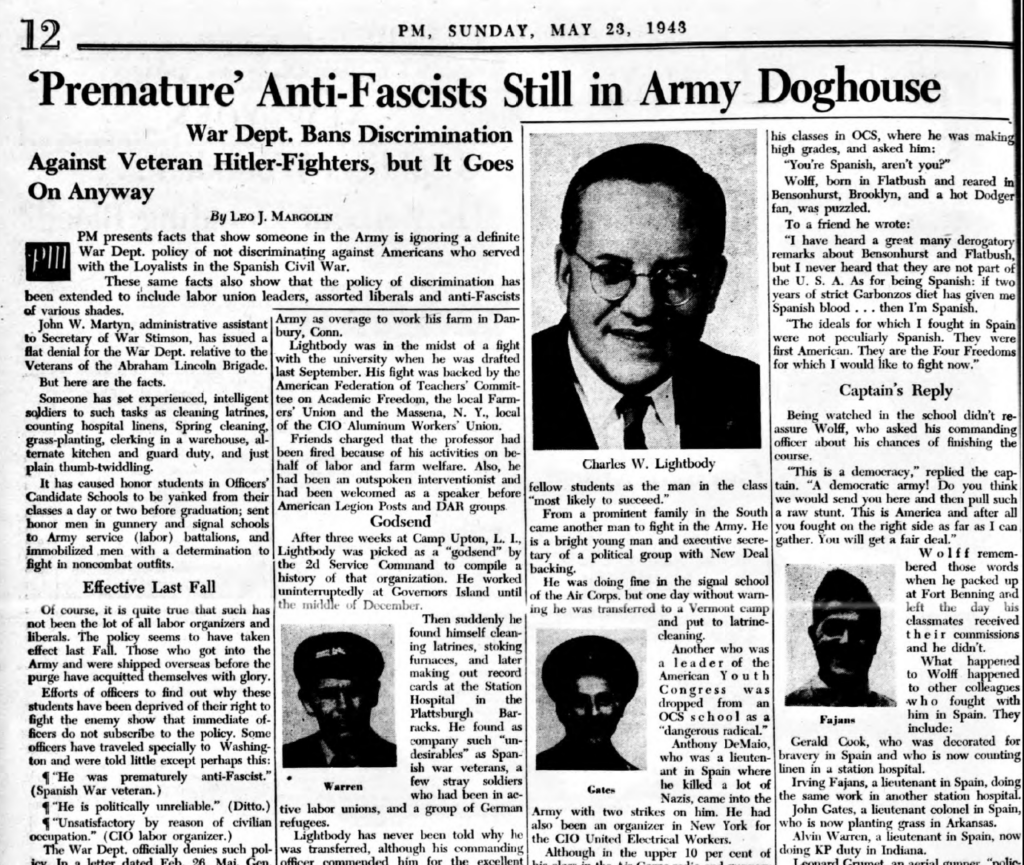

As Peter N. Carroll noted in the pages of The Volunteer back in 2003 and later in his book From Guernica to Human Rights (2015), the first time the term “premature antifascist” appeared in print was probably May 1943, when the New York tabloid newspaper PM used it to describe the discrimination Spanish war veterans faced. At the beginning of the year, Jack Bjoze, the executive secretary of VALB, had written a letter to President Roosevelt protesting the Army’s discrimination against Spanish Civil War veterans, particularly considering their “military experience in actual combat.” Since both the White House and the Pentagon failed to respond, in the spring Bjoze embarked on a lobbying tour of Washington, D.C. In April, Drew Pearson, the influential author of the syndicated column “Washington Merry-Go-Round,” published two stories about discrimination against Spanish Civil War veterans by the Army. The War Department issued denials, but stories of ill-treatment persisted. On May 23, 1943, PM dedicated a full page to the story under the headline “‘Premature’ Anti-Fascists Still in Army Doghouse,” specifically citing the washing out of qualified Spanish war veterans from Officer Candidate School. According to Leo J. Margolin, the author of the story, a group of concerned OCS commanders traveled to Washington in the fall of 1942 to determine why these candidates, who were well-regarded by both their commanding officers and their colleagues, were being denied commissions. “[They] were told little except perhaps this: ‘He was prematurely anti-Fascist.’ (Spanish War veteran).”

By the summer of 1943 the term had become the subject of political humor. Red Kann, a progressive voice in the Hollywood trade newspaper The Motion Picture Herald, included in his July 25 column an anecdote about an “actor, interested in liberal causes on his own time,” who was denied permission to shoot a picture on a military base. The alleged reason was that the actor had been labeled a “Premature anti-Fascist” on an Army dossier. Since Kann did not give any other information, the story is probably apocryphal. But it was the first allegation, in print, that the Army used the term “premature antifascist” in its official documents—an important, though possibly incorrect, part of the narrative. Ironically, at no point does Kann claim that the actor was a Communist, socialist, or Spanish Civil War veteran. He was simply “interested in liberal causes.” Three months after the first public use of the phrase, in other words, “premature antifascism” had already expanded its meaning to include broader discrimination against liberals and leftists.

In those first years, premature antifascism was used as a form of identification, as satire, and—importantly—critique. Liberal syndicated columnist Samuel Grafton wrote in March 1944 that “everyone has heard the many FBI investigator jokes, about the intense fear on the part of several of our government bureaus lest they make a slip and hire someone who was too hot an anti-fascist, too soon, a ‘premature anti-fascist.” Grafton’s column was not about the U.S. government’s discrimination about Spanish war veterans, Communists, socialists, or liberals—it was a scathing critique of U.S. policy towards France. The column was typical in its use of “premature antifascism” towards the end of the war. The phrase could refer specifically to veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, but it was also used by liberals, trade unionists, and Communists to refer to antifascism in general as a political orientation in the 1930s. In March 1946, Washington state Democratic congressman Hugh DeLacy gave a speech in New York City in which he related the story of a professor, a veteran of the Spanish Civil War, who “can’t get a job simply because Martin Dies [the chairman of the House Un-American Activities Committee] said that if you were against Hitler and Mussolini before December 7, 1941, you were a premature anti-Fascist.” The broader political sentiment mattered more than service in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.

The Communist Party USA—an organization that zealously guarded its terminology—used “premature antifascist” broadly in its own literature, to the point that in December 1945 a Party member complained in a letter to The Daily Worker of its overuse. Morris U. Schappes, a Party member and the editor of the magazine Jewish Currents, was convicted of perjury for refusing to name names of Communist faculty in the City College of New York in 1941; in 1944 the Daily Worker called Schappes a “valiant but ‘premature’ anti-fascist.”

Other Communist uses of the term invoked a broader struggle against racism and anti-Semitism. In July 1945, the CP-dominated New York City Teachers Union demanded an investigation into discrimination by the Board of Examiners, which controlled teachers’ licensing in New York, against teachers who had a record of “improving inter-cultural relations by combating anti-Semitism or anti-Negro prejudice, or to what might be cynically termed ‘premature anti-fascism.’” The union did not link the term to combat service in Spain, but directly tied it to anti-racist organizing in the United States. The union had a long history of this kind of work. The Teachers Union newsletter repeatedly condemned Jim Crow in the South and racial segregation in the North, rhetorically tying anti-Black white New Yorkers to Nazism and fascism. In fact, under the aegis of supporting the war effort, the union supported teachers who actively incorporated anti-racism and anti-fascism into their pedagogy. These commitments only intensified after the war. A report issued by the union in 1950 documented the widespread use of racist textbooks in New York City schools, often written by senior members of the Board of Education and the Board of Examiners. Critics of the Teachers Union have long lambasted the organization as simply a Communist front, but the union’s commitment to anti-racism as a political plank was not simply a cynical party dictate. For the Teachers Union, premature antifascism was indelibly linked to the broader struggle against racism in America.

By the end of the war, “premature antifascism” had two distinct meanings on the left. One was relatively narrow, based on the idea that the term was systemically deployed in the federal government and the Army to deny employment and/or commissions to radicals—particularly Communists and, in the case of the Army, Spanish Civil War veterans. The novelist Howard Fast used this narrower sense of the term in a telegram to President Harry Truman at the end of 1945 protesting the sacking of alleged Communist Robert Carse from the New York Port of Embarkation under pressure from Army intelligence. But the term was also used to denounce anti-radical discrimination more broadly. When, in 1948, Clifford Odets explained why he left New York City for Hollywood, he said: “I was looking for a period of ‘creative repose’: money, rest and simple clarity. A charge of ‘premature anti-fascism’ made it utterly impossible for me to serve the war effort.” Odets was not a Spanish Civil War veteran and, although he had briefly been a Communist Party member had not been formally active in the Party for over a decade.

By the mid-1950s “premature antifascism” had ceased to be a dynamic political phrase. It remained crucial to how the veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and members of the Communist Party USA understood themselves and their history, but it largely dropped out of the political lexicon of the day. But while the phrase seldom appeared in print in the 1950s except as a legitimation of the Communist Party’s antifascism, by the 1960s it reemerged as a metaphor for taking principled, unpopular political stands, only to be vindicated by history later. This was not limited to the left; in fact, some of its earliest users were conservatives. Vermont Royster, the editor of the Wall Street Journal, compared the experience being called a “premature anti-fascist” in the 1930s to the position of being a skeptic of American interventionism in Vietnam in a 1965 column— “if perchance you have never been enchanted by the limitless power of your country to support the world with dollars, or police it with soldiers, expect no accolades for prescience.”

Still, “premature antifascism” largely remained a marker of the left, associated through the 1980s with the Spanish Civil War and Lincoln veterans, while the 1990s saw the term become common enough to merit the investigation and debunking as an official term by Haynes and Klehr. The 1990s revival appears to stem from three distinct but intertwined factors: the gradual disappearance of Spanish Civil War veterans and radical activists from the 1930s; the “Greatest Generation” nostalgia industry that developed celebrating aging American veterans of World War II and its sanctification as “the Good War”; and finally attempts by the American left to contest the historical memory of the Communist Party USA around the end of the Cold War.

The phrase itself has continued to have political resonance in the twenty-first century. Contemporary use of “premature antifascism” generally mirrors that of Vermont Royster’s—invoking a principled, unpopular stand that eventually becomes vindicated and part of political common wisdom. John MacArthur, a supporter of Ralph Nader in 2000, invoked the term in a February 2004 column to vindicate Nader’s opposition to NAFTA and the Iraq War, noting that in the ongoing Democratic primary Howard Dean “presents himself as [an] anti-war, anti-corporate tribune.” MacArthur’s invocation as a form of praise and prescience became commonplace among leftists over the subsequent two decades. An alternative Jewish weekly invoked premature antifascism to justify its opposition to Israeli policy in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in June 2005. The phrase became a way to invoke an iconoclastic, rebellious, and left-wing history, and remained a defiant refrain even in the obituaries of Spanish war veterans. A column by John Nichols in the Wisconsin State Journal commemorating the death of Lincoln vet Clarence Kailin at the age of 95 in October 2009 marked his life as “Premature Antifascist—And Proudly So,” and noted that his final birthday party—fittingly at Kailin’s synagogue—included “political speeches calling for an end to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, for single-payer health care and for a reordering of the U.S. economy that would tip the balance away from Wall Street and toward Main Street.”

Kailin himself held a remarkably prescient understanding of American politics until the very end of his life. “Quick-witted and passionate to the last, Kailin laughed… at the notion that a centrist Democrat from Chicago named Barack Obama was somehow turning the United States hard to the left” and that such a transformation would have to come through grassroots organizing. Even at the end of their lives, premature antifascists continued to be unafraid of staking out unpopular political positions that ultimately proved not only correct, but within a decade became common wisdom.

David Austin Walsh is a postdoctoral associate at the Yale Program for the Study of Antisemitism. His book Taking America Back: The Conservative Movement and the Far Right, will be out in 2024.