How Contemporary Spanish Photo Books Redefine the Memory of the War

Contemporary Spanish photographers are finding new ways to return to the memory of the Civil War, departing from the sober documentary approach that was dominant until recently.

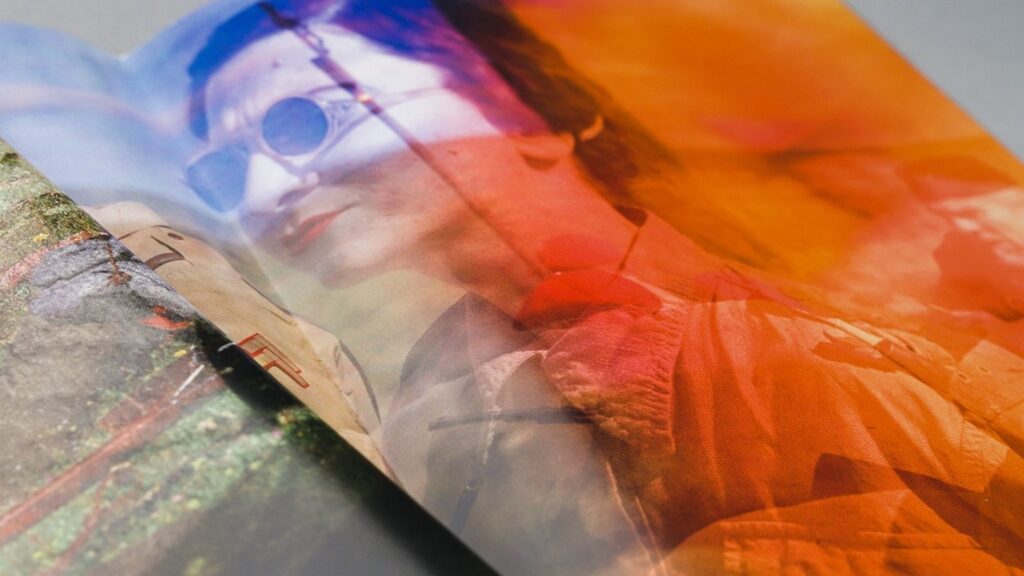

Julián Barón’s haunting photobook El laberinto mágico (The Magical Labyrinth, 2019), which you can leaf through here, features superimposed color photographs of soldiers and militiamen in battle wearing historical uniforms and carrying Spanish and Republican flags. The images seem to take us to a place we have never been—and yet it feels familiar. Although Barón’s photographs immediately make us think of the Civil War, their vibrant colors are surprising, even suspicious. And if we look carefully, we also discover objects from our present—a fire extinguisher, a microphone, a baseball cap—in the trenches among the militiamen. More surprising still are the spectators who seem to enjoy the show, raising their cell phones to record the scenes. In fact, what Julián Barón’s camera documents are re-enactments of mythical Spanish Civil War battles, which for several years now have been held on the very locations where those battles took place. Still, the photographs act like a trompe l’oeil: They generate time tunnels that connect past and present and force us to think about the present from the wounds that the war—now turned into a spectacle—have left in our society, while at the same time inviting us to reflect on the workings of collective memory.

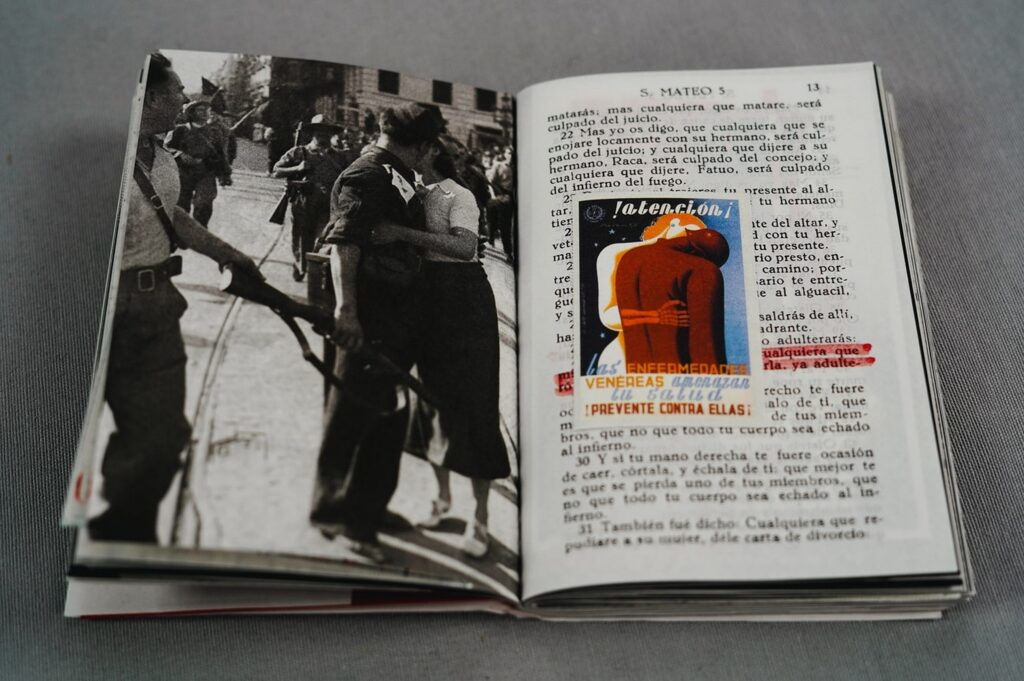

Barón is one among several contemporary Spanish photographers who are seeking to recover the past to engage in conversations about the present. The same year that El laberinto mágico came out, 2019, saw the publication of Flowers for Franco by Toni Amengual, which questions the survival of El Valle de los Caídos, where Franco was buried; War Edition by Roberto Aguirrezabala, which links the great wars of the 20th century—including Spain’ civil war—through stagings and documents; and Cristos y anticristos (Christs and Antichrists) by Javier Viver, who inserts photographs and propaganda posters from the Spanish war into a 1932 edition of the Gospel according to Matthew. In 2020, David García published El paseo, featuring photographs of locations holding mass graves from the war, while Hombrecino, by Susana Cabañero, tells the story of the photographer’s grandfather alongside her own story as granddaughter who wants to know what happened. These are just a few examples among many. Despite being very different, what these projects have in common is a desire to move beyond the strict documentary approaches that predominated in memory photography of the preceding twenty years.

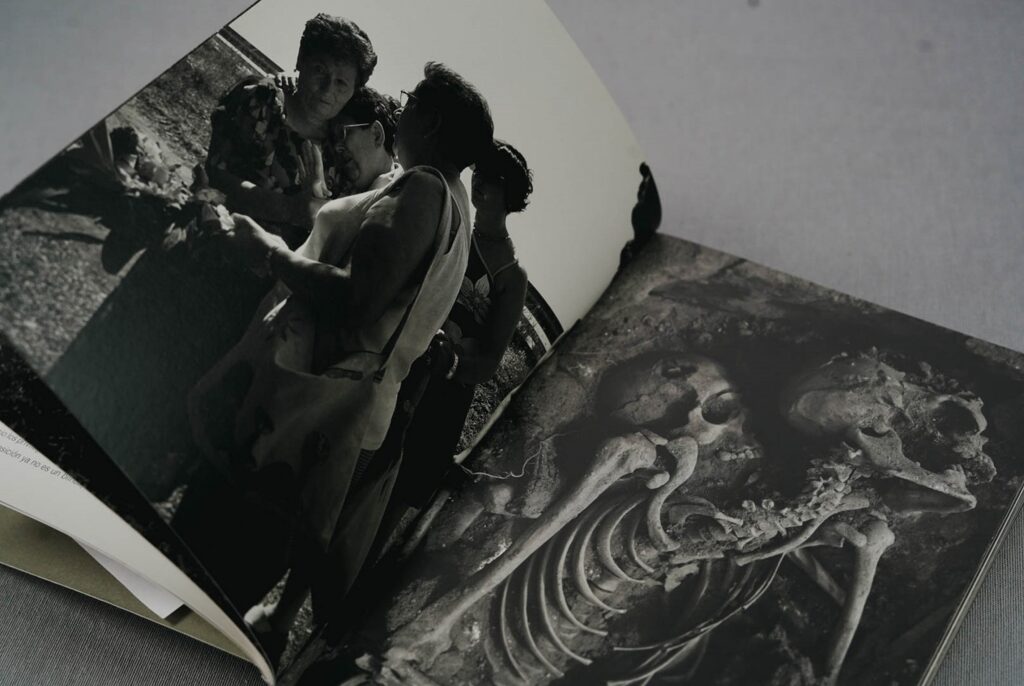

The boom in Spanish memory photography took off in 1999—much later than in film and literature, where the wave of historically-themed stories began in the 1980s. According to Antonio Ansón, the Spanish photographers who worked in the postwar years belong to the “generation of silence,” while those working during the years of the Transition, in the 1970s, can be identified as the “generation of oblivion.” Neither of the two addressed the Spanish Civil War, either out of fear or a need for distance. This changed around the turn of the millennium, almost coinciding with the first exhumation under the supervision of forensic experts, at the initiative of Emilio Silva, in Priaranza del Bierzo (León) in the year 2000. From that point on, Spanish photographers rediscovered the war as a central theme. As the earth was stirred, it seems, so was the photographers’ memory.

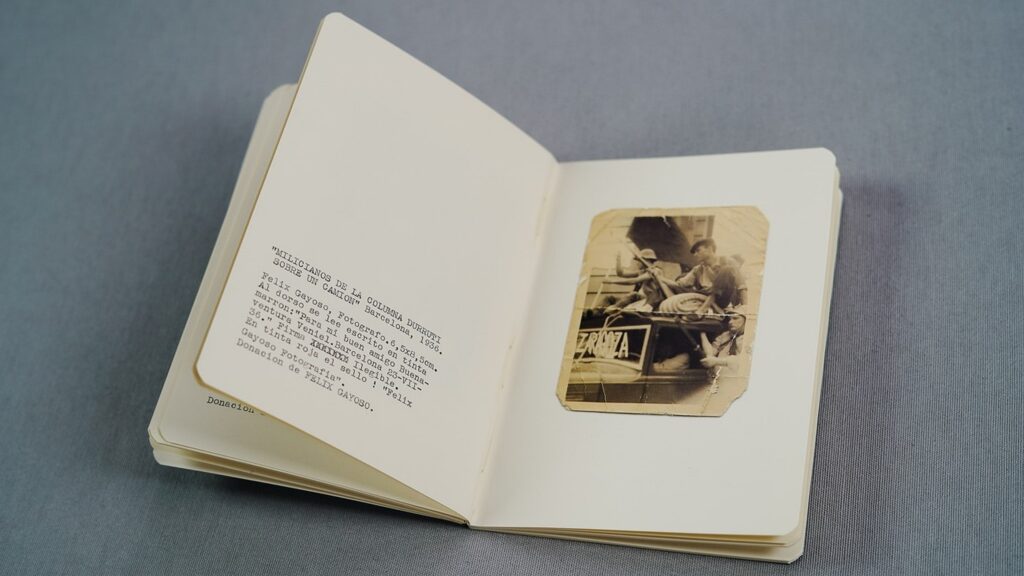

The first Spanish-Civil-War-themed photobook published in 1999, Memorias revolucionarias, is a rarity today. It is a small album of photos taken by Martí Llorens during the shooting of the Spanish Civil War film Libertarias (Vicente Aranda, 1996) in the streets of Barcelona. Llorens, moving around the movie set, shot the film’s extras and then treated the images to make them look old. In the book, these photographs are accompanied by fictional stories about the individuals portrayed.

In a sense, Llorens’ daring project, which straddles fiction and non-fiction, was twenty years ahead of its time, foreshadowing the photographic experiments that would emerge in 2019. The predominant trend during the first twenty years of memory photography memorialist was, by contrast, a sober documentary approach, as the generation of grandchildren of the Spaniards who lived the war, mostly born in the sixties, worked to make visible what for so many years had remained hidden from public view. They used photography to reveal Franco’s crimes and to give a face and a voice, and thus recognition, to the victims.

Many of these early projects, by artists such as Clemente Bernad, Francesc Torres or Montserrat Soto, focus on documenting the work of exhumation of mass graves. They use photography as a document: evidence in the face of impunity. Others, such as Ana Teresa Ortega, seek to identify the spaces of repression or travel through the landscapes of horror. Gervasio Sánchez, Sofía Moro, and others portrayed the victims and the disappeared, sometimes through their relatives. Still others, including José María Azkárraga and Juan Plasencia, focused on recovering the underground stories of the guerrilla, the maquis. Their projects are mainly thought of as photographic exhibitions, which we have been able to preserve thanks to the catalogs published. In a country where Franco’s crimes have not been judged and there has been no official recognition of the victims, these photographers have done crucial work to reveal—and fill—the gaps in the country’s collective memory.

Starting in 2019, however, a new generation of photographers, born in the late 1970s and early 1980s, begins to move beyond documentary forms. Rather than simply representing historical memory, they seek to reflect on its construction. And instead of trying to fill gaps, these photobooks reveal them in all their emptiness, embracing experimental processes that often resort to photomontage. They also tend to deploy a certain ambiguity, use games of dislocations and dissonances, be performative, and emphasize a subjective or autobiographical point of view that requires the active participation of the public.

While the documentalists’ work was primarily shared in exhibits and exhibit catalogs, these younger photographers prefer the format of the photobook, a medium that allows the reader to assume a more active, experiential role. It’s perhaps not a coincidence that this new approach emerged around the time of Franco’s exhumation from the Valley of the Fallen. Once again, stirring the earth stirred collective memory, albeit in a different way than it did twenty years earlier.

All the projects mentioned here, along with many others, can be found in the online Archive of Photographic Memory of the Civil War, the first website to recover, analyze, catalog, preserve and disseminate photographic practices of memory in Spain. The site includes a map and timeline of the different forms that contemporary Spanish memory photography has taken over the years, tracing relationships, legacies and breaks between the different projects, placed in the broader political and social context, including the Memory Laws of 2007 and 2022. The archive was first presented at the exhibition Ecos de la memoria. Fotolibros del presente, which took place at the Museu de Belles Arts de Castelló (València) between May and July 2023.

Marta Martín Núñez is a professor of Photography and Narrative at the Universitat Jaume I de Castellón, where she directs the Archivo de Memoria Fotográfica de la Guerra Civil.