From the Lincoln Brigade to Mauthausen: How an Anarchist Saved 300 Spaniards

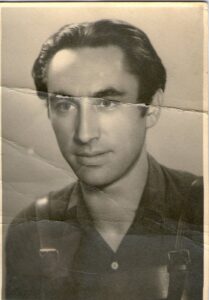

Despite their name, the famous International Brigades of Spain’s Republican Army included thousands of Spanish soldiers who served alongside the foreign volunteers. Among them was César Orquín, an anarchist from Valencia who served as a commissar in the Lincoln Battalion. Details of his extraordinary life, long shrouded in mystery and scandal, have recently come to light in Albert Montón’s documentary El Kapo (2023), based on research by Guillem Llin.

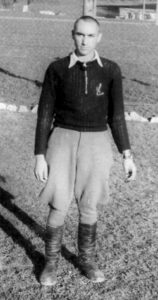

César Orquín Serra was born in 1914, the illegitimate son of an important Valencian aristocrat who gave him up for adoption to a middle-class couple. In 1935, César broke relations with his real father, who sent him to Africa to do his military service in the Spanish Protectorate in Morocco. While César was there, Franco staged the coup d’état that unleashed the Civil War. Although the rebellion succeeded in the area where Orquín was stationed, he managed to escape, arriving in the Spanish mainland by crossing the Strait of Gibraltar in a barge. He stopped in Valencia to see his adoptive parents and then volunteered to defend the Republic. Although his initial whereabouts are unknown, in 1937 he appeared as a political commissar in the International Brigades, in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion—nothing short of remarkable, given that Orquín was an avowed anarchist.

Toward the end of the war, when the rebel troops finally conquered Catalonia, Orquín followed thousands of Republicans into exile, crossing the French border at Le Perthus on February 7, 1939. In France, he was first interned in the Saint-Cyprien concentration camp and then, in the months following, passed through the camps of Argelès, Agde, and Le Barcarès. In late December 1939, he joined one of the Companies of Foreign Workers (Compagnies de travailleurs étrangers, or CTE) that the French government assigned to reinforce the Maginot Line.

After the Nazis invaded and occupied France in May-June 1940, most of the Spanish exiles enrolled in the CTE were taken prisoner. César Orquín found himself interned in Stalag V-D, in Strasbourg. In late 1940, he was deported to the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria, where he arrived by freight train on December 13. Since he spoke Catalan, French, German, English, and Spanish, he was employed as an interpreter. Using his powers of persuasion, he managed something highly improbable: he convinced the Mauthausen commanders to allow him to leave the camp with a Kommando of Spanish inmates to work on the construction projects that the outbreak of the war had left unfinished. At that time, in May 1941, the Mauthausen-Gusen complex had no subcamp. The Kommando of Vöcklabruck was the first of 50 or so that the central camp would come to have.

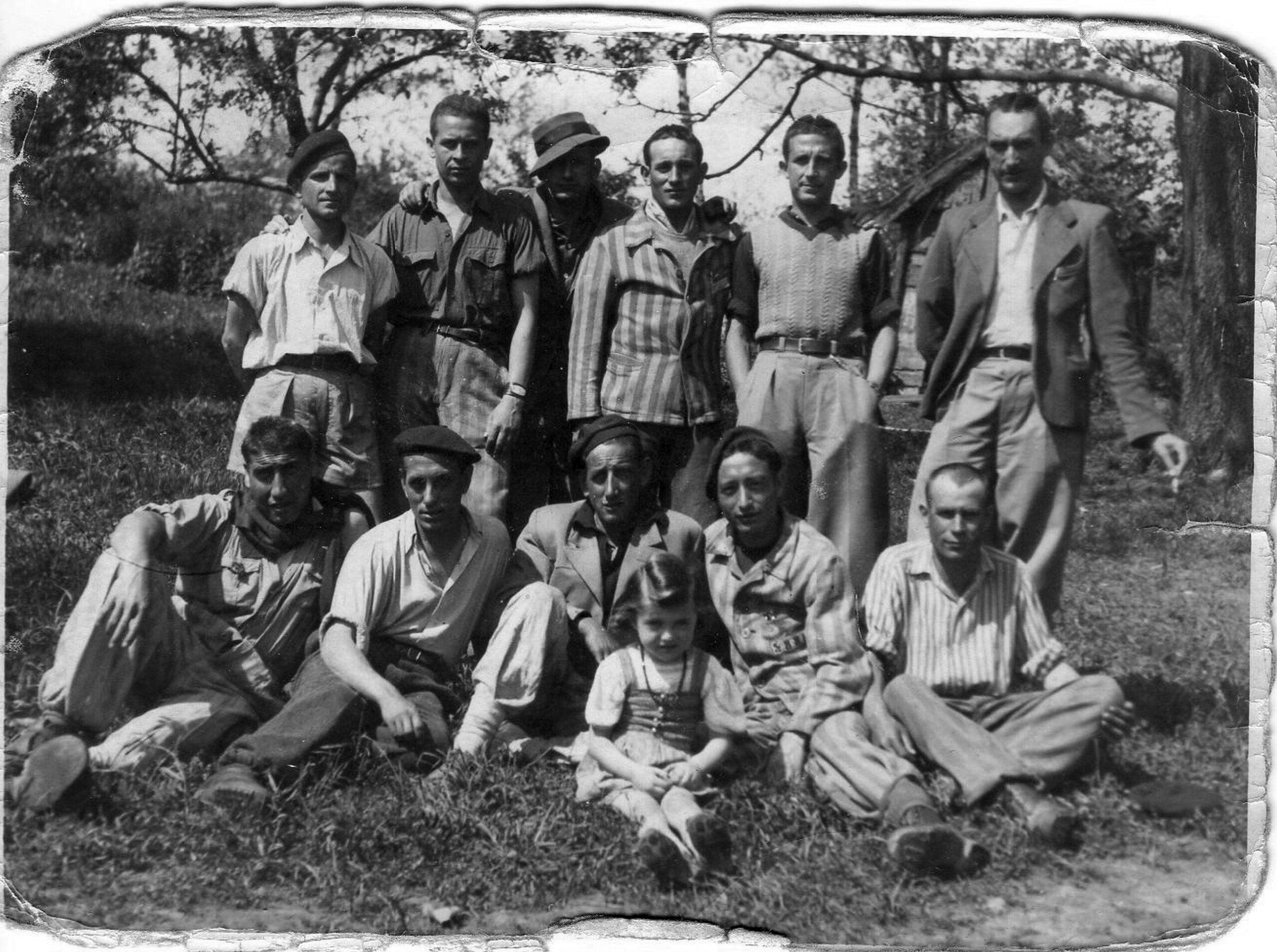

On June 6, 1941, the first convoy left with Orquín as commander or Kapo. It would be followed by other convoys up to a total of 336 deportees, all of them Spanish Republicans. They stayed in the Austrian town of Vöcklabruck until May 1942, when they received orders to move to Ternberg to build a power station at the Enns River. In the period that they were in Vöcklabruck not a single deportee died, which contrasts starkly with what was happening in Mauthausen and Gusen, where more than 3,000 Spanish Republicans perished. As Kapo, César managed to gain absolute power, to the point where he locked the barracks where the deportees slept so that the Nazis could not disturb his men, allowing them to rest.

While working at Ternberg, Orquín’s team built a dam on the river despite non-existent safety measures. Twelve or thirteen of the 408 deportees died, most of them from work-related accidents. How remarkably low this 3% fatality rate was we compared to a larger Kommando that worked 19 kilometers further upstream, also building a dam, with 227 deaths on a total of 1,013 workers.

Still, it was in Ternberg where Orquín’s relationship with the Communist Party, which had always been tense because of his commitment to Anarchism, gave rise to the distorted version of events that would haunt him ever since. The communists, who led the clandestine resistance movement among the Mauthausen inmates, sought to control Orquín’s Kommando. He not only refused but ignored them. The tension increased further when Orquín was ordered to return to the central camp because the needs of the war had changed. His Kommando sat in Mauthausen from September 18 to December 2, 1944, doing nothing, until Orquín was ordered to take about 300 Spanish Republicans to Redl-Zipf, to drill tunnels that could be used to produce ammunition for the German army. Orquín’s Kommando became known as the Kommando César.

The event that would tarnish Orquín’s postwar reputation most severely happened in March 1945, when the Nazis ordered 221 prisoners— including 96 men from the Kommando César—to be sent to the Gusen camp, where the death rate was astronomical. Later, the Communist Party claimed that Orquín had sent close to 100 of its members to their death. The truth was that all 96 deportees survived and were released when American troops liberated the camp on May 5, 1945. In the end, two out of every three Spanish Republican deportees would perish in Mauthausen. Of the Kommando César, only 3% did. Rather than sending them to their deaths, in other words, Orquín saved the men who worked for him.

After the war, harsh punishments were meted out to camp inmates who’d been employed as Kapos by the Nazis. Orquín’s days, too, seemed numbered—until, in a masterstroke, he showed up at the school building in Vöcklabruck that the municipality had left to the members of Kommando César in gratitude for the work done years before. When Orquín asked the deportees to give an account of his time in charge, their testimonies reflected their collective admiration and gratitude. The following year, Orquín and other former deportees founded the Organization of Spanish Republicans in Austria (OREA).

Not long after, in the face of continuing pressure, Orquín—by now married and with a young daughter— decided to emigrate to Argentina, where he lived until his death in 1988. In 1963, the Catalan novelist Joaquim Amat-Piniella, who had served in the Kommando César during the war, would include Orquín in his acclaimed autobiographical novel K.L. Reich as a character named August.

Guillem Llin Llopis (1958) is a self-taught historian whose research has informed El Kapo, a documentary about César Orquín coproduced by the University of Valencia (Spain) and the National University of Cuyo (Argentina).