Finding Ruby: A Memoir

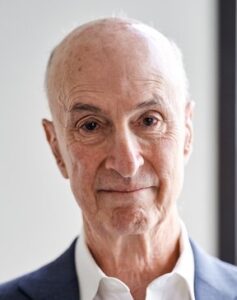

In his forthcoming memoir Finding Ruby, Richard Rothman explores the lives of two grandfathers of his who fought with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Rothman is Special Pro Bono Counsel to Weil Law Firm, where he previously served as co-head of Complex Commercial Litigation. In 2023, Rich was honored with the New York Law Journal’s prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award.

I’m the proud grandson of two Lincoln Brigade veterans—both on my mother’s side. I was named after Rubin (“Ruby”) Schechter. Ruby was shot in the arm at the battle of Brunete in July 1937. He died in a Madrid hospital in August. Harry Nobel, who knew Ruby from their pre-war days in Queens, N.Y., survived the war and later married Ruby’s widow, my Grandma Rose. So Harry was the grandfather I knew and loved growing up. Harry fought in the battles at Jarama, Brunete and Aragon, and later served in the U.S. Army during WWII.

I’ve spent the last five years trying to understand the fervent idealism that drove Ruby and Harry to leave home to fight in a perilous foreign civil war, and also the equally passionate, some would say blind idealism that impelled Harry and Rose to devote and sacrifice their lives to the Communist Party in the decades after Ruby’s death. This book is about the twisted path I followed in my quest to understand their idealism, and ponder my own.

Much of what I’ve learned came out of a battered black leather briefcase that had gone missing for forty-five years since I first came across it as a young man, until my wife found it buried in the back of a closet in my mother’s apartment after she died. The elusive briefcase contained scores of letters written by, to, and about Ruby during his days in Spain before and after he was shot.

A short biography of Ruby in the briefcase revealed that Ruby had left a letter for his parents telling them that he’d gone to Spain to fight against fascism (leaving his wife and five-year-old daughter, my mother behind). His letter warned them: “If you ever want to see me again don’t trouble yourselves and turn to anybody; don’t consult any lawyers!” He assured his heart-broken parents, however, that he would have an office job and would be nowhere near the fighting, so his life would not be in danger.

And Ruby did have an office job: My grandfather was the Battalion Secretary of the Washington Brigade, which was merged with the Lincoln Brigade after both brigades were decimated during the battle of Brunete. But my grandfather quickly forgot the promise he’d made to his parents. He joined the fighting on the front lines and, as his letters reflect, he did so with relish. The letters reveal him to have been an enthusiastic, morale-boosting, and brave, if not reckless, soldier. They also show he was a gifted writer with a keen sense of humor, and a hopeless romantic.

Here are a few excerpts from the book, beginning in May of 1937 as Ruby trained for the battle ahead—after a harrowing winter hike over the Pyrenees at night to get to Spain in violation of FDR’s edict prohibiting U.S. citizens from participating in the war:

The New Masses Article

Upon first leafing through the documents in the briefcase, I’d been surprised to discover several fragile broadsheet newspaper pages containing an article with typed versions of four letters Ruby had written to Rose from Spain (slightly edited, with mushy parts removed). The article appeared in the October 1937 edition of New Masses magazine—two months after Ruby died.

New Masses was a Marxist publication closely associated with the Communist Party that ran from 1926-1948. It was named for a predecessor Marxist magazine, The Masses, which was published from 1911 until 1917, when it was shut down by the U.S. government for opposing World War I. New Masses was launched in 1926 by a group of artists along with the Communist Party as a magazine “dedicated to a radical perspective on art and literature.”

The article in the October 1937 edition was entitled:

FOUR LETTERS FROM SPAIN

What an American in the fighting forces there thinks about is clearly shown in what a seasoned revolutionist wrote to this wife

Preceding the excerpt of the published letter was a biographical paragraph that began:

Rubin Schechter, who wrote these letters to his wife, died on August 28, 1937 of the wound he describes. Schechter was section organizer of the Communist Party in the Third Assembly District of Queens County, N.Y. when he went to Spain. … One of his outstanding pieces of party work in Queens was with the Committee for Equal Opportunity, which fought through to a successful conclusion its campaign to end the Queens County General Hospital’s discrimination against Negro Doctors.

It’s no wonder that of all the letters Ruby wrote to Rose from Spain, his May 12th letter was one of the four she or the publisher decided to print. I found it not only revealing but funny, in a tragic way, as my grandfather extolled the superiority of the soon-to-be decimated Republican army:

Our training has taken on a spurt in the past week. We are rapidly shaping into a competent battalion under the marvelous leadership of a “Mexican” brand of commander. We are being trained not in the bourgeois ways—their way is to work away at a man until they have turned a thinking human being into a blind, brutal mechanism. Our way is to develop military understanding through open discussion and lectures. Every soldier is taught in such a way that he is able to understand and think alongside of his officers. We never say “Do this!” We always say, “The following is our purpose today. In order to achieve this, you can do it best in the following manner.” Of course this takes longer, but your soldier remains a dignified, thinking person. He grows in understanding and flexibility. A dangerous situation is something for him to think about and solve to the disadvantage of the fascist enemy ….Our army is superior to the fascist armies because its man-power is free. It follows, of course, that victory must be ours.

I chuckled to myself as I envisioned the “comrades” having a group discussion debating whether to stand their ground or retreat while the Fascist soldiers were following orders to mow them down. I would come to learn, however, that this was no laughing matter, given the disconnect between Ruby’s glowing, optimistic portrait of his “superior” battalion, and reality.

***

The Battle of Brunette in which Ruby was wounded, began on July 6, 1937. The Republican army’s major offensive, including more than 70,000 soldiers, was a surprise attack intended to divert Franco’s fascist army from its drive to Madrid, about 15 miles from the otherwise strategically irrelevant village of Brunette. The Republican forces, including the Lincoln and Washington Brigades, had some initial success, but the battle had turned by the time my grandfather wrote to his wife on July 21st. Here’s an excerpt:

Ruby’s July 21st letter to Rose was the second of the four letters published in New Masses magazine two months after his death. Written four days before Ruby was shot, this one is another combination of fantasy—as Ruby spoke optimistically and tried to put a good face on things as the Brunete offensive cratered—and a brutally realistic depiction of the war.

Darling/Sweetheart You have heard of our attack. The Lincoln and Washington Brigades took decisive parts in the great offensive. Right now we are participating in a few defensive actions. But not defensive in the old sense, the sense of stopping a fascist advance. We are holding and fortifying positions which we have already captured. We are fortifying our offensive. On other fronts, of course, we keep advancing. …We have struck deep into the vitals of the despoilers of humanity. Soon fascism will be in flames.

My grandfather’s statement that his brigade’s defensive actions were “not defensive in the old sense, the sense of stopping a fascist advance”—and that they were “fortifying our offensive”—might have been technically accurate at that moment, as the Republicans probably were still attempting to cling to their initial gains. But not for long, as the Nationalists and their Nazi allies bombarded the Republicans with massive air and artillery attacks. Ruby’s July 21st letter proceeded to vividly capture the experience of being bombed and strafed:

I write these general lines during these moments when everything is far from general. Twice during the course of these few sentences I have had to stop and quickly flatten out to keep out of the sight of planes, (In this case they proved to be our own planes.) Everywhere the bullets are whistling and crackling.

Right now our artillery is raising hell with fascist lines. But almost daily we have experienced the crashing and smashing of their artillery. And as they have tasted of our serial bombardments, so have we of theirs. I can say with all pride I can summon up that our battalions have been subjected to two of the severest and most dreadful bombings from the air, and that we came out of them with flying colors; not a scratch on our morale.

After finishing an early draft of this book, I read Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. I thought I’d read it decades ago, but quickly realized that I hadn’t. That’s because had I read Hemingway’s riveting story of the horrors of the Spanish Civil War I wouldn’t have labored under the misimpression that it wasn’t much of a war. But about the bombings, Hemingway’s lead character, Robert Jordan, had this to say: “The damned planes scare you to death but they don’t kill you. …Those things never kill anybody” (p.323).

My grandfather’s July 21st letter provided a similar assessment of the aerial bombings in Spain, which were making their first warfare appearance long before targets could be spotted with precision. My grandfather focused, in particular, on the psychological dimension of the horrific bombings and their effect on morale:

As for loss of life, there is this to say about artillery and aerial bombardment: there must be a direct hit in order to do real damage. Aerial bombardment rarely gets many. It is successful if it manages to shatter the nerves and morale of those who are subjected to the bombardment. Strafing by planes is also of the same nature.

The greatest loss of life still comes from the machine gun and the rifle; it still comes from men who face each other almost within sight of each other and shoot one another. In the final analysis, planes, artillery and tanks too are auxiliaries to the soldier with his rifle and to the machine gun crew. They are peculiar auxiliaries in that they seem to dwarf the man with the rifle and even the machine gun crew. The most fearful electric storms with bolts of lightening, crashes of thunder, and sheets of rain do not give such a feeling of man’s helplessness and tininess as the smashing and crashing and tearing and earth ripping and deafening rips of thunder from which all silence has been torn out of the aerial bombardment.

Darling, the last sentence I finished one hour after I started it. During this time we were subjected to a terrific aerial bombardment plus strafing. Again the damage is almost unmentionable. But how can you fight this horror? In no way at all. You lie prone, your face buried in the dirt, your body elongated, you clutch onto something. You wait. When it is over, comrades begin to raise their heads toward each other and a smile begins to flicker and spread. The curse words begin to be heard and they also spread. Then the tension snaps. Some begin to look around for the hurt. Others begin to tell their feelings and, of course, how very close they were from a bursting bomb.

You can see, darling, from what I have just said (and even from the slant of my writing) that it is extremely difficult to write under our present conditions. However, I must write just as often as possible so that you can see my writing and know that I am well.

Permit me to finish off. Perhaps some other time (when I can recollect many emotions in tranquility) I shall be able to tell you how often and beautifully you appeared in my thoughts in these hours of trial. I can only tell you this thing to make you happy: I have never once been afraid.

Here is my kiss for Toby [my mother]. My love. Salud!

Ruby

As I reflected on the fact that Ruby wrote these letters hurriedly, in a single draft, while in the midst of being strafed by Hitler’s bombers, it struck me that my grandfather was a talented writer and a rather remarkable character. …At the same time, my grandfather was hardly a realist, and the vaunted Brunete offensive was on death’s doorstep as he wrote his July 21st letter. Moreover, at Brunete as elsewhere, Franco was not content merely to win the strategically irrelevant real estate being fought over there. As Paul Preston has written:

Franco’s notion of a war of moral redemption by terror did not permit him to give up an inch of once captured territory nor to turn aside from any opportunity to hammer home the message of his invincibility in Republican blood—whatever the human cost to his own side. Brunete offered an irresistible temptation to annihilate large numbers of Republican troops

And he did, annihilating over 20,000—including my grandfather.

***

My grandfather was wounded on July 24th—the day the Nationalists took control of Brunete. He wrote to Rose the next day from the hospital in Madrid, assuring her that there was “nothing to worry about” because “the bullet went clean through the upper fleshy portion of the arm and did not touch the bone, which means quick healing and I ought to be back with the Battalion within 15 days.” That’s not what happened, as he described in the letter he wrote to my grandmother three weeks later—the last of the four letters published together in New Masses after Ruby’s death. Written on August 12,1937, still using his left hand, this letter put my grandfather’s personality on full display—his blind idealism and optimism, his sense of humor, and his flair for writing:

Wounds are stubborn things…. If it were just a matter of where the bullet passed through, I would be ready to return to the front any one of these days, so well healed are the punctures. But it’s the partial paralysis in the fingers … which takes time and sometimes very painful waiting—until the torn nerves repair by themselves or if possible are repaired by the surgeon’s skill.

Ruby then proceeded to give my grandmother a blow-by-blow account of how he was shot. But for the fact that he wound up dying from the wound—and, even despite his demise—on one level, it struck me as hilarious:

Because I am not certain as to whether you received my last letter I will repeat to you that I was shot through the right arm (above the elbow) on the 24th of July a little before sundown. It was on the now famous Brunete sector. How did I come to be wounded? It was on account of a mule (still one of the chief methods of transportation in this land).

Our battalion was re-advancing to a position which for strategical reason we had temporarily retreated from. We had not gone 800 yards when we bumped into a fascist military patrol. Naturally, we strung out and started to go to work on the ditches. But we were short on ammunition and I started back for ammunition to our temporary base 800 yards back. I got there, loaded a dark skinned donkey with four cases of bullets and started towards our fighting comrades. But the donkey had his own idea of how fast to go, and he deliberately proceeded to stroll leisurely down this field of whistling bullets as if it was Sunday on 5th Avenue. I spoke to the donkey in my best English (I had too much to tell him to say it in Spanish). I said to the donkey:

“See what a damn fool donkey you are. You think your dark hide will save you. You think you are camouflaged. But no one is aiming at you in particular. See how the bullets are coming in all directions. If you really had sense we could take this gap on the run. The comrades will not believe their eyes if you come tearing up with their ammunition. They will positively adore you. You will be a donkey such as never was—on sea or land. This argument does not move you because you are a typical product of the old order. You prefer to drag along at the pace of all your fathers, when some real speed would give us both a glorious lease of life. As it is you will probably be the death of both of us. That is where you conservatives always lead us to.”

So I spoke to this unreasonable donkey. And you may believe me the donkey supplied me with plenty of time to say these things. Nor was he a bad listener; his only fault was that he merely listened. And so it came to pass that it was no more than thirty seconds after I delivered myself of this exhortation that one of those countless bullets swished—shot through my arm and I am forced to drop to the ground, shouting aloud for first aid. A Spanish comrade, stooping very low came quickly to me and speedily applied the first aid bandage we all carry with us. You may rest assured that I did not let go the reins of the silly donkey. I turned him over to another comrade who came stomping by, with instructions for him to lead the donkey all the way around to the right and then to the battalion, since there was no way of making him run straight there. I also took care to take all the battalion records from my knapsack. Then, assisted by the Spanish comrade, I cautiously and safely made my way back to our temporary base, where I delivered the papers to the proper authority and myself to the medical stations.

You must know darling that I am not able to write much more. I must revise my estimate of my return to the front. Perhaps it will be another month before I return.

There were no further letters. Ruby died in Madrid three weeks later. His profile in the Lincoln Brigade Archive records: “d August 24 (30), 1937 from wounds and was buried at Murcia.” We never had any information as to why Ruby died after being shot in the arm, and we surmised that the cause of death was an infection that would not have been fatal today and, even then, shouldn’t have been lethal. Decades later, my grandmother claimed that he had been murdered by Trotskyites in the Madrid hospital, with his corpse found in a basement by two fellow Lincoln vets who came to visit and instead proceeded to bury him. Hard to believe, but hard to make up. I’ll never know the truth.