Book Review: Portuguese Anti-Fascists in Wartime Madrid

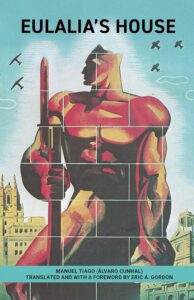

Manuel Tiego, Eulalia’s House. Translated by Eric A. Gordon. New York: International Publishing Company, 2022. 160pp.

Manuel Tiego, Eulalia’s House. Translated by Eric A. Gordon. New York: International Publishing Company, 2022. 160pp.

It’s a well-known fact that Hitler’s and Mussolini’s illegal support to Nationalist rebel forces during the Spanish Civil War was essential to Franco’s victory. Yet the more discreet assistance provided by Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, Portugal’s reclusive right-wing dictator from 1922 until 1968, is often overlooked. Even less attention has been paid to Portuguese citizens working in Spain to defend the legitimate Republican government. Eulalia’s House, a neorealist novel set among Portuguese anti-fascist activists in Madrid, is an important correction to this oversight. A lightly fictionalized account of the early months of the war, it offers a fascinating insight into the particular dilemmas of this unique group of comrades, illuminating their insider/outsider status with authenticity.

The novel’s author Álvaro Cunhal led the Portuguese Communist Party for nearly half a century. He spent most of his adulthood either underground, in exile or incarcerated, using his years in solitary confinement to reflect on his life in struggle through fiction, yet concealing his writing identity well into old age through the pseudonym “Manuel Tiago.” Publication was impossible in Portugal until after the 1974 Carnation Revolution which ended the brutally repressive Estado Novo regime inaugurated by Salazar. Two years later, Irwin Stern, in an article about suppressed and censored twentieth-century Portuguese fiction, praised the originality of Tiago’s themes in the now seminal Until Tomorrow, Comrades, but not his literary style, and identified Cunhal as the model for its protagonist but not as the novel’s author. That book, published in English for the first time earlier this year, completes Eric Gordon’s commendable project to translate every one of Cunhal’s eight works of fiction.

Of these, Eulalia’s House is the only novel set entirely in Spain. It opens immediately before the right-wing coup of July 1936, when the capital is “a boiling volcano.” Three young Portuguese political emigrés consider their options in the event of war. António is a part-time car mechanic, but his more important work is for the Party and International Red Aid (Socorro Rojo Internacional), conveying comrades clandestinely back and forth across the Spanish-Portuguese border, soon to close. One such comrade is Manuel, a youth movement leader who has recently escaped capture in Lisbon. He is committed to action, no matter what. António has brought him to the eponymous safe house in Madrid run by a beautiful miliciana called Eulalia, where her generous, warm-hearted mother, known to all as Madrecita, cooks, cleans and takes care of the exiles. António and Manuel’s companion Renato, in hiding since taking part in a major strike in Portugal in 1934, has come to Spain with his wife “to stay out of trouble.”

The novel’s spare, economical narrative moves constantly between the general and the particular, placing these three characters firmly in the context of historical events as they unfold. It alternates between accounts of specific moments of spontaneous and well-organised resistance to the coup—relishing the power of the camaraderie which made such resistance possible—and António’s tormenting internal dilemmas about his personal role in this crisis. Should liberation and revolution in his native Portugal be his first priority? Must he simply obey Party orders, no matter what, and content himself with work behind the scenes? Or should he, like Manuel and Renato in their different ways, prove his courage to himself and to the world by committing fully to the Spanish cause and heading for the front line?

Other characters, less clearly delineated, tend to represent political positions or types. António’s various motor vehicles are perhaps better characterized than most of the novel’s female figures, who rarely escape stereotyping. Eulalia’s first introduction as “a mixture of maternal tenderness and the coquette,” an iteration of the reductive Madonna/whore dichotomy, says more about the man describing her than the woman described. Eulalia herself, whose only imperfection is apparently an attractively twisted front tooth, is seen only fleetingly. Off-stage, she eventually becomes a political commissar in the People’s Army, leaving Madrecita sadly longing for news.

Cunhal conveys the charged atmosphere in the capital and beyond with gripping and convincing detail. Yet there is often a sense of action taking place at some remove. Events and ideas tend to be recounted through conversations. A slight syntactical awkwardness and the dependence on the passive voice may reflect the language in which the characters speak, “a mishmash of half Spanish, half Portuguese” which “everyone” could understand. “Everyone” is almost a character in its own right.

These distancing devices underscore a major theme of the novel: the tensions experienced by the Portuguese who sympathized with the Spanish Republic. According to Cunhal, they could blend in with ease (certainly compared with most American Brigadistas), but couldn’t necessarily enjoy full assimilation. Most Spaniards welcomed them as equals, companions in a collective, international endeavour; others treated them as outsiders with ulterior motives, as objects of suspicion. The Portuguese, who had no national battalion, could serve and mix as easily in the Republican Army as in the International Brigades. In either case, their names were frequently recorded with Spanish spellings. Individual and national identities vanished easily, like stretcher-bearers under battlefield fire.

Eulalia’s House is a quick and thought-provoking read, valuable particularly for the window it opens onto a complex history that, for English-speaking audiences, has been inaccessible for far too long.

Dr. Lydia Syson is the author of A World Between Us, a novel set during the Spanish Civil War, which introduces the International Brigades to young adult readers, and Liberty’s Fire, a fictional account of the 1871 Paris Commune. She is currently working on a biography of her anarchist great-great-grandmother, N.F. Dryhurst, who was a friend and translator of Kropotkin and a founding member of the Freedom circle.