Ben Shahn Returns to Spain, or the Intangible and Untimely Heritage of Anti-Fascism

Cover of Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity, exhibition catalogue, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, 2023.

We talk about the “return” of Picasso’s Guernica (1937) to Spain, even though that massive painting had never been there before its “repatriation” in 1981. The magnificent exhibition Ben Shahn: On Nonconformity, curated by Laura Katzman and on display until February 26 at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, elicits a similar sense: an arrival that feels like a return, a journey abroad that is a homecoming.

First, we undo the knots in the massive rope of history. Then we unbraid the rope itself, teasing apart the strands of lived experience. We later display single spindly filaments as if they were somehow history or life itself.

Painting here; photography over there; sculpture, someplace out of the way where we won’t bump into it; pamphlets and posters, somewhere else yet (as far away as possible from the serious stuff, please). Magazines and newspapers, in the flea market, or in the recycling bin or landfill. Books, tucked away in the stacks like so many dead in their call-numbered niches.

Sacco and Vanzetti? In the KF section, sixth level. Haywood Patterson and Jim Crow lynchings? In the E section, third level. Leo Frank and antisemitism? In the DS section, level four. Guernica? Guernica? Off-site. You’re in the wrong cemetery.

Or are you?

***

Ernest Hemingway created what has become for many the iconic portrait of an American volunteer in the Spanish Civil War. Robert Jordan, a taciturn loner, the rugged WASP outdoorsman from Montana. But Ernest knew better.

In Spain, Hemingway got to know a fair number of the real 2,800 women and men who would volunteer to fight fascism in Spain some five years before Pearl Harbor, earning for themselves the Cold War epithet of “premature anti-fascists.” (As opposed to “timely” or “tardy” anti-fascists, one must presume.) Hemingway knew how the volunteers were mostly children of immigrants or immigrants themselves, raised in the teeming Depression-era ghettos of major U.S. cities. He knew that, unlike Robert Jordan, who seems to materialize out of thin air onto the austere meseta of war-torn Spain, these volunteers emerged, like the visible part of an iceberg, out of vibrant and vast mobilized working-class communities. Communities sensitive to injustice, seasoned in solidarity and collective action, indifferent to borders. Hemingway knew—or should have known—that for every woman or man who walked across the Pyrenees into Spain in cardboard-soled shoes, there were tens of thousands of fighters back home, who saw Braintree, Massachusetts, Scottsboro, Alabama, Flint, Michigan, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Belchite, Spain, as battlegrounds in a single war. Their war.

Ben Shahn (1898-1969) is perhaps best seen as a rank-and-file member in this army of anti-fascist volunteers for freedom. A brigadista internacional who fought elsewhere and otherwise. This becomes clearer than ever when his work is exhibited in the same building as Picasso’s Guernica.

***

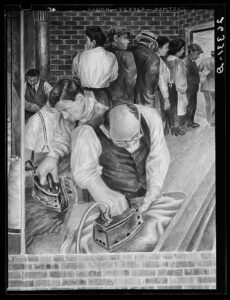

Arthur Rothstein, Detail of mural painted by Ben Shahn at the community building, Hightstown, New Jersey, 1938. FSA-OWI Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

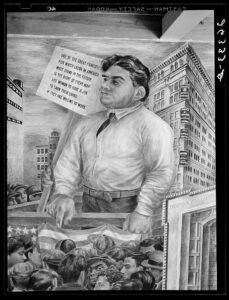

Arthur Rothstein, Detail of mural painted by Ben Shahn at the community building, Hightstown, New Jersey, 1938. FSA-OWI Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

Direct references to Spain appear periodically, as far as I can tell, in Shahn’s work. His love of Goya comes through in some pictures and prose. In his advice to young artists, he urged them, in addition to working as potato farmers or grease monkeys, to travel “to Paris and Madrid and Rome and Ravenna and Padua.” There are some newspaper images of Spanish Civil War refugees in his source files—pictures that inspired at least one of his major paintings about the horrors of World War II. And of course, we don’t know how many times he may have stood before Picasso’s Guernica all those years it was on deposit at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA.) We do know that Alfred H. Barr, Jr. invited Shahn to participate, alongside Stuart Davis, Juan Larrea, Jacques Lipschitz and José Luis Sert, in the famously contentious symposium on the “meaning” of Picasso’s painting, which was held at MoMA on November 25, 1947. Shahn, who greatly admired Picasso, attended the conference, but made few comments. He mostly critiqued Guernica’s abstract style, which he believed would prove ineffective in speaking to future generations about the Spanish Civil War. It is not clear how much Shahn weighed in on the epic debate over whether the bull or the horse was meant to be Francisco Franco.

And yet, to the discerning eye, signs of Spain are everywhere in Shahn’s career, in his archive. Like this undated note from a certain Joe Vogel:

Dear Ben,

I saw Lou and he told me that you were in town but I couldn’t locate you. I am sorry to hear Ezra was ill. I should like to see you next time you get here.

I got back on September 8th. Am feeling good except for an ulcer duodenal –Am going to see a doctor today.

I saw a photograph of yours at the World s Fair in Paris Exposition.

My Leica got lost at the front but who cares –I was too busy to look for it.

Lou told me you are going to do a fresco job in Hightstown –also that you might need a plasterer etc.

Could you get me something –as I am absolutely broke –I may and may not get on the WPA.

I have lots of material to work from and if I get an opportunity I’ll get down to work right away.

I hope to see you soon in NY. Best regards to Bernarda,

Joe

Ben Shahn, The Riveter (mural study, Bronx, New York central postal station), 1938. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Joseph Vogel had been Shahn’s assistant on the ill-fated Rikers Island mural (1934-35). This Polish-born photographer-lithographer-draftsman shipped off to Spain in January of 1937 to join the International Brigades; he returned to New York aboard the SS Paris in September of that same year, broke, Leica-less, ulcer ridden, and in dire need of work. He most likely saw the Paris Exposition on his way to Spain in January; had he gone to the Exposition on his way home from Spain he probably would have mentioned to Shahn having seen Picasso’s painting, which had been installed over the summer. Of course, in Madrid and on the Córdoba front, Vogel would have already seen quite a few of his own Guernicas— “lots of material to work from” is a haunting turn of phrase. And soon enough, he would be haunted by even more horror; Vogel would be among the military photographers who documented the liberation of Auschwitz in 1945.

Before leaving for Spain, Vogel published several works in Art Front, the journal of the short-lived Artists’ Union, as did a few other artists, who would also end up in Spain in the International Brigades, such as Judson Briggs and Phil Bard. Some issues of this publication have survived in the Ben Shahn papers at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. Shahn was an early editor and designer of the journal, to which he contributed his own satirical illustrations and Leica photographs of artists demonstrating for work relief. He was deeply invested in the interconnected issues of art and politics expounded and explored by Art Front. Shahn’s partner and collaborator, the artist Bernarda Bryson, was secretary of the Artists’ Union, which created and sponsored the publication. On the pages of Art Front, even before 1936, Spain is everywhere. Until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July of 1936, most of the artists in the Art Front circle were “Against War and Fascism.” (Shahn helped rewrite and signed the “Call” for the first American Artists’ Congress Against War and Fascism.) But after the coup led by Franco and supported by Hitler and Mussolini, many of these artists would drop their opposition to war, at least to this particular war. Spain, they came to hope and dream, would be the tomb of fascism once and for all. Alas, it wasn’t.

Tragically enough, though, Spain would be the tomb of roughly a thousand American anti-fascist volunteers. This included a remarkable number of artists and writers, such as several cultural workers from Ben Shahn’s circle who are prominently featured in texts and images on the pages of Art Front.

Take for example, Paul Block, a sculptor and one of the founders of the Artists’ Union. His eulogy appears in the October 1937 issue of Art Front.

In the town of Azuara, near Belchite in the Spanish province of Aragon, a mound of fresh-turned earth covers the body of Paul Block, sculptor and American soldier of the International Brigade… Paul Block was one of the ablest leaders of the New York Artists’ Union… It was he who conceived the idea of the Public Use of Art Program, a program which has already enabled the New York Union to bring government sponsored art to a popular audience increased by thousands, and which is the essential groundwork for the wide plan for a democratic American culture… We know that Paul fought for his fellows in Spain with the same zeal and brilliance that characterized his work for his fellows in America. We can best pay tribute to him by giving our energies to the objectives for which he worked and died. It is by virtue of the efforts of those who share the qualities so richly present in him that success will come in the struggle for democracy in Spain and for a democratic culture in America. (Oct, 1937).

This obituary is accompanied by a portrait of Block drawn by C. Yamasaki, a photograph of a piece of sculpture by Block, and a remarkable postscript, that further underscores the seamlessness of the lives of art and commitment led by this extraordinary circle of cultural workers.

Word has come that four other members of the Artists’ Union have given their lives in the fight against fascism in Spain: Sid Graham, Malcolm Chisholm, Jim Lang, Van der Vost. Graham and Chisholm were recruited into the Artists’ Union by Paul Block in Spain.

While in the trenches of Spain, Paul Block was recruiting for the Artists’ Union back in New York! Different battle, same war.

Art Front gave extensive coverage to the first strike organized by the union that Paul Block so ably led before shipping out to Spain. Though not printed in the magazine, the Smithsonian Archives of American Art holds an iconic photograph of that strike featuring, on the front line of the march, a handsome bushy-haired student of drawing and painting at the Art Students League: Edward Deyo Jacobs. Jacobs’ best friend, his fellow artist Doug Taylor, is almost certainly also somewhere in the crowded photograph, or perhaps just out of frame. Jacobs and Taylor were inseparable in the U.S. Some two years after the historic job action immortalized in the photograph, they both enlisted in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. In Spain they would prove to be inseparable as well. The two of them served as mapmakers in the Mackenzie-Papineau battalion, and they both disappeared during the chaos of the Ebro retreats. Witnesses report that Jacobs sprained an ankle during the frenzied flight from the fascists, and that Taylor refused to leave his side. They were never heard from again. A fellow volunteer, Len Levenson, recalled how somewhere in Spain, Jacobs and Taylor had acquired a large heavy volume of Goya etchings, which “they lugged in and out of combat, and which served them as a constant source of reflection and discussion.”

***

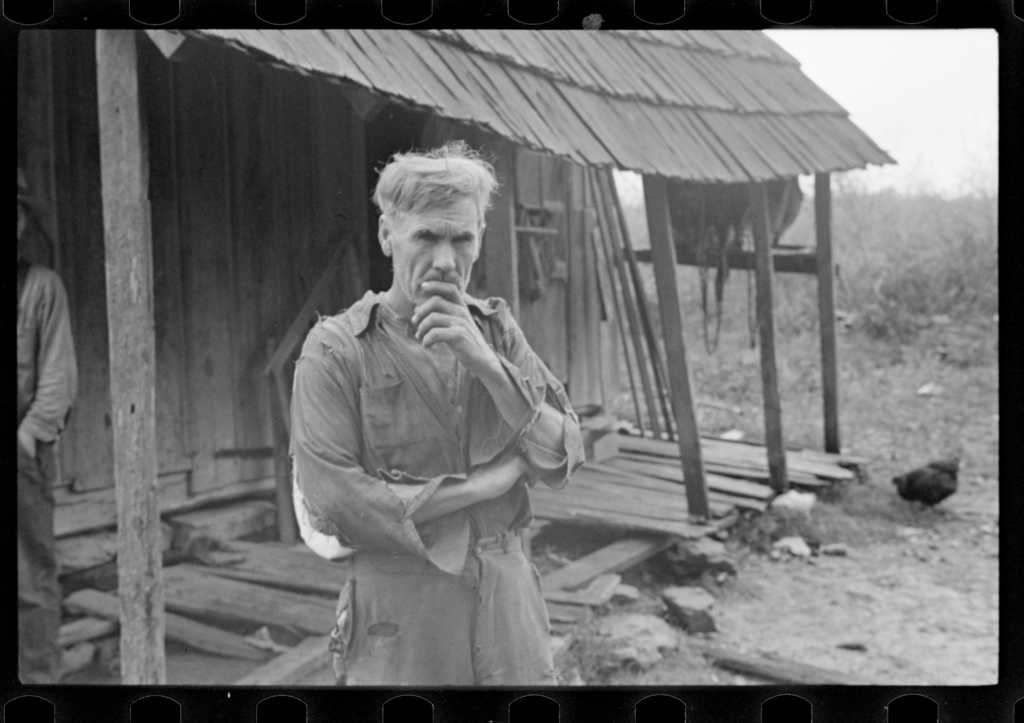

Ben Shahn, Sam Nichols, tenant farmer, Boone County, Arkansas, October 1935. Digital file from 35 mm negative. FSA-OWI Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

Joseph Vogel; Judson Briggs; Phil Bard; Lou Block; Edward Deyo Jacobs and Doug Taylor: all of these cultural workers emerge from the same milieu as Ben Shahn. In fact, these figures practically constitute a gallery of portraits of the kind of omnivorous creative person that Shahn called for in the almost Terentian advice he offered to young artists in the 1956-57 Eliot Norton Lectures he gave at Harvard. Published with the title The Shape of Content, it is as if Shahn were saying throughout these talks: “I am an artist, and as an artist, nothing human is alien to me.”

Go to college and go to an art school, or to two or three of them. Travel to Paris, sure, but also travel to Alabama. Ignore national borders, because ideas and injustices and rays of light do just that. Learn as many languages as you can. Work as a potato farmer or as a grease monkey. Get down and dirty. Live art. Smell, feel, taste, hear and see everything you find in front of you. Put yourself in front of all manner of things. Shun sterile and sterilizing distinctions: between high and low; producer and consumer; abstract and figurative; propaganda and art: education and art; art and life itself. “Never be afraid to become embroiled in art or life or politics; […]; and never be afraid to undertake any kind of art at all, however exalted or however common.” Remember, Shahn seemed to say, that a paintbrush, a chisel, a trowel or a Leica are all just tools of your trade, but so too is a megaphone, a typewriter or a picket sign.

In 1937, Vogel, Briggs, Bard, Block, Jacobs and Taylor took the extraordinary –but logical– step of adding to Ben Shahn’s anti-fascist toolbox, a rifle. And now, 85 years after the apparent end of the conflict in Spain, Shahn has reported to duty on the Madrid front in the on-going battle against fascism.

James D. Fernández is Professor of Spanish at NYU, director of NYU Madrid, and a longtime contributor to The Volunteer.

Reference: Laura Katzman et al., Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2023), 20-27, 56-58, and 90-95.