When Did World War II Start? And When Will It End? Reflections inspired by Guernica [part 2]

A view of the tapestry based on Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica”, which is on display outside the Security Council chamber at UN Headquarters. 14/Feb/2005. UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe. www.unmultimedia.org/photo/

When a visit to Picasso’s Guernica in Madrid was canceled because of Covid, James Fernández instead delivered this lecture. This is the last of two installments.

Throughout the summer and fall of 1936, indeed, for the duration of the war, Spain would be on almost everybody’s mind and retina in the US, whether they liked it or not: even escapist Depression-weary moviegoers who bought tickets to see Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936) or Victor Fleming’s The Wizard of Oz (1939), would be regaled with pre-show newsreels that, with melodramatic music and foreboding narrations, depicted the horrors of a new kind of modern warfare being debuted and perfected in Spain. Those much-celebrated innovations in the field of aviation—which in the 1920s and early 30s had fueled optimistic dreams of a more connected and peaceful world— gave way to the nightmarish scenes projected in darkened movie houses all over the world; of the bombers of the Condor Legion—the same planes which soon would be flying over London —dropping their eggs of death on horrified Spanish civilians, who look skyward, cursing their unknown assassins: “watch and listen,” booms the newsreel narrator, “as death rains down from the sky on the defenseless civilian populations of Madrid, Barcelona or Guernica.”

These same interwar years also ushered in technological innovations in the production and dissemination of images that would make the war in Spain one of the most spectacularized events of its time.

Relatively small cameras using better and faster film stock—like those used by Gerda Taro, Kati Horna, or Robert Capa—made possible the close-up and in-depth documentation of both the horrors and the boredom of war. New technology allowed photographs to be transmitted via phone and radio waves, permitting viewers far away to see images taken at the front just a few hours before. Photojournalism and improved printing technologies—Life magazine began in 1936—brought high-resolution images into the kitchens and living rooms of people all over the world. Pictures, for example, of kitchens and living rooms in Madrid or Barcelona sheared open by bombs, like so many hinged doll houses. Smaller and better movie cameras made impactful newsreels part of everyday culture. It was not uncommon for the captions of photos or the narrations of newsreels to focus as much on the technological marvels that brought the images before the eyes of the spectators so quickly, as on the object of representation of the image itself.

For most of the war, direct travel to Spain was impossible or impractical. American volunteers like Abe Osheroff, Hy Katz, or Barton Carter who wanted to join the International Brigades in Spain had to go to France first. And because their reason for traveling—to participate in a foreign war— was illegal, they needed an alibi for boarding a Europe-bound ship in New York harbor. Some of them announced rather implausibly to border officials that they were off to see the World’s Fair in Paris, which ran from May to November of 1937. I doubt any volunteers actually realized their alibi and attended the Fair. They had more important things to do, like making it down to France’s southern border and walking across the Pyrenees into war-torn Spain. But had they made it to that Fair, they undoubtedly would have found their way to the Spanish pavilion that everyone was talking about, and within that pavilion, if they got there in July or later, they would have seen Picasso’s Guernica: one artist’s rendition of what impelled the volunteers to head to Spain in the first place: carnage, or in Abe Osheroff’s unwitting and prescient description of Picasso’s painting via newsreel footage: “civilians gettin’ plastered all over the place”.

The promise of technology to improve the quality of life had been a standard theme for World’s Fairs throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The 1937 International Exposition in Paris was no exception; the tagline of the Fair could very well serve as a fitting if sinister subtitle to Picasso’s massive painting. “Art and Technology in Modern Life”

***

In an old story, a Gestapo officer visits Picasso’s Paris studio in Nazi-occupied France. Poking around the place, he comes upon a large photographic replica of Guernica. The Nazi asks: “Did you do that?” Picasso replied: “No, you did.”

The tale is certainly apocryphal, but it’s a helpful vignette because it points us in the direction of the ambiguity of the term “Guernica.” Guernica is a small city in the Basque Country of great symbolic importance to the Basque people; it also denotes an event, since on April 26, 1937, in one of the first and most dramatic examples of aerial terrorism, planes from Hitler’s Condor Legion and Mussolini’s Aviazone Leggionaria, carpet-bombed and strafed the town on market day for more than three hours non-stop, when the streets were full of buyers, sellers, livestock, etc.; and Guernica, finally, is a work of art, for some THE work of modern art, that was commissioned, as we have seen, to be exhibited at the Spanish Pavilion at the International Exposition of Paris in 1937.

If “What is Guernica?” is a tricky question, so too is “Where is Guernica?” Of course we can trace the sinuous trajectory of the actual canvas with relative precision: from the 34 days it spent in Picasso’s Paris studio while he hastily painted it, to its subsequent summer and autumn months at the Paris Universal Exposition; later extensive touring around Europe before coming to the US for more touring; its eventual deposit at the MOMA, where it remained for decades, because the artist had stipulated that it should never be exhibited in Franco’s Spain. After Franco’s death and Spain’s transition to democracy, and after a lengthy and complicated set of negotiations, the canvas finally did come to Spain in 1981; was installed first at the Casón del Buen Retiro, right next to the Prado, until its apparent final resting place was prepared for it, in the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía.

But where is Guernica really? There’s no need to reproduce it here. Guernica—the image—is ubiquitous, and it pops up in the strangest of places—on the walls of dorm rooms, on jigsaw puzzles, on drinking-glass coasters, etc. Moreover, the era of carnage that the painting depicts and ushers in is tragically still familiar. The news might be about Ukraine or Gaza: Guernica is still an apt illustration.

A couple of years ago, less than a mile away from the Reina Sofía, where Picasso’s Guernica is enshrined with all the sanctimonious aura of Modern Art here in Madrid, I went with a friend to see one of the strangest things one could ever imagine: a museum show of the work of Banksy, the elusive street-artist. On the way to the Círculo de Bellas Artes, we wondered how in the world Banksy’s work would be curated in the context of a museum, how some of the most site-specific images ever produced since Altamira would be treated in what was being touted as a blockbuster international traveling show.

The show itself was absurd, and as we walked through its many rooms, my friend and I looked around for cameras that might be filming the spectators who were perhaps unwittingly participating in a massive Banksy reality hoax. The work was framed and illuminated and presented more or less as if it had been created for, and belonged in, a conventional art museum. And we all paraded dutifully through room after room, spending more time looking at the labels than at the works themselves and trying to come up with clever things to say about these impossibly out-of-place objects.

But by far the most bizarre element of the show for me, and the element that got us thinking and talking about Guernica, was the video installation that visitors were obliged to watch, seated, before being able to walk through the galleries. On a multi-screen wrap-around display, in a dizzying sequence of zooming-in satellite photographs, the original locations of Banksy’s street art were pinpointed one after the other, as if they were the targets of smart bombs. Neighborhoods were presented as if seen from the nose-cone of a bomb. The textures and idiosyncrasies of those neighborhoods which, in theory, give meaning and context to Banksy’s site-specific interventions, were reduced to a set of GPS coordinates. Right then and there, I was reminded of our introduction to this kind of technology and this kind of footage. It was during the Iraq invasion of 2003, when the nightly news treated us day after day after day to footage supplied by the Pentagon. Point-of-view shots of bombs homing in on their targets, doing their civilizing job of shocking and awing, supposedly with surgical precision, with nary a bloodied child, woman, horse, or bull anywhere to be seen.

On February 5, 2003, Secretary of State Colin Powell and Ambassador John Negroponte gave press conferences at the entrance to the Security Council room at the headquarters of the United Nations in New York. Armed with satellite photographs of what were allegedly weapon factories in Iraq, Powell and Negroponte stood before a huge blue curtain, and made their case for the impending and necessary invasion of Iraq. Reporters and diplomats familiar with the space chosen for this momentous press conference noticed something amiss: that blue curtain backdrop had been placed there to cover something up: the full-size tapestry of Picasso’s Guernica that had adorned that space since 1985. When the news broke of this unusual cover-up of the Guernica tapestry, and ever since, all kinds of accusations and hypotheses have been thrown around to explain the change in décor for that press conference. But I’m pretty sure my friend and I might have come upon the definitive explanation as we exited the gift shop through the Banksy exhibition.

***

When does something, anything, actually begin? When does something, anything, actually end?

In some ways, the torn and tattered, well-traveled version of Guernica put forth in this painting is an extraordinarily fitting and provocative emplacement of Picasso’s work, maybe even more so, I dare say, than the august room that the original painting now presides over in the Reina Sofía. Obviously, a massive canvas by Pablo Picasso is not as out of place in a museum setting as a stencil and spray paint intervention by Banksy. And yet, the process of plucking Picasso’s work from the black-and-white mediascape out of which it emerged, from the propagandistic urgency that animated it in the first place, is also a form of displacement and violence, and, paradoxically, a way of forgetting through commemoration. Frames are to art what the brackets that envelop beginning and end dates are to the flow of history, to the flow of life. Helpful and necessary? Maybe. Distorting and decontextualizing: for sure.

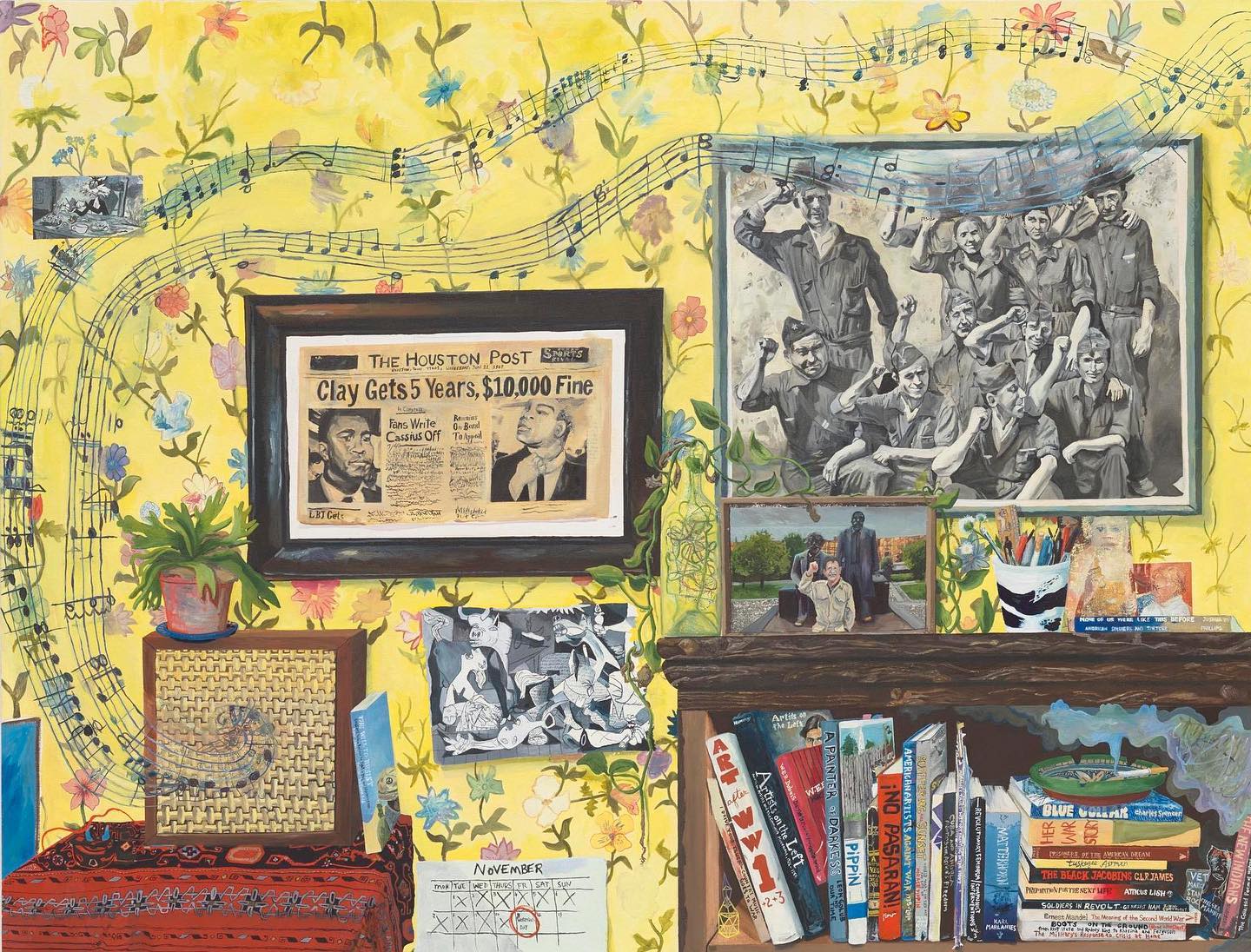

This painting was done by Celeste Dupuy-Spencer in 2016. It is in the Whitney Collection, and it is titled Veterans Day. A makeshift calendar points to the importance of that day of commemoration—someone has been crossing out the days leading up to the present depicted in the painting, which is circled in red—Veterans Day, 2016. And yet, in the entire gallery of characters that the painting references and recreates, there is not a single officially recognized veteran to be found. A newspaper clipping memorializes Cassius Clay—later Mohammed Ali’s —momentous decision, at the peak of his boxing career, to declare himself a conscientious objector and refuse to serve in the VietNam war. “I ain’t got no quarrel with the Viet Cong.” A draft dodger being celebrated by someone who is keen on commemorating Veterans Day. A large framed photograph represents a group of Abraham Lincoln Brigade volunteers, giving the popular front salute; these brave men and women, who, as we have seen, stood up to fascism five years before Pearl Harbour, have never been granted the official status of veterans; in fact, they were written out of most versions of the history of “The Greatest Generation.”

So: how are we to make sense of Dupuy-Spencer’s Veterans Day commemoration of non-veterans, or some might even say of anti-veterans? The painter herself gives us a number of clues. A book on the top shelf of the bookcase is titled “Art After World War I +2 +3”, playfully suggesting that history is an open-ended and ongoing sequence of wars. The visual representation of the music that swirls out of the record player speaker also has a kind of open-ended energy to it, as the music would seem to spiral out and across the threshold of the painting’s frame and resound into the future. And then, of course, there is the Guernica.

Dupuy-Spencer’s painting begins to make sense only if we recognize that the vision of history that it comes out of and that it puts forth is one that eschews conventional frames, standard distinctions, beginning and end dates carved in stone. Her veterans are not the survivors of wars that have been packaged and named and dated by nation-states or ideological blocks; her veterans are survivors, as it were, of The Good Fight.

Her painting helps us realize, in fact, that once cleared of all the nationalist borders, frames, and periodizations that they forced us to learn in school, history, as Peter Carroll has been saying for years, can look entirely different to us. And we can start to trace clear through lines that run, for example, from the terrorist bombing of Guernica, through Hiroshima, Operation Shock and Awe, and on to the disgraceful drone warfare that we now tolerate or accept without flinching. That blue curtain in the United Nations was an attempt to block that through line, that association, between the carnage from the sky in Guernica, and the carnage from the sky about to be unleashed in Bagdad.

Dupuy Spencer’s painting, finally, can help us reclaim Barton Carter, Hy Katz, Abe Osheroff and Cassius Clay/Mohammad Ali as admirable veterans, in an ongoing war. Abe Osheroff perfectly sums up this war: “You resist. Win or lose, you resist.” This was and is a war that begins anew every day; it’s a war that pits those who insist on looking at human suffering and injustice with the distance and indifference of a satellite or a drone, who insist on looking at the victims of aerial bombardments as inevitable “collateral damage,” against those who, like Picasso and Dupuy, embrace the on-the-ground perspective of solidarity and empathy towards all of those civilians getting plastered all over the place, through no fault of their own. Nation-states may declare the beginnings and ends of wars, the winners and the losers: but if we eschew the idea that nation-states are the only proper agents, protagonists and framers of history, we can see that the struggle for decency and dignity, for justice and freedom, knows no borders, no clear-cut beginnings and endings. This, the Lincolns knew.

James D. Fernández is Professor of Spanish at NYU, director of NYU Madrid, and a longtime contributor to The Volunteer.