Karen Nussbaum: “Good Organizing Means That You Don’t Tell People They’re Wrong.”

Earlier this year, we received an unexpected email from Karen Nussbaum, the legendary labor activist, asking to be put on the mailing list for the Volunteer. She explained that she’d read the magazine during a visit to her father, the actor Mike Nussbaum, a longtime ALBA supporter. One thing led to the other, and in November, Ms. Nussbaum was featured in the Susman lecture, as part a year-long programming series on labor.

In early 1970, when Karen Nussbaum was a sophomore at the University of Chicago—after a first year in which she spent less time in the classroom than protesting the Vietnam war—she decided to drop out to travel to Cuba with the Venceremos Brigade.

Soon after, she found herself in Boston, working at an office at Harvard and organizing against the war and for women’s rights. While picketing for eight striking waitresses from a Harvard Square restaurant, she was struck by the gap separating the women’s movement from the labor movement, and decided she wanted to bridge it. In 1972, with ten friends, she began issuing a newsletter called 9to5, addressed to women office workers. The following year, they launched an organization by the same name, which would eventually become 9to5: National Association of Women Office Workers and spawn SEIU’s District 925, which successfully held union drives for women workers across the country—a story told in a recent documentary by Julia Reichert and Steve Bognar. In 1980, their work inspired the hit movie 9 to 5, with Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin, and Dolly Parton.

In the 1990s, Nussbaum served as director of the Women’s Bureau in the Department of Labor and the AFL-CIO’s Working Women’s Department. She went on to found Working America, the community affiliate of the AFL-CIO, where she is a senior advisor today. Born and raised in Chicago, she lives in Washington D.C. In November, she was featured in ALBA’s annual Susman Lecture.

Did you grow up in a politicized household?

Not really. My parents were New Deal Democrats. My mother was a precinct woman for the Democratic Party in our district and my father was an observer of the world around him. But my sister, my brother and I did grow up with a clear idea of what it meant to be a good person. Reading was also highly valued, because it allowed one to see oneself as part of a larger world. In the late 1960s, as that world began exploding around us, we were able to apply those principles. At that point, my parents also became more active. We’d go every Saturday for a silent vigil in front of our public library against the Vietnam war. And when my mother invited Staughton Lynd to speak about the war at our community recreation center, we got hate mail from the Minutemen, the right-wing organization, with rifle crosshairs on it. As a teenager I didn’t understand that this could be dangerous—and I didn’t realize till later how brave my mother had been.

You went to college in 1968. Quite the year to do that.

There was no better time to become an adult. It was like the world was blowing up and you could do anything you wanted to try to change it.

So much so that you dropped out.

Politics was just so much more interesting! I February 1970, I ended up going to Cuba on the second Venceremos Brigade, which had been founded by the SDS in 1969. There were some 700 of us, including several people from the Weathermen. Although the whole thing was a bit of a mess, it was also very exciting to be part of a totally internationalist environment. When I got back, I realized I wanted to use what I’d been learning in the civil rights movement, the antiwar movement and the women’s movement in the context of labor. But because in those days we rejected old structures, of whatever kind, we decided to build our own. And we quickly realized that the most important thing we could be doing was to organize people across lines of difference.

Do you mean class and race?

Exactly. We wanted to organize women, for whom there were very few job opportunities. But we weren’t interested in the traditional feminist movement. We wanted to build out our own brand of feminism among working women. At that time, many women across class and race were doing the same kinds of jobs. One third of working women were clerical workers. And because these women found themselves in the same workplaces, that created a potential for solidarity across class and race that normally is very hard to find or build. We thought we should take advantage of that.

Tell me about your tactics.

We used to say: “Don’t let your words be the enemy of your ideas.” Since the women’s movement was primarily made up of middle-class white women, we left behind their rhetoric. We never used the word feminism. The women we were organizing would tell us: “I’m no women’s libber, but I believe I should get equal pay and fair promotions and be treated with respect”—all elements of the feminist agenda. We didn’t have to call it feminism to find common ground. And I think that principle is still important: It is not a good idea to impose a framework on people before they’re ready to adopt it.

That sounds like a critique of the current generation of activists…

I wouldn’t call it a critique. But I think that good organizing means that you don’t tell people they’re wrong at the outset.

Speaking of generational dynamics, how did you relate to the Old Left, which by then had suffered two decades of McCarthyism and Cold War tensions?

There was almost no continuity with the Old Left, either organizationally or at the leadership level. Looking back, I think that was a real weakness of my generation. Personally, I did connect with some older people who I thought knew what they were doing. At one point, I got in touch with a woman who’d been a Communist in her early days. At first, she didn’t want to talk to me about it at all. When I eventually drove across Connecticut to meet with her, she told me: “You have nothing to learn from us. What we did was all wrong.” But when I asked her about her day-to-day experience, details about daily structure came out. “We’d have mass meetings on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday,” she said, for example, “because your cell meetings were on Wednesdays.” Our conversation helped me understand what it was like to operate out of a party instead of these floppy, messy mass organizations that we were involved in, and that were often not even real mass organizations.

The Cold War broke that link of generational transmission among the Left.

It certainly did. It shows that repression works, as it did after World War I, when political repression took out a mass-based socialist movement in this country. The Cold War had that same kind of effect. It meant that we ended up with a movement in the 60s where there were different storms going on—whether it was civil rights or antiwar or feminism—but there were no good structures to hold them together. This meant that as soon as they abolished the draft, the antiwar movement collapsed. Feminism got bought off, too: When professional and managerial jobs opened up, we lost class solidarity among women. At that point, the focus of the civil rights struggle shifted from fairness to opportunity. This shift took the class element out of the struggle.

Just as the 9to5 movement has a foot in the door, Ronald Reagan is elected and the labor movement goes into a long period of austerity and retrenchment. These past couple of years, though, the tide seems to be turning back to labor. Do you agree?

Public opinion has shifted but I don’t know if the structural barriers to labor power will be overcome in this period. A few years ago, I read Vivian Gornick’s The Romance of American Communism, a series of interviews with Communists from the 1940s and ‘50s. Some of the people interviewed are critical, some are angry, and some thought it was a good experience, but they all agreed on one thing: what was thrilling about the movement was that there was both vision and discipline. What we have now, I feel, is a lot of strategy and tactics, but not so much vision and discipline. You need all those things. And you need to have a class-based framework for what you’re doing. Without it, it’s too easy to divide people. We don’t call it the ruling class for nothing. They rule, and they’re going to do so in the interests of profits. You need movement and passion—but you also need organization and democratic control. Without them, you may make changes in policy, but you won’t achieve any long-lasting changes in power.

Has that been a structural challenge for the Left in this country?

Yes. Michael Kazin has a great book about that, American Dreamers. We may make social and cultural gains, but these don’t fundamentally alter the balance of power. How do you organize for power for the long run? That is the real question that political activists need to consider. The answer, of course, may take different forms depending on the moment. Today, a priority is a united front against fascism, just like we did a hundred years ago.

You’ve spent your entire professional life building and working in organizations, from 9to5 and the SEIU to the Clinton administration and the AFL-CIO. Organizations are instruments of change, but they are also slow and inert, weighed down by their internal cultures and entrenched ideologies. When you came up, for example, the labor movement itself was deeply sexist. How do you do deal with the frustrations associated with that?

I don’t take it personally. Look, I believe in the power of organization, but as you say, they can be messed up. But if you choose to change an organization from within, if you take things personally you won’t last a minute. And that’s especially true for my generation of women coming up in the labor movement. My goal was to make change for working women, and I thought the labor movement was the place to do it, as one of the three mass-based institutions along with churches and political parties.

Still, even in the labor movement, making change is hard work with no shortage of setbacks.

Of course. Because of the internal dynamics you’ve mentioned and because any movement or an organization is always subject to outside forces, like neoliberalism and the massive onslaught of union busting we saw in the 1980s and ‘90s. When the sky falls, you stick it out, and then you emerge to survey the damage. It’s also important to realize that the US labor movement has the worst structure and labor code of any labor movement in the developed world. It’s designed for inertia.

How do you deal with those challenges?

You just keep chipping away, and you keep looking for historic moments that can open things up.

In other words, be pragmatic and realistic.

Every victory generates a backlash, which hollows a movement out from the inside. Just look what Phyllis Schlafley did to women’s rights in this country. You can’t be naïve. You have to anticipate the backlash. I mean, one third of this country is solidly right wing. That’s been true at least since the 1930s. When we associate the ‘30s with the New Deal, we forget how big and powerful the fascist movement was here. The trick is to make social and cultural change, and make it feel permanent, while making sure you’re prepared for the response. And on the positive side, be prepared for opportunities to make a leap forward.

Which brings us back to the importance of organization.

Exactly. That’s where the challenge is today. Over the years, I’d pose the same question to the women I’d meet: “Who do you turn to when you’ve got a problem on the job?” At the very beginning, in the ‘70s, women might say: “Well, I might call my Congressperson, or maybe I’ll call the Equal Opportunity Commission or 9to5.” But then as time went on, people might say: “Well, I might talk to a coworker.” Then it became: “Well, I might talk to my mother.” The avenues became narrower and narrower—until by the 2000s, people said: “Well, I might pray to God.” Collective solutions, in other words, have steadily narrowed or disappeared. And rebuilding those is a very big job. Women have become more self-sufficient individually since the 1970s and less powerful as a group.

Are you hopeful?

That’s irrelevant. I’m a very positive person, and you gotta do what you gotta do. I have a five-year-old granddaughter who was practicing her letters with her mother recently. My daughter asked her child what she wanted to write. What she wrote was: Grandma fell in a pothole. This was true: six months earlier, I had told her that I’d been riding my bicycle, I fell in a pothole, and broke my finger. When my daughter told me the story, I thought that could be my epitaph. I’m on my bicycle, I’m pedaling along—and then boom, neoliberalism happens. But I get back on my bicycle and I’m pedaling along—and then boom, 9/11 happens, and everything shuts down. Yet I get back on my bicycle because I feel that’s our obligation. In the end, we are lucky to be able to live our lives with purpose.

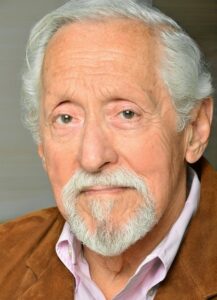

Mike Nussbaum, who turns 100 in December, is a well-known stage, television, and movie actor and director who has appeared in films ranging from Field of Dreams to Fatal Attraction. Based in his native Chicago, he is also the father of Karen Nussbaum—and a longtime subscriber to the Volunteer.

Mike Nussbaum, who turns 100 in December, is a well-known stage, television, and movie actor and director who has appeared in films ranging from Field of Dreams to Fatal Attraction. Based in his native Chicago, he is also the father of Karen Nussbaum—and a longtime subscriber to the Volunteer.

Do you remember when you first heard about the Spanish Civil War?

I was a freshman in high school. At the time, I thought of myself as a socialist or communist. This meant I was very much involved in the war on a mental and emotional level.

Did you go to mass meetings?

Not that I remember. It would have been hard for me to do so because my parents weren’t interested in any form, and I couldn’t travel on my own.

I understand that as a young man you served in World War II.

Yes. But when I joined the US army and told them my history, including the fact that I’d favored the Republic in the Spanish Civil War, they called me a premature antifascist.

Who did?

The sergeant who interviewed me. I figured that they would keep me far away from any secret work.

Did they?

No, to the contrary! I wound up working in the supreme headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force as a sergeant sending classified messages. That’s how well they watched their secrets, I guess. (Laughs.)

I read that it was you who cabled the news of the Germans’ signing the capitulation in Paris in 1945.

I did. I signed it Eisenhower and then, instead of just adding my operator’s initials in the lower lefthand corner, I signed my name, too.

In the postwar years, do you remember meeting any veterans of the war in Spain?

No. But I’ve always honored them. Those men and women gave so much to be in that war. I still have a sense of awe about those people who volunteered for that war and enormous respect.