UC Berkeley Approves Monument to Merriman and the Lincoln Brigade

Claude Potts & Donna Southard: “It Is Crucial to Tie the Lincolns’ Fight Against Fascism to World War II.”

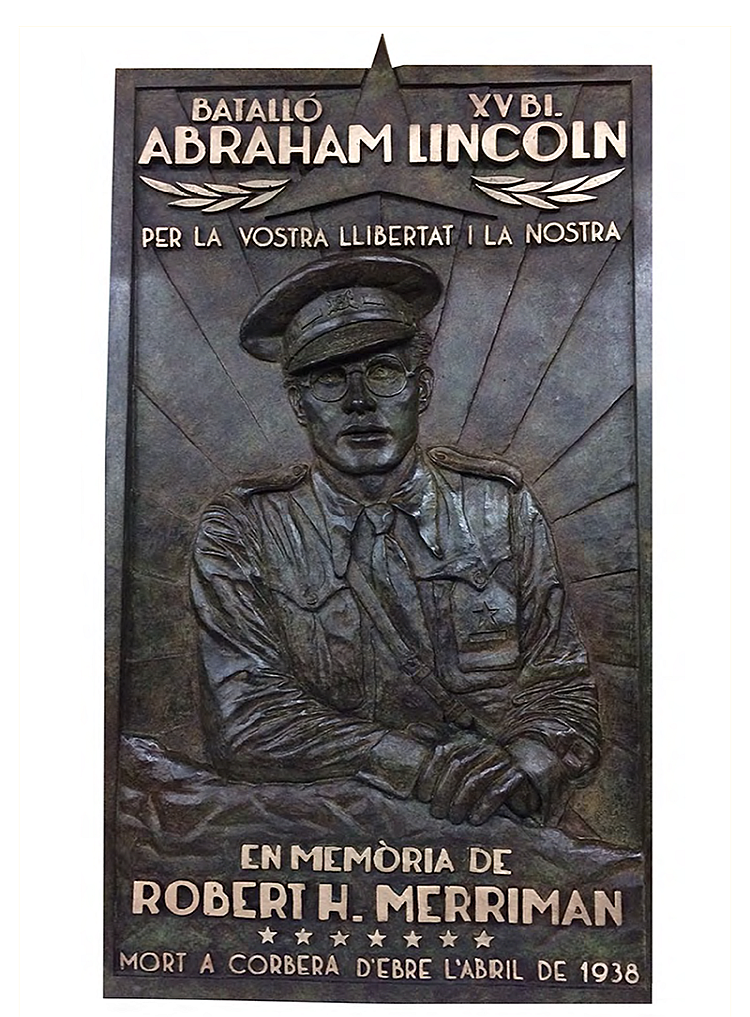

Since April 2018, the Catalan town Corbera d’Ebre has featured a bronze plaque in memory of Robert Hale Merriman, commander of the Lincoln Battalion, who went missing in action nearby in April 1938. A copy of the plaque will be featured in a new monument on the UC Berkeley campus.

The initiative for the plaque in Corbera, which was designed by the sculptor Mar Pongiluppi, came from a research group at the University of Barcelona that focuses on history education (DIDPATRI). Soon after, the group donated a second casting of the plaque to the University of California at Berkeley, where Merriman had been pursuing his PhD in Economics. Recently, the UCB administration approved the installation of a monument featuring the plaque embedded in a large boulder and placed at the center of campus near Memorial Glade, which honors Berkeley veterans of World War II, along with a smaller informational plaque in English about the US volunteers in Spain. The two people who have made this happen are Claude Potts, the UCB librarian for Romance Language collections, and Donna Southard, who teaches in UCB’s department of Spanish and Portuguese. I spoke with them in October.

How aware is UC Berkeley of the impact the Spanish Civil War had on its campus?

Donna Southard (DS): There was a lot happening on campus in 2016 to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Spanish Civil War. Claude, Theresa Salazar (curator of the Western Americana collection in Bancroft) and I, for example, organized two very visible library exhibitions, and Peter Glazer performed his musical Heart of Spain.

Claude Potts (CP): There were also coordinated book talks, readings, lecturers, and film screenings. One of the most memorable events were the book talks Adam Hochschild—a journalist, historian, and lecturer in the Graduate School of Journalism—gave on his award-winning book Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 which centered on Bob and Marion Merriman. So, there was some awareness of the Spanish Civil War when the initial offer of the plaque was received. We, of course, made an effort to connect those events to our proposal.

How did the administration respond?

CP: It’s important to note that the plaque was offered to Chancellor Christ herself first and that she felt supportive enough to contact The Bancroft Library, where a collection of materials related to the Abraham Lincoln Brigade resides, for ideas on where to install the plaque. The offer got lost in the shuffle of the Coronavirus pandemic and Donna and I can take credit for bringing it back to everyone’s attention.

DS: After threading its way through the complex year and a half-long approval process, our proposal for an outdoor art installation was finally approved by the Chancellor’s office last semester. The committee that reviewed it was sensitive to the implications of another straight white male being honored and wanted to make sure that we would emphasize the diversity of the volunteers and the internationalist effort they stood for in the fight against fascism.

Speaking of internationalism, has there been any political pushback?

CP: We’ve always been concerned that there might be, but it hasn’t really come up.

DS: The bigger concern—I wouldn’t call it pushback—was about providing more racial and gender balance in the representation of mostly historical figures connected to the campus in some way. If pushback of a political nature comes up at any point, our response will be that the university is precisely the place to go beyond reductionist interpretations of the complex political dynamics that led to the Spanish Civil War.

Is it significant to you that this monument will end up in close geographic proximity to the national ALB monument in San Francisco?

DS: Absolutely. It ties the UC Berkeley campus more closely to the Bay Area Post of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. There are at least eight other Berkeley students who fought in Spain that we know of. So, this monument not only brings them into the discussion, but it also highlights the importance of their educational experience at Berkeley with regard to their personal evolution, which ultimately led to risking their own lives fighting against fascism, even when their own country chose the path of non-intervention.

CP: Another link that we envision with the larger monument in San Francisco is that it makes a symbolic bridge between ALB volunteers throughout the Bay Area who came from different walks of life yet were united for the same cause. Merriman, who grew up in the Santa Cruz mountains and came from a working-class family, joined the frontlines of the 1934 West Coast Longshoremen’s Strike by volunteering in its publicity office. When Cal’s football coach recruited his players to go to the docks to support the shipping companies against the strikers, Merriman responded by organizing a crew of Berkeley students and encouraged them to support the strikers, who were mostly whites, blacks, Chinese, and Filipino Americans.

How do you view the balance between the focus on Merriman—who was photogenic, charismatic, and met a mysterious death—and the need to acknowledge the broader group of volunteers from Cal and the rest of the US?

DS: Merriman was not only photogenic and charismatic; he was also one of the few American volunteers with any military training, so he became a leader. He was also tall. This physical presence made him a memorable figure to the locals, who called him el americano alto. So, when the University of Barcelona’s DIDPATRI research group conducted their interviews in the small town of Corbera, the focus naturally fell on him. But part of our purpose of installing this monument on campus is precisely to call attention to the broader group of volunteers, which will be acknowledged explicitly in the secondary informational plaque. We feel it is crucial to tie their fight against fascism during the Spanish Civil War into the more familiar conflict of World War II. This is why it will be installed at the center of campus near Memorial Glade, which honors UCB’s veterans of the Second World War.

CP: Besides the challenge of not having a lot of information about the other volunteers from Berkeley, we also think that there is a role in heroifying individuals with physical monuments like these and Merriman is certainly a hero who has not been properly honored in this country.

What do you hope the monument’s presence on campus will inspire, in the classroom and outside of it?

DS: Biography is a great way into history. The presence of the Merriman plaque on campus, its physicality, will stimulate interest in his biography and, from there, discussions of the Spanish Civil War that go beyond Merriman himself and beyond the Spanish Civil War itself to delve into the fraught period of socio-political complexities of early 20th century Europe that have to do with the unevenness of modernity, which many thought were behind us.

CP: Since the words on the plaque are in Catalan, we imagine visitors are going to wonder what this is all about. The significance won’t be as obvious as the statue of Mark Twain in the library, the bust of Abraham Lincoln on the iconic Campanile, or the various sculptures of grizzly bears, extinct in California since the 1920s. The secondary plaque we are installing on the same stone will allow people to learn more about Merriman. We would like this plaque from Spain, along with the historical marker placed by the city in 2019 on the apartment building just north of campus where Bob and Marion Merriman lived —as well as the monument in San Francisco—to be destinations for school field trips and tours of all levels.

Has your work on this project changed your own view of Merriman, the volunteers, or the Spanish Civil War?

CP: I first learned about Merriman through Hochschild’s book in 2016 as I presume many people did. I remember it received a lot of critical acclaim and was featured on NPR. Since then, I’ve read a lot more and have grown to appreciate Merriman’s intellectual motivations even more. Just last week, I came across a few articles in The Bancroft Library that he wrote while on a fellowship in Moscow for the leftist journal Pacific Weekly published in Carmel. Like so many ALB volunteers, he was an extraordinary human being who was committed to making the world a better place. It doesn’t stop with Merriman. I’m equally interested in learning more about other local volunteers such as his wife Marion Merriman Wachtel, née Stone, who was a hero in her own right. She was the only woman to serve in the ALB and served as commander of the Bay Area Post of VALB for several decades. I’m interested in reading more about Archie Brown, Milt Wolff, Alvah Bessie, Bill Lawrence, and Oliver Law, the first African American to lead an integrated military force in the history of the United States. At the moment, though, I’m keen on digging deeper into the lives of lesser-known Berkeley students who went to Spain such as Mark Billings, Dick Cloke, Cecil Cole, Ramen Durem, Wade Rollins, Gerry Quiggle, Clifton Amsbury, and Don McLeod.

DS: I was not aware of Merriman before joining this initiative, but I lived in Spain from 1975-1998, and then focused primarily on early twentieth century Spain for my doctoral studies as a reentry student at UCB. So I was very aware of the role the volunteers played in the conflict. What has always made an impression on me is how revered the IB volunteers are to this day in Spain—and how forgotten they are in the US. This project has connected me with ALBA and the members of the DIDPATRI group, who took me to visit the ruins of the town where Merriman died. Since I am especially interested in memory work, I’m heartened that both groups are so committed to it. In Spain, this is less surprising. After all, the war was fought there, so there is a great deal of social awareness and institutional support. This is obviously much less the case in the US. ALBA’s incredible heart and perseverance has really had an impact on me. I’ve constantly been inspired by what I learned working on the 2016 exhibitions mentioned earlier, by what I continue to learn working on this project and most of all by the deep humanity of the people I meet involved in some way with the volunteers.

Sebastiaan Faber chairs the ALBA Board and teaches at Oberlin. For more information about the Merriman monument, see here.