Book Review: Sketches from Spain

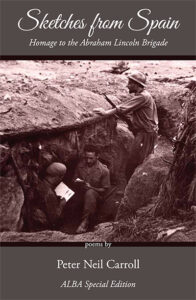

Peter N. Carroll, Sketches from Spain: Homage to the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, Charlotte, NC: Main Street Rag, 2024. ALBA Special Edition. 100 pp.

Peter N. Carroll, Sketches from Spain: Homage to the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, Charlotte, NC: Main Street Rag, 2024. ALBA Special Edition. 100 pp.

In this powerful collection, poet and historian Peter Carroll crafts portraits of some eighty men and women who volunteered to fight in Spain. Carroll observes, “Valuable as the work of historians and archivists is, I think poetry takes the task of understanding and empathy one step further.” He preserves the voices of veterans, in shaped utterances that convey an experience of speaking with unforgettable interlocutors. An opening poem, “Abe & Jack, Milt, Moe, Dave,” shows his relationship to them:

They were not my family. They distrusted

strangers. I could only approach them slowly …

[…]

They lost, bad guys won—they bore failure

like primal sin or first love that comes and

goes, never leaves. […]

Their example led me […]

to seek a role, a small role, or merely

the hope of a role—to speak against injustice.

Six sections organize this testimony. “Choices,” “War,” “Saving Lives,” “Artists & Writers,” and “The Long View” are self-evident: the clear or painful decision to join; medical as well as military participation; and adjustment to life in an aftermath of far-from-defeated fascism. Perhaps unfamiliar is the sixth subheading, the notably bizarre term “Premature Anti-Fascists,” a HUAC-era accusation leveled against returning Brigade volunteers. (To Joe McCarthyites, only after the U.S. entered World War II was opposition to fascism deemed to have been patriotic; having served earlier, in Spain, smacked of Communism.)

A place name can take on the echo of a resounding, usually horrific, event, as in “the anniversary of Hiroshima.” “Spain” functions in this collection as that kind of allusive code. For James Walker Benét (1914-2012):

He went to Spain, drove trucks

into battle, returned without a scratch,

wrote for magazines, newspapers, TV.

We weren’t heroes; they are buried

in Spain, we wonder if people understand

what we did and why…We hate war

but value freedom and democracy.

In deft triplets (3-line stanzas), another compelling account describes Chick Chakin (1904-1938), as known by a woman who loved him:

He had a trick knee. Otherwise,

he was built like an ox, an Olympic-

class wrestler, a collegiate coach.

He was going to Spain. She was scared,

she knew all about his knee. She’d seen

him half-squat, pull the joint into place.

He passed the medical exam. He was going

to Spain. The doctors found nothing wrong.

She wondered if they’d looked at his knee.

He could lose his life or someone else’s.

She wanted to tell, but she had her pride.

He had his pride—he was going to Spain.

Concision and inevitability foretell the ending—just as she knew. This apparently flat plain-spokenness gains power in the lines, by interweaving sound-repetitions or near-rhymes across stanzas (ox / coach / squat; Spain / scared / place. The direct repetition, “he was going to Spain,” sounds a knell toward the dread foreseen, as in great tragedies:

Without him, years later, she says, we all die,

some die young. He died for a good cause.

Spain—he went to Spain. He had his pride.

Dramatic rather than lyric, scenes and vignettes are full of such ironies: risking all and perhaps losing, or not risking and forever regretting. Or, gaining possible freedom—as for Eluard Luchell McDaniels (1912-1985) a bold, frankly unreliable, memorable narrator:

A Mississippi Black youth had scant

chance in Depression times, hopped

on a freight, rode west on the blinds.

He loved to tell stories, knew not

to spoil one sticking to the facts,

seldom did he need to do that.

Again, off-rhymes (Black / scant / chance / facts / that) catch the ear and set up a subliminal signaling. These are significant words, given the scant chance that life would offer a Black youth unable to navigate beyond facts when necessary:

When fascists rebelled in Spain, he went

to war, stopped in Paris to beg the exotic

Josephine Baker for a gift. She paid.

The fascists, he said, were the same people

they’d been fighting all his life. I hope you

get your black ass shot off, he said she said.

He did catch a flesh wound in Spain. I’ve

seen lynching and starvation, he said, I’d

rather die here than be slaved anymore.

McDaniels’s damning summary of life in America, and vision of changes to be won, echoes other Black veterans like Canute Frankson (1890-1941):

[… ] if we crush Fascism here

we’ll save our people in America. . .

[…] There will be no color line,

no jim-crow trains, no lynching.

That is why, my dear, I’m here in Spain.

In the same way that James Walker Benét insisted, “We weren’t heroes,” other speakers repeatedly reject special praise. It had to be done; injustice must be fought. Volunteers in Ukraine today—serving meals, or militarily—sound the same refrain, about stepping up to aid in a war that is both a humanitarian crisis and a resistance to looming international fascism. For onlookers aware of history, this puts the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, as Carroll’s preface points out, “back in the news.”

Amanda Powell is an acclaimed translator and senior instructor in the University of Oregon’s Department of Romance Languages. She is also a widely published poet.