Connecting the Dots, Creating a Tapestry: A Multigenerational History of Trauma

All families have secrets, and I discovered mine at a young age, in a box or paper bag, I don’t remember which, in the closet. I knew even then it was a secret, an important secret because no one in my family wanted to talk about my prescient treasure: letters and photographs. I was too young to read the letters and did not know who were in the pictures. I was confused and felt hurt or ashamed that I had done something wrong because my mother and father were upset and told me to put them away and refused to talk about my newly found objects, and I never could get them to talk about them till the day they died. I figured my parents must have a doozy of a secret that they carried to their graves. Little did I realize that this interest in secrets would lead to researching the mysteries of my family, becoming a family psychologist, and studying the legacies of generational trauma. Decades passed before I discovered another secret: there were many families whose a loved one who volunteered to fight in Spain, and they did not discuss it either, it was a secret.

The mystery starts to unfold with a copy of a letter, handwritten, dated March 8, 1937 (Entin, B.), which arrived, by email, in my inbox, February 7, 2023, a warm winter day. The contents, a mystery with demands. Written to a woman named Ruth, in an urgent, pleading tone, “the situation at present in the 5 & 10, (Woolworth’s) is ‘hot’ … the union is starting an intensive campaign to organize all the 5 & 10(s).” It is forceful and direct, get the girls of the Brooklyn group of workers to come to a meeting that Friday night. It was signed Butch, and underscored with four descending lines, reinforcing the urgency of the situation. As I read and reread the letter, I realized that I also have a copy of that same letter in my files. And then, I had a glorious “aha” moment, not only did I have the letter, but I had information about the event being planned, the Woolworth strike.

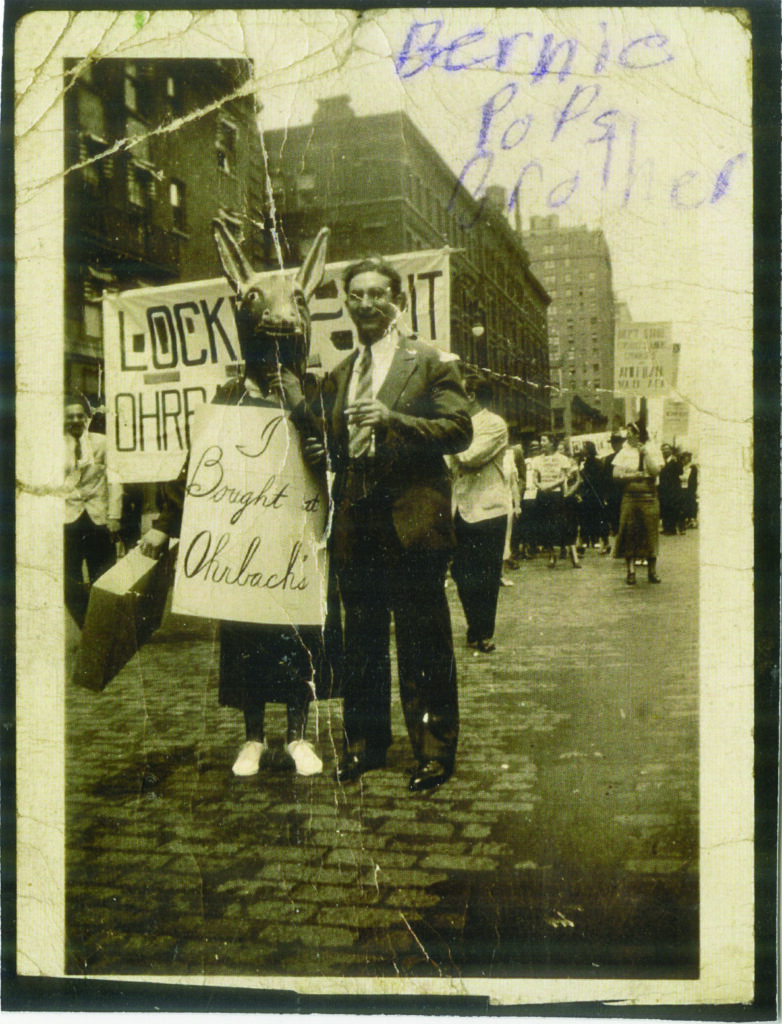

I was to learn that the pictures were taken at union strikes of department stores in New York. I thought the most interesting, and scary, picture was of a group of people standing around a person wearing an animal mask who was holding a sign saying “I bought at Orbach’s.” The curly haired man in a suit with a striped tie, standing next to the animal-like creature was Bernard, sometimes shorted to Bernie, and sometimes by the nickname “Butch.” Sometime later I printed his name on the picture with a colored pencil or crayon so that I would not forget it. The letters were, I learned, those Bernie wrote to his mother and my family about his feelings about them, and his thoughts about going to Spain to fight fascism in “not a civil war, but an international war” (Entin, B., July 15,1937): these were the letters and photographs I had so preciously saved.

The time frame of these events was the Great Depression of the 1930’s, Bernie had graduated high school, dropped out of college, was in his early 20’s, unemployed and joined the Young Communist League. Harry Fisher, who became best friends with Bernie, gave him the nickname “Butch.” They rode the rails, were arrested many times on picket lines and spent time in jail together. Fisher (1997) describes him as “one of the most militant members of the Department Store Union… a good-looking, husky, curly-haired guy who was tough as nails. Tough yes, but gentle and compassionate as well. He was someone you wanted on your side, and fortunately for us, we had him on ours”.

When I first received a copy of the letter, in the mid 2000’s, I had just started researching my family history and the Spanish Civil War and could not appreciate its contents or significance. Now, with almost 20 years of experience and knowledge researching both, I was able to connect the dots and complete a piece of the puzzle.

Gail Malmgreen, who worked as head of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives at Tamiment, New York University, had sent me a paper written by a student in one of her classes, which cited the Woolworth strikes in the New York Times (1937). In the Archives of the Times I found copies of the 1937 papers. March 16th the headline read “Fifth Store Joins Sit in Strike; Parley Today May End Deadlock,” and, two days later, “Woolworth Girls Strike in Two Stores.” What the letter Butch wrote to Ruth directly ties him to the event, the Woolworth strikes: the newspaper articles cite him as the organizer of the strikes. Bingo, I found the documentation of a link between Bernie, the union activist and the Woolworth strikes, which I never realized I had before. The receipt of the letter did not have any significance when I first received it because I had no knowledge of Bernie’s activities as a union activist nor about the strikes. Now, I was able to connected the dots in the tapestry of the legacy of an activist .

Thinking about those strikes being planned in the letter, I wondered if they were part of a larger nationwide initiative to organize workers and obtain benefits for laborers (Zinn, Frank, Kelly, 2001), especially Woolworth 5 & dime stores. I wondered if they sang as they protested. I wondered if they sang the song that we sing now, the Anthem of demand and protest for human rights, for justice and equality: “Will Overcome.” We are still protesting, but singing, “We Shall Overcome” (Caro, 2020, pp.165-166).

Butch sailed to Spain on April 21, 1937 aboard the Queen Mary and arrived in Cherbourg, France, April 26, and in May joined his friends from Brooklyn in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in Spain. He went to save the democratically elected government in Spain, fight Franco and fascism, and avoid a Second World War.

The first reference to Bernie I found when I started to research his story, online, was the Jewish Virtual Library (www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org), which referenced Jews in the Spanish Civil War (Sugarman) with a few basic facts, but I thought was pay dirt, since I did not think I would find anything from a war so long ago. My next search led me to found an article by Harry Fisher in a magazine of the organization of Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (2001). Reverting to old fashioned habits, I called. The vet I spoke with referred me to a book, Comrades, also by (Fisher, 1997), who wrote he was Bernie’s “best friend,” gave him the nickname Butch, and that as young men they rode the rails, spent many a night in jail, and had many adventures.

It was during the Battle of Brunete that Butch received a “blighty,” saw Fisher, and promised a quick return when the shoulder wound healed. This was not to be, however. According to a report from a first hand witness, “he was on his way to the first aid station down the road, or maybe to the ambulance waiting nearby” when it was hit by a Luftwaffe bomb” and it was “blown to bits and there was nothing left of him or the other wounded, according to an eyewitness” and Fisher wrote that he never again saw him (1997, 2001).

However, the evidence of Bernie’s death is scant, inconsistent and inconclusive. At the time, his friends had no knowledge about his whereabouts. A half of year later after the bloodiest battle of the war, his friends were writing to get information and express their anxieties. Irving Fajans, from his hospital bed, wrote the Commissariat of the International Brigades: “Butch was wounded about two weeks after I was, but I haven’t been able to get in touch with him. … (H)e was in the second company of the Washington Battalion” (Moscow Microfilm Archives, 1937); Fisher,

“There is nothing new about Butch. No news at all. Very Bad” (Letter January 23, 1938); and, Jack Shafran, “We have given up hope too – It’s five months now we haven’t heard from him – It’s a god-damn shame – But there is nothing can be done” (Letter, January, 1938).

In Prisoners of the Good Fight, Carl Geiser (1986) lists two references to Bernard: the Notes for Chapter 4, Captured at Brunete: “According to the 15th International Brigade records at the Institute of Marxism-Leninism in Moscow, the seven captured Americans who did not survive” included “Bernard, age 24, from Brooklyn p. 272).” However, it is inconsistent with other information, which lists eight “Americans Killed After Capture…At Brunete – July 1937,” Bernard, 22, (Appendix, Table 6-3, p. 263).” This, I have been told, probably means execution by a firing squad.

I am inclined to accept the information from Fisher about the death of Bernie since it contains a first person account. His birth, March 1,1915; his death, July 26, 1937; his age, 22 years, 4 months. He died three months after arriving in Spain on a cool spring day.

On sunny November day in 2010, a glorious rainbow was visible as our small group traveled to the Brunete battlefield. It was going to be a good day. As we entered the gate, I saw a spray painted rainbow -yellow, red and purple – colors symbolic of the Spanish Republic- a welcome sign. By the dried up Guadarrama River bed I planted a memorial, a Jewish star on wooden handle with the high school graduation photograph of Bernie. I recited the Kaddish, the ancient mourning prayer for the dead. Upon leaving, the sky was filled once again with a rainbow and me thinking Bernie might be smiling down, approvingly saying thank you.

I wondered if my parents’ reluctance to talk about him was because of their anxiety that what happened to Bernie would also happen to their family, a form of emotional heredity, repeating patterns of behavior over generations. I wondered what was it about Bernie they were so ashamed or fearful about to acknowledge. He was involved in a paternity suit, found not guilty, but in a second suit, with different standards of evidence, responsible for support. The lawyer’s bill was paid depleting the inheritance from his father’s recent death. He dropped out of college. He was in and out of jail as a hobo and labor activist. He became a member of the Young Communist League at a time supporting Communism was acceptable. In many families, it was discussed, however in many families

it was a secret. And going to Spain to fight fascism was seen as supporting Communism and experienced as “growing up scared” (Szermeta, M.), 2022), “created a battle at home” (Retish, 2022). In contrast, Daniel Millstone says “My parents didn’t tone anything down … Memories of Spain were omnipresent. I heard about it probably before I could talk” (Faber, S., 2023). In Bernie’s family there was “conflict and tension,” according to a cousin. He did not tell his family he was going to Spain to fight Franco and fascism. After his first letter from Spain arrived, his mother suffered a series of strokes. Any and all of these life circumstances may have culminated in their pact of secrecy. Insightfully, a psychologist friend, Michael Roberts, PhD, commented, “(A)fter a time of not speaking about a relative, when does one start talking about them?”(2023). And, there are some questions that can never be answered.

Our history, our identity, is shaped by those who are not in our family as much as those who are. When I started the research on my family there was only a 3X5 inch index card in the ALBA archives that listed Bernard’s name, address, and Brunete and KIA, which in my naiveté I did not understand, but which was quickly revealed: killed in action in the battle of Brunete (VALB, 1937). Now, according to Malmgreen there is a “venerable vertical file” about him at Tamiment. Yet, there are still lots of pieces of the tapestry of Bernie’s life and my family’s history that are missing and will probably never be known. In his death, as in his life, mystery and inconsistencies exist, questions cannot be answered. It is another step in connecting the dots and creating a tapestry in the family history, one, however that may always be incomplete and inconsistent, always a mystery. The secrets of my family are also their gift to me, my trauma legacy, what makes me today the psychologist that I am.

I help families unlock their family secrets, often through the use of photographs and family albums to understand family relationships.

The journey to discover my family history merged my professional and professional passions: I am a family psychologist and photographer, and I help families discover their secrets through their family photographs and albums, the icons of their families (Entin, 2021). And those who knew Bernie, personally or by reputation, knew him to be a “hero,” just as all those who volunteered to fight for the Republic against fascism were heroes. He was a strong dynamic personality, a leader clearly admired and remembered, even 80 years after his death. We can only wonder about how he would have lived his life, what he would have accomplished, and the impact he would have had on myself and the family, and his contributions to society had he not died so young. This was his legacy, to leave the world a better place, just one of the many important lessons I learned from him and which influence me to volunteer and “give back” to my community and my profession.

Harry and Ruth Fisher, married on April 13, 1939, named their son, born March 19, 1943, John Bernard Fisher, the middle name in honor of his “best friend,” Bernard,“Butch,” Entin, my uncle.

“Salud, Bernie.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Caro, R. A. (2020). Working, Vintage Books, A Division of Penguin Random House, LLC, New York, pp. 165-166.

Entin, B. (1937, March 8). Unpublished Letter to Ruth Goldstein, Collections of Alan Entin and Noah Lederman, Jack Shafran File, The Tamiment Library, Robert F Wagner Labor Archives, Elmer Bobst Library, York University Libraries, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY, 10012.

Entin, B. (1937, July 15). Unpublished Letter, Bernard Entin File,The Tamiment Library, Robert F Wagner Labor Archives, Elmer Bobst Library, York University Libraries, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY, 10012.T

Entin, A. D. (2006, March). Salud, Bernie, The Volunteer, Journal of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, Vol XXVIII, No.1, 7-9.

Entin, A. D. (2021). Family Gifts and the Artful Practitioner: A Journey of Personal, Professional and Artistic Growth, In Different Paths Towards Becoming a Psychoanalyst and Psychotherapist: Personal Passions, Subjective Experiences and Unusual Journeys, Rachman, A., and Kooden, H., Eds, Routledge Books, London and New York, 56 – 80.

Faber, S. (2023, March). Faces of ALBA: Daniel Millstone. The Volunteer, Newsletter of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, New York, NY, Vol. XL, No 1, 14-16.

Fajans, I. (1938, January 23) Moscow Microfilm Archives. The Tamiment Library, Robert F Wagner Labor Archives, Elmer Bobst Library, York University Libraries, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY, 10012.

Fisher, H. (1937). Letter, Harry Fisher Files, The Tamiment Library, Robert F Wagner Labor Archives, Elmer Bobst Library, York University Libraries, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY, 10012.

Fisher, H. (1997). Comrades, Tales of a Brigadista in the Spanish Civil War, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London, pp. 197.

Fisher, H. (2001). Germans and Americans Facing Each Other Again. The Volunteer, Journal of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, New York, N.Y., Vol. XXIII, No. 3, p. 16.

Geiser, C. (1986). Prisoners of the Good Fight. Lawrence Hill & CO, Westport, CT, pp. 298.

New York Times. (1937, March 16). Fifth Store Joins Sit-In Strike: Parley Today May End Deadlock. New York, NY, Front Page, 1 & 8.

New York Times. (1937, March 18). Woolworth Girls Strike In 2 Stores. New York: NY, Front Page,1 & 4.

Retish, A. (2022, September). Faces of ALBA: The Family of Oiva Halonen.The Volunteer, Newsletter of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, New York, NY, Vol. XXXIX, No. 3, 14 – 17.

Roberts, M. C. (2023, March 3). email communication,.

Rowe, J. (2005). From The Picket Line to the Front Line: The New York City Department Store Workers’ Union and the Fight for Spain, (Unpublished Paper), TheTamiment Library, Robert F Wagner Labor Archives, Elmer Bobst Library, New York University Libraries, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY, 10012.

Shafran, J. (2005, August 14). Personal Communication. The Jack Shafran Papers. The Tamiment Library, Robert F Wagner Labor Archives, Elmer Bobst Library, New York University Libraries, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY, 10012.

Sugarman, M., (2005, September 24). Jews in the Spanish Civil War (Part 2), Jewish Virtual Library, online Jewish encyclopedia, www.virtualjewishlibrary.com.

Szermeta, M., (2022, December). Growing Up Sacred: A Memoir. The Volunteer, Newsletter of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, New York, NY, Vol. XXXIX, No. 4, 17-18.

Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (VALB,1937). 3X5” Index Card, Information filled out and maintained by the Friends of the Brigade on the eve of going Spain.

Zinn, H, Frank, D, and Kelley, D.G. (2001). Three Strikes, Miners, Musicians, Salesgirls, and the Fighting Spirit of Labor’s Last Century. Beacon Press Boston, MA, 2001, pp. 174.

Presented at the Convention of the American Psychological Association, on August 3, 2023.