The Cup of Free Spain: A Republican Memory Restored

After a yearslong campaign in the face of official resistance, a working-class Spanish soccer club can finally claim the cup they rightfully won during the civil war.

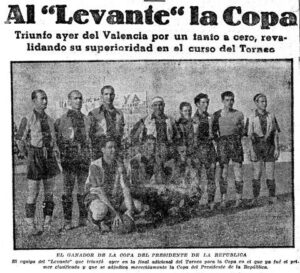

On March 25, 2023, La Copa de la España Libre, a soccer tournament played during the Spanish Civil War, was finally recognized by the Spanish Football Federation. It had been won in 1937 by Levante, a humble Valencian club born in the heart of El Cabanyal, a working-class port community historically outside of the city limits, made famous by artists like painter Joaquín Sorolla and novelist Vicente Blasco Ibáñez. Known for a stoic fan base and an amazing history of perseverance amid struggles, debts, and disappointing results, Levante finally has its first and only official title to its name.

Echoing the efforts of the memory movement in other areas, this recognition rewards decades of hard work on the part of dedicated club historians in the face of constant resistance from official agencies. (For comparison’s sake, the legitimacy of the 1939 Copa del Generalísimo, Franco’s first national soccer tournament, has never been called into question.) It’s a story of courage and honor, both on and off the pitch, that puts the spotlight on some exceptional heroes behind Spanish football’s longest-ignored trophy. It also showcases the way the Spanish Republic used sports to rally support, as well as the precarious circumstances of players who shared wartime responsibilities on the front with footballing duties on weekends.

In 1937, the Republican government, which had been moved from Madrid to Valencia the previous year, organized two football competitions to bring some normalcy to life during the war: a League (la Liga del Mediterráneo) and a Cup (la Copa de la España Libre), modeled after the national tournament that had been held before the war, the Copa de la República. It’s worth pointing out that the national Cup had a greater importance than today’s Copa del Rey: teams competed through regional groupings—with brutal local rivalries and bragging rights at stake—to gain access via the league table to a national tournament that culminated the season. (Today, all teams qualify into often anticlimactic national pairings and most bow out long before the season even reaches its midpoint.)

In that historic season of 1937, Levante’s side featured legendary players like Agustinet Dolz and Gaspar Rubio as they took on Valencia CF in the final, which was played in Barcelona. Both teams had qualified for the tournament via the Mediterranean League. Although today the Valencian Derby of Levante-Valencia may favor the latter, in those years, Levante was the stronger club, possessing more history, recognition, and regional titles. The game remained tied at zero for a long time, until the 78th minute, when Agustinet Dolz delivered the decisive cross to striker José García-Nieto Romero (Nieto for short), a 1-0 goal that sealed the score line. As it happened, both players were also famous Republican soldiers, whose efforts on the battlefield won renown to rival their legendary efforts on the football pitch.

Dolz, from El Cabanyal, was legendary for his assists. He left his impact on football slang in Spain: the phrase “Bombeja Agustinet”—roughly “Launch it, Agustinet” or “Bomb it, Agustinet”—is still used today. Known for having a glove for a foot, Dolz could perfectly place a cross for his teammates to score, his most famous one precisely being the one Nieto used to score that only goal in that 1937 Cup final. Dolz fought in the Battle of Teruel, coming back from the front on weekends to play for Levante. He was later imprisoned and held in a Franco concentration camp. When he finally returned to football, he would only play for Levante, spending the rest of his life connected to the club.

Nieto, the goal scorer, also saw time at the front, serving the Republic in the Battle of the Ebro. He later escaped to France, where he was held in a concentration camp at Argelès-Sur-Mer. A French football club, FC Sète, pulled strings to have him released to sign him for the French League side. He, too, eventually returned to Spain to play for Levante.

Under Franco’s dictatorship, Levante was stripped of the national title and the entire history of that legendary season was erased. The official lie that “football was not played in Republican-Spain” is still repeated in some histories of Spanish Football. Valencia CF, the rival in that 1937 final, has a historical record from the Francoist era that falsely claims that “the club had no official activity” during the war years. These claims have since been completely debunked, as historians have documented well over 400 games played during the Spanish Civil War in Republican-controlled territory alone.

Beyond that erasure of history, the Franco regime attempted to dismantle Levante and all that it had come to symbolize as the darling club of a working-class fishermen community that was staunchly Republican in their sympathies and whose idols were Republican war heroes. Not coincidentally, that same community was the most-bombed area in Metropolitan Valencia by the Nationalists. Between early 1937 and march of 1939, it was hit by at least 400 bombs causing at least 825 deaths, according to historians Felip Bens and José Luis García Nieves, who also had a role in recovering the history of the 1937 Cup. Bens and García, who have written four massive books covering Levante’s 100-year history, document how Levante FC’s stadium, damaged during the war, was later occupied by Franco’s military, leaving the club without a stadium for its matches, land to sell, or compensation from the seizure of the stadium—a virtual death sentence.

Then, in a dictatorial effort to erode the club’s fervent, leftist base, Levante FC were cornered into a merger with Gimnástico, a right-leaning, city-based club born out of Catholic Youth organizations—the virtual antithesis of Levante’s roots. What prompted the merger was the fact that Levante had no stadium—which wasn’t true—and that Gimnástico did not have enough players. In any case, the move displaced the club from its maritime roots in El Cabanyal to Valencia proper, and saw the club assume its current name Levante Unión Deportiva (Levante UD).

Once a regional powerhouse with a nationally-recognized youth system and several long Cup runs, Levante withered away, suffering a series of debacles that condemned it to the lower tiers of Spanish football. The club only managed to climb back up to the Spanish First Division in 1963 and did not sustain itself as a consistent First Division club until the 2010s, when it qualified for a European competition for the first time.

Even amongst fans, the distant memory of the moment when “El Llevant va guanyar una copa” (Valencian for “Levante won a cup”) was buried during the dictatorship and the years of lackluster results. Indeed, a generation of fans not alive during the glory years were stunned when they first heard of a time when their club were giants and champions. Emilio Nadal was one such fan. Though he now works in a formal role with the club, he spent 25 years researching and laying the groundwork for the recognition of the title, he even managed to find the actual trophy, hidden away in an attic. The recognition was the result of a sustained community effort involving everyday fans, club historians, media, lawyers, and club directors. Fans had been demanding recognition of the cup with banners at Levante matches for many years.

Now, Levante fans feel a sense of relief. As García Nieves explains, “We had normalized the situation of non-recognition. Even when everyone knew the Cup was played, that it was legal, and that Levante won, we had normalized a feeling of inferiority because the official recognition never came. This history of ours was at risk of vanishing like an old lament in a grandfather’s tale.”

Finally, 85 years after winning the title, Levante has honored the legacy of its ancestors and restored its rightful place as one of the 19 clubs in Spain to have won a national title. Descendants of both the 1937 squad and early Levante fans can now properly celebrate that title and the historic and noble effort those players and fans made to bring some level of normalcy and joy to a nation under fascist assault. The Spanish Football federation—which found itself out of excuses and cornered by the 2022 Law of Democratic Memory of 2022—has been forced to recognize the title and present the cup before cheering fans in the Estadio Ciutat de València. The trophy serves as a testament to the resilience of historical memory and the perseverance of those who fight to recover it.

Timeline

1937 Levante wins the Cup of Free Spain

2000 Emilio Nadal publishes an article in El Mundo Valencia, returning the Cup to the spotlight, Penya Tótil, a supports club begin making calls for recognition at home matches

2004 Izquierda Unida makes a formal proposition to officially recognize the Cup of Free Spain.

2007 Spain’s Congress officially recognizes the title, but the Spanish Federation continues without doing so.

2018 The Law of Democratic Memory is proposed in Spain, opening a possible route for recognition for the title.

2019 Club directors at Levante redouble efforts for recognition.

2022 The Senate passes the Law of Democratic Memory

2023 The Spanish Football Federation approves recognition of the title and formally presents Levante with the trophy.

Dean Burrier Sanchis is a high school Spanish Teacher and Soccer Coach at Elk Grove High School. His Spanish-born grandfather, Vicente Sanchis Amades, was a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.