The Amazing Tale of Otília Castellví, a Seamstress from Barcelona

The day after Franco’s troops entered Barcelona, Otília Castellví, a young seamstress, woke up to a city she could barely recognize. In her memoir, she wrote:

One at a time, we took turns silently walking onto the balcony to peer through the shades, as if approaching someone on their deathbed, and looked out at the city of Barcelona, searching for anything which might give us hope. We saw nothing that offered us any encouragement. It was a truly horrifying sight: guns strewn everywhere, burnt books and papers in the middle of the streets; men running, terrified, only partially dressed, having thrown away the uniforms that would have identified them. None of us who saw that had any desire to step onto the balcony a second time. The last person who looked out spotted the Spanish monarchy’s and Franco’s flag flying over the Hospital Clínic. That shocking sight meant that for us, the end had arrived. All our eyes filled with tears…It was January 26th, 1939. (…) Death arrived, that day, in Barcelona. We all felt it, and sadly, we were right.

Otília, a member of the POUM, the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (Workers Party of Marxist Unification), went into hiding. She even stayed for a time in a brothel, convinced no one would look for her there, and told the other women she had “health problems” which prevented her from being able to work.

Six months later, Otília decided it was too risky to remain in Barcelona. Carrying only a small backpack and trying to look as if she was just going on a hike, she and a guide walked up the Pyrenees towards France. They spent the night in a shepherd’s hut, and when they woke up the next morning, they could see a steel border marker high on a mountain peak. As they set off, her eyes filled with tears as she thought about everything and everyone she was leaving behind.

They finally reached the top.

“You have no idea how good it felt to be able to yell ‘Death to Franco,’” she told me, before adding, winking, “but of course with one foot over the border.”

They then began to hike down the other side of the mountain, into France. Little did she know she wouldn’t return for twenty years.

***

This was one of the many stories Otília told me when I went to live with her, in 1979. I was fresh out of college, where I’d met her son, Ulisses. When I told him I wanted to go to Barcelona for a year to learn more about Catalonia, he asked Otília if I could stay with her. She lived alone in a large and airy apartment she’d bought when she returned from exile in the late 1950s. Otília wrote me to say I’d be welcome, and generously turned down my offer to pay rent. Instead, she requested only two things of me: that I clean up after myself, and that I speak in Catalan. (Otília and her husband were great admirers of the Lincoln Brigade.)

Otília gave me a typewritten copy of her memoir, which she’d written as a gift for Ulisses. She entitled it “Twenty Years of a Life: 1926-1946. A Simple but True Narrative.”

The title was misleading. Otília’s story was anything but simple.

***

Otília was born in 1907 and raised in Gràcia, a working-class Barcelona neighborhood. Her mother died when she was young, leaving her father to raise nine children. She left school after third grade and went to work as a seamstress when she was twelve.

Although Otília never saw herself as political, she had what she described as an instinctual belief in Catalan nationalism. She was also committed to workers’ rights. Sewing was seasonal work, and workshops closed for several months each year. Otília began sewing for a wealthy client, who one day came to her complaining about workers’ protests, arguing they didn’t deserve to be taught to read. Otília put down the dress she was working on, and told the woman she should look for a donkey to finish sewing it. She wrote, “I walked out, both angry and a little worried, since I no longer had a job. I felt deeply satisfied that I’d been able to successfully make the life of a member of the privileged upper class a little harder, since she needed to have the dress ready that night.”

Otília joined a hiking club, where she quickly fell for a young student, Llorenç. They shared a suspicion of religion and a belief in using social welfare to address class divisions. She listened eagerly to his explanations about politics, and they soon became inseparable.

One Sunday in 1932, she decided to attend a meeting of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Bloc. She was enthralled by the crowd’s passion, and asked the men standing next to her if she could join the party. She became the first woman in her neighborhood cell; she didn’t say much in meetings at first, but gradually became more involved:

They soon became comfortable assigning me tasks which were more likely to be successful if a woman took them on: selling our newspaper, “La Batalla,” on the streets, putting up posters, and painting slogans on walls. If some of the men took these on, they often brought me along as an accomplice. When we were done, we would stroll away together, arm in arm, as if we were a couple, laughing at the police and the entire world.

In October 1934, in reaction to a right-wing party joining the Spanish government, left-wing parties called for a general strike. The Madrid government responded by calling out the Guardia Civil. The Catalan government’s soldiers surrendered. Otília’s involvement soon went well beyond selling newspapers and painting graffiti. She and others found piles of guns that had been left on the street by some of the soldiers, and headed toward where the fighting was still going on. She suddenly found herself in a small truck belonging to the Hotel Ritz:

Some members of the Guardia Civil got off their bus and started firing at us. (…) The Mausers’ bullets zipped right by us, although a few entered the truck, with that loud whistle from the afterworld announcing death was nearby.

The woman sitting right next to her was killed, as were two of the men.

On July 18th, 1936, Franco staged his coup to overthrow the Spanish government. In Barcelona, the Catalan police, anarchists, other left-wing parties and the Guardia Civil quickly defeated Franco’s soldiers. Otília volunteered in a makeshift hospital in a theater on the Ramblas.

Meanwhile, an internal struggle was growing within the left. The Stalinist-controlled Communist Party’s “Txeca”—the secret police—began their campaign to suppress other left-wing parties, including the much smaller POUM.

Despite her activism, Otília was profoundly disappointed by the infighting:

I have always felt disgusted by politics. Even though I found myself in the very nucleus of a political party, I have never been interested in politicians’ complicated strategies (or self-interested maneuverings?). Not while I was a militant in the POUM, nor before, nor afterwards. (…) During our revolutionary struggle, just as in my youth, my own rebellion was more sentimental than theoretical.

The price Otília paid for being involved in the “revolutionary struggle” suddenly became much higher when an electrician forgot to turn off a light after doing some repairs in Llorenc’s family’s apartment. Because of Franco’s bombings, it was forbidden to have any lights visible from the outside. The police chief, a Stalinist, saw the light as proof the POUM had been collaborating with the fascists and ordered Llorenç, his family, and Otília to be arrested.

More than feeling afraid, Otília walked into the women’s prison excited at having the opportunity to experience it for herself. She joined a hunger strike and later got into an argument with a leader of the fascist youth group, whom she punched in the face. When the prison’s director came to reprimand them, the fascist began to hurl insults at Otília, but before she could finish her sentence; Otília punched her again, right in front of the director, who then separated the fascists from the leftists.

Otília was released but was soon arrested again, this time by the Txeca’s agents, who took her to one of their secret jails (also called “txeques”). She refused to confess to her interrogator’s false accusations:

I will not deny how the atmosphere there, and everything I knew about the Txeca, made my heart pound. But more than fear, I was so angry and indignant, that instead of letting him see me cry, I clenched my teeth and kept my eyes (which likely betrayed what I was really feeling) focused on that monster.

In response to her silence, her interrogator sent her to solitary confinement in a cell with no bed, no chair, and no toilet.

The day Franco’s troops entered Barcelona, Otília was still in the txeca, wondering if she and the other prisoners would be shot by the communists or the fascists. Although the guards had been ordered to leave, the one Catalan speaker among them stayed behind. Once he was sure the other guards were far enough away, he came back and opened their cell doors. Otília went to Llorenç’s home and into hiding.

***

France was anything but welcoming. Llorenç arrived soon after she did, but they were both jailed and then sent to an internment camp at Argèles-sur-Mer. They were separated, and Otília spent four months living in a crowded barrack with sand floors and walls with large gaps between the boards, allowing the wind and cold to come in. Due to a nearly total lack of hygiene, she nearly died; she also became infected with scabies, which took nearly a year to cure.

Llorenç was sent to a work camp in northern France, and Otília was given a permit allowing her to live in Dijon. The day after she arrived, she met Linus, a resourceful, gregarious POUM member from Barcelona. Linus soon became her protector, helping her find work and a place to stay. He also assisted her in her attempts to join Llorenç.

However, she was arrested once again, this time under false charges of having ignored orders to return to Spain. When the Germans began bombing Dijon, the prison staff evacuated the prisoners and sent them on a forced march to Lyon, 120 miles away. By now, Otília had begun to wonder if it wouldn’t be better if the Nazis took over France entirely.

A young woman whom Otília knew from prison walked behind her at the end of the long line of prisoners. She repeatedly collapsed on the ground, moaning, saying she was pregnant. A soldier granted Otília permission to stay behind and take care of her, as long as they promised to catch up with them in the next town:

Sitting on the side of the road, groaning as if half dead, the pregnant woman leaned against me, seemingly unaware of anything going on around her, while I looked, with some anticipation, at that pathetic parade moving along the road. When the last gendarme disappeared around a curve, that ill woman stood up as fast as lightning, and proposed we get as far away from the march as possible. Although her quick transformation surprised me, I immediately recovered and told her I couldn’t think of anything I wanted more.

Otília made her way back to Dijon, where she found Linus. Together they decided the risks of her being arrested again and sent back to Franco’s Spain, were too high. Linus proved his resourcefulness once more and was able to obtain forged papers allowing them to travel to Luxembourg.

However, after spending a month there, they were unable to find work. Melitta, a German friend whom Otília had met in Barcelona, wrote to invite them to come to Germany, telling them they would have nothing to fear and would be able to find jobs.

On August 21, 1940, Otília and Linus, with great trepidation, crossed the border into Nazi Germany. After her exceedingly unpleasant reception in France, she was surprised by the Germans’ welcome:

The Germans deserve respect, since I was able to get my papers quickly. They gave me a permit to work at home as a seamstress, with the same conditions and ration cards as any German citizen. I was also surprised by how well I was treated everywhere I went, since all of us who were anti-Nazi held such strong preconceptions about them. The terror in Hitler’s Germany must have been well hidden, since in daily life neither the German people nor we foreigners had any sense we were living under such a barbaric regime, especially when it came to politics.

Linus found work in a mine in Saarburg, just over the border from Luxembourg. Melitta invited Otília to live with her in Frankfurt, and found her clients, who needed sewing done. Otília was filled with mixed feelings: she was glad to have a home and to be able to earn her keep, but desperately homesick for Barcelona; amused by the Germans’ eagerness to meet an exotic Spaniard, but also annoyed at their childish fascination. She also felt conflicted when Melitta’s younger brother was sent to the front:

I couldn’t stand to see such an intelligent, young man so full of life march off to his death. (…) He was a member of the SS, so in theory, he was one of our worst enemies. However, I had known him in his private life, and knew what a sensitive soul he was. I trembled at the thought of his being associated with the atrocities of Hitler’s fanatical youth. I felt no hatred towards him.

Linus moved to Darmstadt and invited Otília to join him there. He found her a job working in a delicatessen. She gave extra rations to Jewish customers, who were forbidden from buying the same amount as others.

Soon afterward, Llorenç wrote her to break off their relationship.

He repeated over and over again how much he loved me, and how I was the best thing that had ever happened to him, but then bluntly told me that current circumstances made him realize that personal relationships were no longer important during such a difficult time for all humanity. He said that his independence was crucial, in order to have the total freedom he needed to be able to act. (…)

My political ideals had come to nothing. Now, love had as well. Nothing made any sense anymore.

Otília spent months in a deep depression. She was only shaken out of it when Gestapo agents arrested Linus. They released him after four days, with a warning to be more careful before sharing his political opinions with others. But the threat of losing him made her realize how much he’d done for her. They soon became a couple, and because it was forbidden for an unwedded couple to cohabitate, married.

Otília and Linus miraculously survived more bombings in Darmstadt and Frankfurt. They moved to a small village, where they stayed for more than a year. They were delighted by the peace and quiet, which lasted until the Allies began bombing the village.

Otília saw that many of the first U.S. soldiers to arrive were Mexican Americans, and was horrified to see them used as cannon fodder. When Linus and Otília spoke to them in Spanish, some burst into tears, and fell into their arms. Otília helped them write letters to their mothers, aware it might very well be the last time they’d hear from their sons.

After spending nearly all of World War II in Germany, in April 1945, Otília and Linus were able to make their way to Paris. Otília became pregnant. Linus found a well-paying job with the telephone company, but after two months, the labor union told him that as a refugee he was could no longer keep that position. Otília wrote:

Utterly disgusted, and getting close to hating all of France, and the conceited French, we desperately began looking for a way to leave the country of Liberté(?) before our baby would experience the misfortune of being born there.

Linus was able to obtain tickets from a British charity for passage to Venezuela. When they arrived in Caracas, Otilia seemed more terrified by cockroaches than by many of the threats she’d faced in the previous twenty years. Linus found work in a bookstore. They soon had enough money to rent an apartment in a brand-new building, where the odds of there being cockroaches were lower. A few weeks later, Otília gave birth to Ulisses.

Linus adapted well to life in Caracas, but Otília never did, and was eager to go back to Catalonia. After they obtained Venezuelan citizenship, they determined it was safe to return, even though Franco was still in power. Otília, committed to raising Ulisses in a Catalan environment, brought him back to Barcelona in 1959. Linus stayed in Caracas, but came to visit once or twice a year.

Llorenç remained in the resistance for some time, helping English prisoners who had come to fight in Spain return home. He’d been arrested and sent to prison. By the time Otília returned home, he had married and had two children. Out of respect for Llorenç’s family, she gave him a pseudonym in her memoir.

In 1996, Otília gave her manuscript to her friend Enric, who quickly began to look for a publisher. He was successful, and on the day he received the galleys, he called to tell Otília. Any other day Otília would have been happy to hear the news – but just a few hours earlier, she learned that Llorenç had died.

Just before the book went to press, Otília suffered a stroke, and was rushed to the hospital.

It’s impossible to know if she was aware of her book being published.

Linus died in April 2000; Otília eight months later. In response to advocacy from a feminist organization in Gràcia, Barcelona’s city government named a street for her, not far from where she grew up.

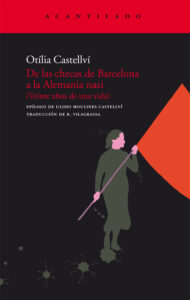

In 2003, her book was released again by a new publisher, first in Catalan and then in Spanish. I’ve just finished translating it into English as a way to honor her. The new publisher gave it a new title, which begins to convey the uniqueness—and not at all simple—story of a woman discovering her own strength, a woman who for many years was without a country, a woman who fought authoritarianism: “From Barcelona’s Secret Prisons to Nazi Germany.”

The translation from Catalan of Otília’s memoir was undertaken with the support of the Institut Ramon Llull.