Stuart Christie’s Unending Struggle

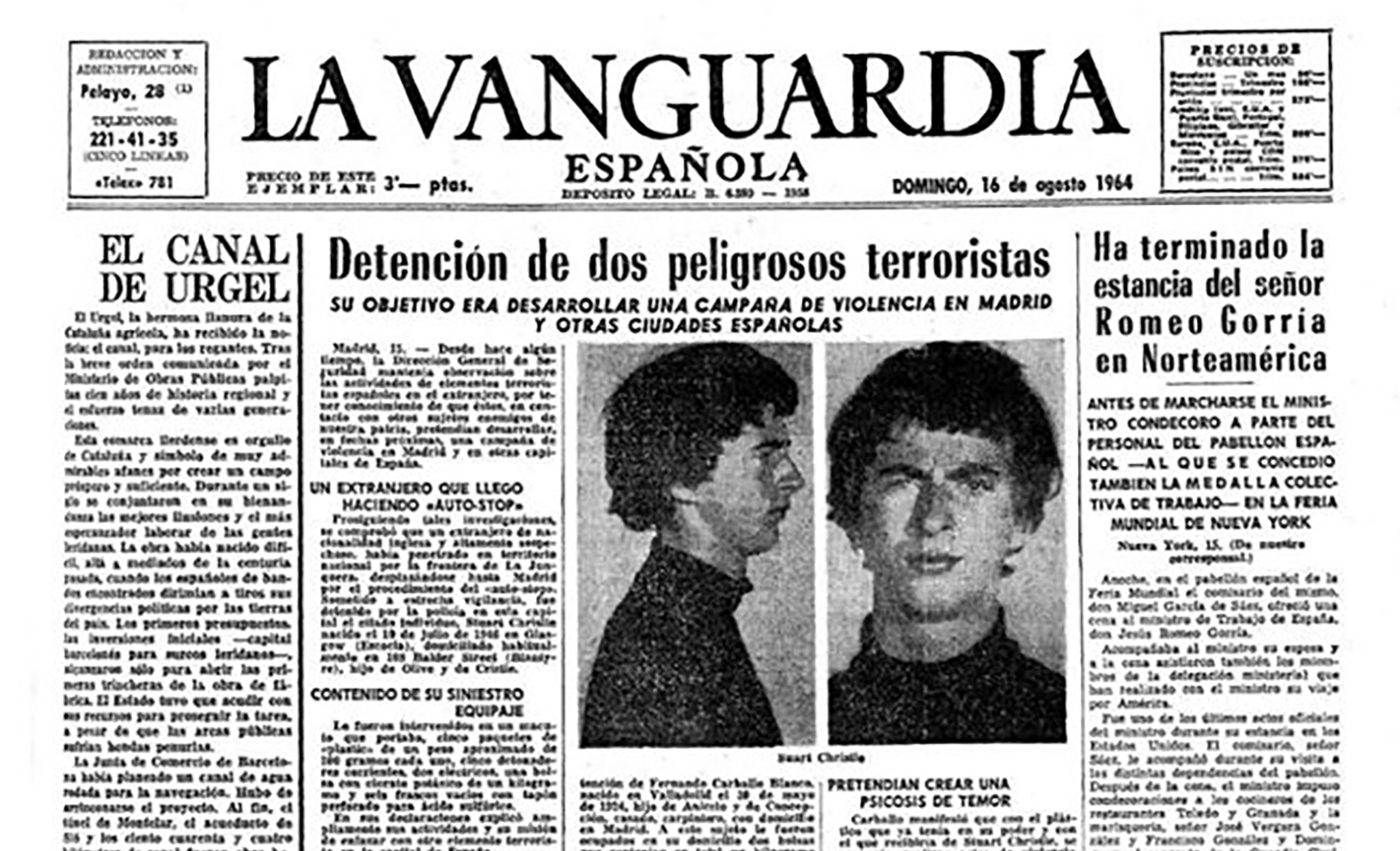

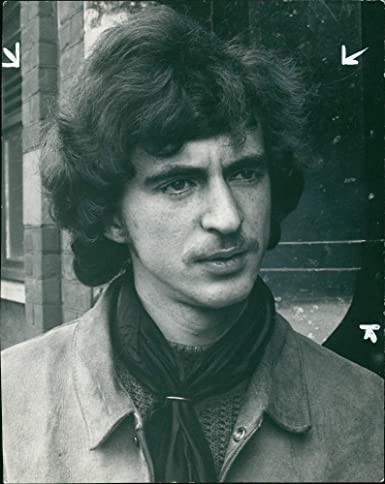

Stuart Christie, who died in August 2020, was best known as the 18-year-old Scottish anarchist who, in the summer 1964, was part of an attempt to assassinate General Francisco Franco. It was only the beginning of a long life dedicated to left-wing activism.

By the time Stuart Christie volunteered to transport explosives for the 1964 plot to kill Franco at the Santiago Bernabeu soccer stadium in Madrid, his acquaintance with anarchism in the UK had been building for some time. As he explains in his entertaining memoir General Franco Made Me A Terrorist (2003), he had also been in touch with Spanish exile circles in France. Yet before the attack could be carried out, Christie was arrested by undercover Spanish police.

Born into a working-class family in Glasgow, he had come into contact with local anarchist groups in his earliest youth and began reaching out to libertarians around the world. His association with the Spaniards during the 1960s was overshadowed by the execution in Spain, in August 1963, of Francisco Granado and Joaquín Delgado, anarchists from the Libertarian Youth. He would subscribe to the working-class anarchist tradition for the rest of his life.

The fact that Stuart failed in his attempt to kill the dictator did not spare him from a passage through Spanish prisons. Having dodged the death penalty, he was sentenced to 20 years. In Carabanchel, where he came upon lots of anarchists and communists (though no socialists, as he liked to point out), he worked in the prison print shop, learnt Spanish, and studied for admission to a British university. He was released in 1967 thanks to an international pressure campaign that included, among many others, Bertrand Russell and Jean-Paul Sartre.

On returning to the United Kingdom, Stuart was in the sights of the British police, who fabricated evidence showing him to be a member of the notorious Angry Brigade. Even though none of the charges could be made to stick and he was acquitted, he spent 18 months in custody in what was one of the lengthiest trials in British history.

Eventually, Stuart would be the first in his family circle to attend university; in the early 1980s he made his way to Queen Mary College (University of London) where he studied History and Political Science. At the Centro Ibérico, he met the historian Paul Preston, who was then lecturing at that university. His interest in the history of anarchism led, among other publications, to one of the few existing books on the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI), We the Anarchists, published in Spain by the University of Valencia Press. From very early on, Stuart was concerned at the resurgence of far-right groups across Europe and at the strategies these employed in the 1970s and 1980s. Given the current panorama in Europe and worldwide, his work remains highly relevant.

Stuart’s committed activist anarchism prompted him to resurrect the Anarchist Black Cross to defend libertarian prisoners worldwide. Realizing that the best way of spreading anarchist beliefs is through education, and in line there with anarchism’s most classical values, he also committed himself whole-heartedly to the study of anarchist history. In 1969 he launched one of the most significant imprints in the field, Cienfuegos Press, which he ran from the Orkney Islands, in remotest Scotland, due to persistent police harassment in London. In addition to books, he also used newspaper projects as vehicles for his beliefs. Cienfuegos Press was followed by Christie Books, an imprint that he carried forward until his death and that made classics of anarchist history accessible on-line, translated into English by Christie and Paul Sharkey. Later, the Christie Books website would feature the popular Anarchist Film Archive.

Stuart was loyal to an ideal, to a cause, and to his friends and comrades. A highly educated man, he also was a tireless, yet patient publisher, a great lover of words with a belief in their ability to work changes in human beings. With his death, the international anarchist movement has lost a great stalwart. A degree of solace is provided by the Kate Sharpley Library Collective’s recent publication of A Life for Anarchy: A Stuart Christie Reader, a collection of Christie’s writing spanning more than five decades. The KSL editors have included a brief introduction, a series of instructive footnotes, and a very handy glossary that will be helpful for younger readers and for those less familiar with the history of the European anarchist movement.

Stuart believed in the importance of studying the enemy, witness his book on the Italian neo-fascist Stefano Delle Chiaie. Similarly, in one article, he references Low intensity operations: Subversion, Insurgency and Peacekeeping, a Machiavellian handbook written in 1971 by the imperialist thug General Sir Frank Kitson, designed to allow the defenders of a crisis-ridden state to steady the ship in the face of spiraling dissent. In the UK at the time, this tension played out with rising state and police repression, the erosion of civil liberties, the one judge conveyor-belt Diplock Courts in British-occupied Ireland and bloated Special Branch resources.

Another of Stuart’s core attributes—his unflinching humor—comes through in the KSL collection as well, even in the most adverse circumstances, such as during his time in Carabanchel jail. In his inimitable style, we read how he received a monthly money order from the exiled Spanish CNT in Toulouse: “The names of the remitters were, in rotation, George, Paul, John and Ringo, the only English names known to the political prisoners’ support fund, all of which led to the rumor that I had been bankrolled by the Beatles, something which gave me considerable kudos among my fellow prisoners.”

Finally, we see ample evidence of Stuart’s love of language and erudition. I was always struck by the breadth of his culture, in his writing and conversation. We worked together on the English-language edition of José Peirats’ The CNT in the Spanish Revolution for Christie Books. Besides appreciating his qualities as a patient and attentive editor, I was impressed by his literary references, which ranged from obscure Scottish poetry to popular culture; this was always very natural, lightly worn, in no way jarring or artificial. He always displayed immense enthusiasm and optimism.

Chris Ealham is a historian based in Madrid. This text includes parts of two previous publications, both of which appeared on the website of the Kate Sharpley Library; an obituary written in collaboration with Julián Vadillo Muñoz, and a review of the Stuart Christie Reader.