Rewriting Black History: Langston Hughes in Spain

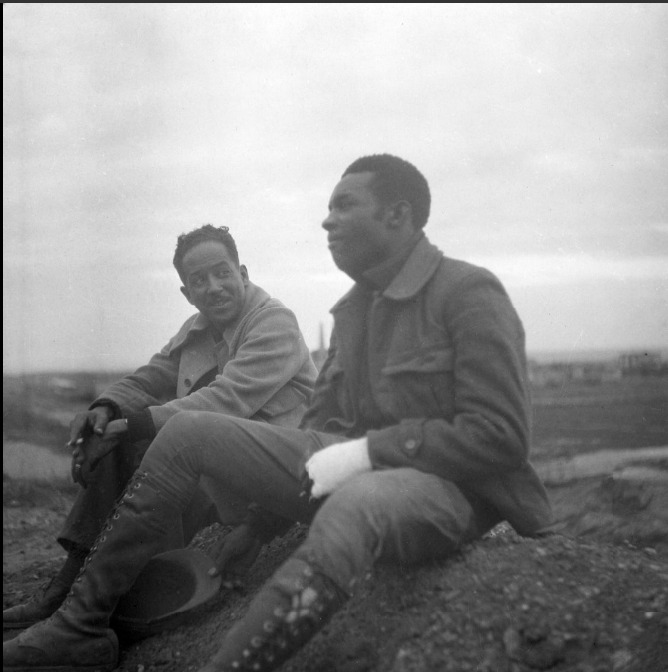

Langston Hughes (l.) and Crawford Morgan [with bandaged hand] at Fuentes de Ebro, Oct. 1937 (Tamiment Library, NYU, 15th IB Photo Collection, Photo #11-1347).

Yet for African Americans who had sympathized with or joined the US Communist Party in a period when it was the only institution that offered a multiethnic agenda, the war in Spain was more than an opportunity to oppose international fascism. It was a chance to avenge Mussolini’s 1935 attack on Ethiopia, which stood as a symbol of ethnic purity and resistance against external occupation. Given the military superiority of Italian troops and the lack of coordination of international support for Ethiopia, little could be done in its favor at the time. “We Negroes who have been in Spain are a great deal luckier than those back in America,” Walter Garland, an African American from Brooklyn and commander of the legendary Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, said, because they had “been able to strike back … at those who for years have pushed us from pillar to post”. Robin D.G. Kelley and Antonio Celada estimate that nearly 90 people of African descent joined the International Brigades from the United States.

For Black communities across the country, the story of Black Americans in Spain was shaped decisively by the poet Langston Hughes, who was sent over to cover the war for the Baltimore Afro-American, but whose stories were distributed through the Black press nationwide. In a way, his journalism was the first homage to the African Americans who fought in the Spanish war. More than a half of Hughes’ articles, Josh Roiland points out, are “profiles of everyday soldiers who he feels have made a meaningful difference while volunteering for service in Spain,” reflecting Hughes’ conviction that African Americans needed “names to be proud of”. As Hughes wrote in his piece “‘Organ Grinder’s Swing’ Heard above Gunfire in Spain” (Nov. 6, 1937): “the most interesting colored people one meets … [are] those you never heard of in any book. (But you will, in due time, no doubt.)”

He writes about Salaria Kea, a “charming nurse at one of the American hospitals in Spain,” and about the heroic death of Milton Herndon, who “died not only to save another comrade, or another country, Spain, but for all of us in America, as well.” Abraham Lewis, Hughes writes, “is proud of the opportunity which the International Brigades have given him to make use of his full capacities,” something that was rare back in the States. Thaddeus Battle, who had left Howard University, pointed out to Hughes that “colored college students must realize, too, the connection between the international situation and our problems at home.” By writing of people like Walter Cobb, Ralph Thornton or Basilio Cueria, Hughes in a way started carving the names of those he thought deserved to be included in future monuments or history books.

Hughes’ dispatches should be read alongside his poetry about the Spanish war. The points he makes are the same, but his journalistic work is more straightforward. Take, for instance, a fragment from his article “Soldiers from Many Lands United in Spanish Fight” (December 18, 1937): “Fascism is what the Ku Klux Klan will be when it combines with the Liberty League and starts using machine guns and airplanes instead of a few yards of rope. Fascism is oppression, terror, and brutality on a big scale.” By comparison, in “Love Letter from Spain” (1937), an anonymous volunteer in Spain tells his beloved at home that “Fascists is Jim Crow peoples, honey – / and here we shoot ‘em down.”

Hughes’ dispatches should be read alongside his poetry about the Spanish war. The points he makes are the same, but his journalistic work is more straightforward. Take, for instance, a fragment from his article “Soldiers from Many Lands United in Spanish Fight” (December 18, 1937): “Fascism is what the Ku Klux Klan will be when it combines with the Liberty League and starts using machine guns and airplanes instead of a few yards of rope. Fascism is oppression, terror, and brutality on a big scale.” By comparison, in “Love Letter from Spain” (1937), an anonymous volunteer in Spain tells his beloved at home that “Fascists is Jim Crow peoples, honey – / and here we shoot ‘em down.”

Hughes’ experience in Spain clearly shaped his understanding of US racial oppression in global terms. “Negroes from all over the world [are] here”, he wrote in The Volunteer for Liberty, “because they know that if Fascism creeps across Spain, across Europe … there will be no place left for intelligent young Negroes at all.”