Faces of ALBA: “Students Are Drawn to Antifascism”–Michael Koncewicz

For close to ten years, the historian Michael Koncewicz, the Michael Nash Research Scholar at Tamiment Library, worked with the ALBA collection on a daily basis. In April, he left the library to become Associate Director at NYU’s Institute for Public Knowledge.

The author of They Said No To Nixon: Republicans Who Stood Up to the President’s Abuses of Power (2018), Koncewicz is currently working on a biography of Tom Hayden, a key figure in Students for Democratic Society (SDS). A co-author of the Port Huron Statement and a prominent anti-Vietnam-war activist, Hayden was one of the Chicago Seven, husband of Jane Fonda, and, starting in the mid-1970s, active in California State politics.

You came to the Tamiment from the Nixon Presidential Library. That’s quite a transition.

I must say I ended up at the Nixon Library more or less by chance. I’d started my Ph.D. at UC/Irvine in 2008, right when the economy was collapsing. It spurred me to look for summer employment. I’d always been interested in public history and education work. My advisor, Jon Weiner, took our Cold War class on a trip to the library, where we met the director, Tim Naftali. The connection was quickly made. I first did an internship and then became assistant to the director. After Naftali became head of Tamiment in 2014, he suggested I apply to run the Cold War Center here, alongside [Professor] Marilyn Young.

Still, you wrote your dissertation and first book about Nixon.

To be precise, it’s about the figures in the Republican Party who stood up to Nixon. When I first got to Irvine, I’d planned to work on antiwar journalists during the Vietnam era. That project eventually became an article. While preparing the Watergate exhibit at the Nixon Library we kept running into stories of Republicans who said no to Nixon. Jon Weiner and I figured there was a book there.

Over the past 15 years, you’ve moved back and forth between writing about the Left and the Right. Do those histories feel very different to you?

The archives are certainly different, even if the issues surrounding those archives have some similarities. In my experience, people on the left are more eager to talk in greater detail about their histories. Only a few of those I reached out to for the Nixon book were willing to talk to me. For the Hayden book, it’s a different story altogether.

In both cases, though, you’re steeped in the 1960s and ‘70s.

Absolutely. Of course, Nixon and Hayden were dramatically different characters. What links them, though, is that they were both political strategists who were defined by the New Left, albeit in very different ways. Both books, in the end, are about people who are conflicted about their own political identity. The Republicans who stood up to Nixon were in favor of a more diplomatic approach to New Left social movements that Hayden represented. They were trying to figure out what the relationship of the state to these movements should be. Hayden, from his end, was trying to figure that out, too.

A biographer, I’ve been told, enters into a special and often intense relationship with her or his subject. When I interviewed Richard Evans about his Hobsbawm biography, he told me that, when he’d finished, his wife was happy to finally get rid of their live-in dead roommate…

(Laughs.) Yeah, my wife is certainly sick of my trying to squeeze in a conversation about Tom Hayden when our six-year-old is demanding our attention. But the truth is that I’ve always admired Hayden. I met him only once, when he gave a book at talk Irvine in 2011. He’d brought his own books to sell, in a bag, and not only gave me a deal on them because I didn’t have enough cash on me, but stuck around to talk with me and a fellow grad student about our own experiences with student activism. I’d been an antiwar activist as an undergrad at Central Connecticut University, a small commuter school, from 2002 to 2006, and Hayden was very interested to hear about our group dynamics. It was a great conversation. When I first talked to Tom’s last wife, Barbara, and his son Troy, they were visibly relieved to hear that my encounter with him had been a nice one.

Had they expected differently?

Well, he had a well-deserved reputation for grumpiness. But their reaction prepared me for handling Hayden’s many complexities—not only his own personal demons and flaws, but also how he was seen by those who worked with him, from SDS and the broader antiwar movement to people in the California state legislature. Their relationship to Hayden tells us a lot about the way people on the left view leadership, and about Hayden’s lifelong quest to be an insider and an outsider at the same time.

How critical of Hayden will your book be?

When I first talked to Al Haber—who’s 86 and still lives in Ann Arbor—he asked me if I planned to write a puff piece. He’d heard that this was going to be an authorized biography and that I was working with the family. I said: “No, that’s not my goal,” and gave him my pitch. “That sounds good,” he said. “Tom deserves a lot of puff—but don’t give him a puff piece.” The family knows what I’m going for. They are supportive of an independent, critical biography.

There’s been a certain nostalgic fascination with the 1970s of late. I’m thinking of miniseries like Ms. America, about the Equal Rights Amendment, and Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago Seven. How do you feel about that?

Sorkin’s movie has some very serious flaws. But I’m glad it’s out there, because helps people understand what I’m writing about and makes for a nice entry point to conversations. In general, it’s great that there is a mini boom of interest in the period. And I am encouraged by the fact that some projects—not Sorkin’s, but other documentaries and podcasts—are less reliant on memoirs and more focused on social movements.

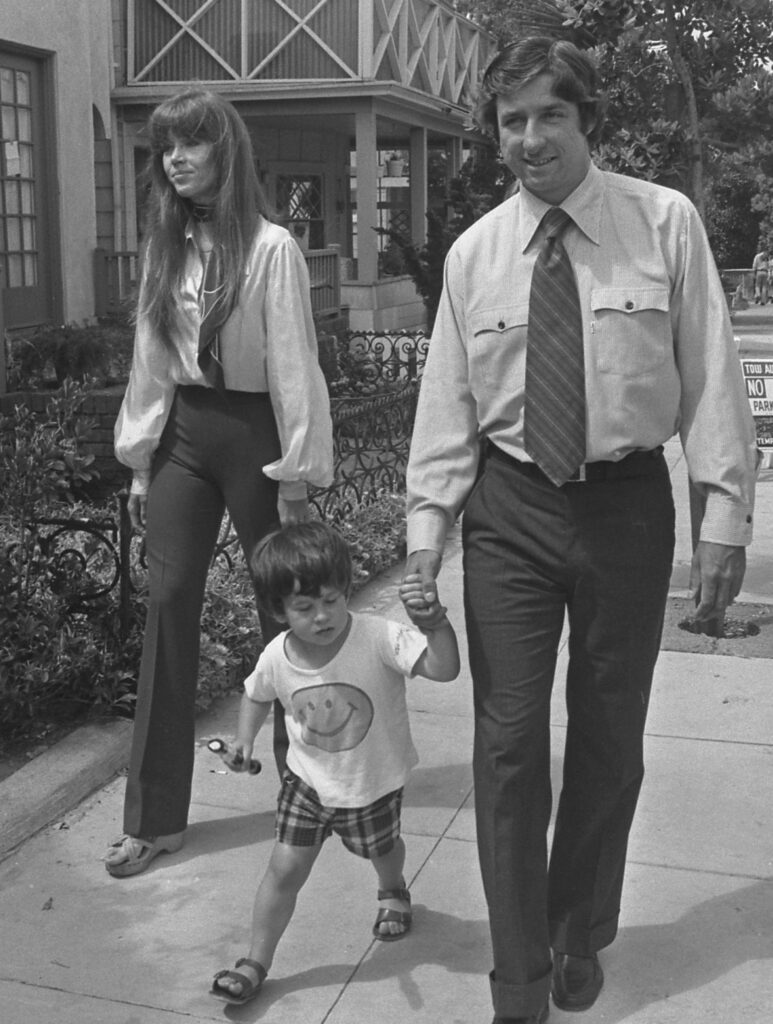

Tom Hayden, his wife, Jane Fonda, and their son, Troy, walk to polling place near their Santa Monica home, 1976. Photo William S. Murphy. CC BY 4.0.

Hayden was also something of a celebrity.

Yes, he’s part of American popular culture, and not just because he was married to Jane Fonda. There are few figures from SDS who get brought up in an episode of The Simpsons! (Laughs.) Seriously, there’s something unique about Hayden’s own life and his network. It’s one of a kind. So far, I’ve interviewed more than 70 people. On the same day, I may talk to a former gang member whom Tom mentored and then brought into his state Senate office to work for him, and then to a Hollywood actor who was one of his close confidants. Then, the next day, I may speak with someone who was at Port Huron, and the day after that, to someone who was part of the Weather Underground. It’s crazy.

As you said earlier, he straddled different worlds.

Exactly. It also shows how the New Left influenced American culture and politics, even if in the end they lost out to the neoliberal turn in the Democratic Party.

Will you be tempted in your book to draw political lessons for the present?

Yes, I think I will—and I’m being encouraged by several people to do so. Those lessons are there, both in things that Tom did and that, if he were alive, he’d probably admit he would do differently. I think recent work on the New Left has been too quick to dismiss it for its rejection of the Old Left and its focus on individual rights, which—the claim is—helped pave the way for the rise of neoliberalism. There’s something to that argument, but anyone who’s a bit more knee-deep in this history knows that is a little too neat of a story, if not a caricature. If you go back and reread the Port Huron statement, for example, you’ll see that the line between the Old Left and the New is murkier than most people assume. The statement is much less anti-union than it’s made out to be. Plus, there’s a reason people are mad at the unions in the 1960s. I mean, should SDS have supported the war in Vietnam, as the unions did?

At the Tamiment, you’ve been knee-deep in the Old Left every day. How have these ten years changed your views of the 1930s and its legacies?

That’s a good question. I’d say my views have improved. On the other hand, it could hardly be otherwise: if you’re working with these materials on a daily basis and your own politics are leftish, you’re going to be predisposed to just liking these people and organizations. Having said that, I was never one to pick sectarianist fights, even as a student activist in Connecticut. I took pride in that and I still do. That also means I never really had any generational anger towards the Old Left, the New Left, or the current left. That’s just not who I am. So while my respect for 1930s left wing-history certainly increased as I learned more about it at Tamiment, it was not some sort of dramatic shift for me. I’m very interested in figures, moments, and movements that take a big-tent approach to organizing. That’s perhaps one of the reasons I was recruited to do the Hayden project. Hayden was never above picking fights with certain groups and pissing people off, but in the end he was committed to that big-tent approach as well. I mean, for all the differences between the Old and New Left, the SDS kids in 1962 were protecting a Communist so he could attend their meeting! As much as they criticize the Old Left, they actually wanted to preserve the space that existed in the 1930s.

Another lesson to draw from Tom Hayden’s life relates to the importance of institution building. As much as he was known as being someone who was in favor of horizontal organizing and decentralization, he was one of the few figures from the New Left who really prioritized institutions, particularly in his later years. Given what’s happened on the left over the last several years, what I’m struck by is that younger people are not really interested in this debate about whether or not you should have an inside or outside strategy. Instead, more people are willing to try both. Hayden’s work in California is an example of that, but the Tamiment archives also show that there were also plenty of radical activists in New York, say, who tried to maintain a relationship with Albany, so to speak.

Why should people twenty years younger than you be interested in the history of the Left, Old or New?

That’s a big question. Over the past ten years, I’ve taught in traditional classroom settings at CUNY and NYU, but also a lot in the Tamiment classroom spaces when groups come to visit the archives. When I started doing that, in 2014 or 2015, it was a challenge to get students to care. That changed in 2016-17, when it suddenly became a much easier sell to get students interested in antifascist movements. This is especially evident with the ALBA collections. I saw it continue to expand, even during the pandemic when we’re teaching online classes.

What does that tell us?

I think present-day events are doing a lot of the work to get students to care—whether it’s the Old Left or the New Left or any sort of movement or organization that has fought for worker rights, fought against fascism, and fought for a better world. I have seen students making clear links between the past and the present and looking through journals of activists from 110 years ago and understanding their concerns and seeing how it’s relevant today.

Sebastiaan Faber teaches at Oberlin College.