Musical Legacies of the Spanish War: The Strange Case of Gaspar Cassadó

While the cellist Pablo Casals became an international symbol for Catalan culture and anti-Franco resistance, the reputation of his pupil Gaspar Cassadó is limited to the music world, and his national roots are often overlooked. Cassadó’s reputation never fully recovered from a public fallout with his maestro.

The lives of musicians have long been deeply affected by international conflicts. Globe trotters by trade, they travel far and wide seeking education and mastery of skills, looking for admittance into the right intellectual and artistic circles to stimulate their creativity and launch their careers. In the process, many have found themselves uprooted, facing forms of exile and forced migration that, in some cases, end up transforming the musical landscape of their new and adopted homelands. The war-ridden twentieth century is full of examples of musicians embroiled in political affairs or caught in ideological battles that were not always of their own making.

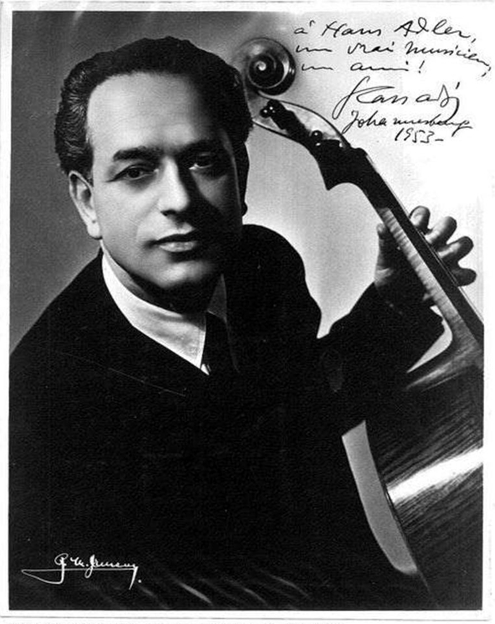

While most readers will be familiar with Pablo Casals (1876-1973), few, even in Spain and Catalonia, will know the name of Gaspar Cassadó. Both were world-renowned cellists with important careers. Cassadó (1897-1966) is also a respected composer of classical music whose pieces continue to be played by cellists around the globe. Still, while Casals continues to be an international symbol for Catalan culture, Cassadó’s reputation is limited to the music world, and his Catalan—or even Spanish—roots are often overlooked.

This imbalance can perhaps be attributed to the fallout of the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath. Casals’s prestige as one of the most respected soloists of the twentieth century is intimately connected to the defense of the Second Republic during the Spanish Civil War and his opposition against the Franco dictatorship—a stance that later earned him the US Presidential Medal of Freedom, awarded by John F. Kennedy in 1963. Cassadó’s recognition amid musicians, by contrast, is almost apolitical, even though his own career, too, was deeply impacted by the war—most notably in March 1949, when the New York Times published a letter by Casals himself in which he suggested Cassadó had been less than critical of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Francoist Spain.

The real story is more complicated. Gaspar Cassadó Moreu was born in Barcelona to a family dedicated to music. His father, Joaquim Cassadó i Valls (1867-1926), was not only the organist for the La Mercè church in Barcelona, but also the founder of the choir Capella Catalana, a conductor at the Teatre de Liceu, and a well-known composer. His brother Agustí was an accomplished violinist who died during a typhoid outbreak at the beginning of the First World War. His sister Montserrat was also a cellist and Josep, the youngest, fought in the Spanish Civil War. His mother, Agustina, ran a well-known piano shop in the city.

Around 1908, Casals heard the young Cassadó play when his father took both of his sons to the French capital to study, and where they also regularly performed as a trio. Casals was not interested in taking students but made an exception for Gaspar. Cassadó also took up composition, learning from composers active in the French capital before the war, including Manuel de Falla, Alfredo Casella, and Maurice Ravel.

After the Spanish Civil War Cassadó moved to Italy and tried to relaunch his career, an effort put on hold by he outbreak of World War II. In 1949, he was due to tour the United States, when the fact that the publicity materials mentioned his connection to Casals sparked an unexpected controversy. Diran Alexanian (1881-1954), another student of Casals, contacted his maestro and received a scathing letter that Alexanian shared with the paper. “During the war,” Casals wrote, “Cassadó made himself a brilliant career in Germany, Italy, and Franco Spain.” To present himself as Casals’ student, the maestro added, showed a “presumption” that “knows no limit, when knowing that I am undergoing exile for having played the opposite card, he uses my name to cover himself. A revolting cynicism!”

Cassadó, shocked by his maestro’s accusations, penned a response that was published a month later. “The inquisitorial tone” of the letters, he wrote, accused him “of crimes I did not commit.” “During the Spanish Civil War I did not take sides,” he added, “having always been an ‘apolitical,’ a great failing in our times, without question. My only brother fought with the Loyalists.” He pointed out that he’d only played once in Nazi Germany and did not play in Italy during the war. Scholars and writers who have examined this story have wondered about the maestro’s lashing out at his once favorite disciple, as there is nothing in Cassadó’s career or life that deserved such characterization. With more scrutiny, it is easy to see that Casals, already over sixty by the time the war ended, was feeling anxious about his own musical legacy interrupted by war and exile and beginning to harbor mixed feelings about the success of others, including his onetime pupil.

Cassadó, who could not bring himself to say anything negative about his beloved teacher, ended up cancelling his tour. A few years later, by the mediation of renowned violinist Yehudi Menuhin, who remained a faithful friend to both maestro and disciple, they reconciled and remained in good friendship. Still, Cassadó’s reputation never fully recovered, and his untimely death in 1966 contributed to his relative obscurity. Most of his papers, meanwhile, were transferred to Japan when his wife, the pianist Chieko Hara (1914-2001), returned to her country. After her death, her son donated them to the Museum of Education at Tamagawa University. As Hara and Cassadó left no apparent heir, his works remain in a limbo in terms of further access or the possibility of publications of his out-of-print works or unpublished work.

Over the past twenty years, however, Cassadó has been rediscovered by musicians and researchers, including Gabrielle Kaufman, a cellist and scholar in Barcelona, whose book Gaspar Cassadó came out in 2018 and includes the first complete listing of his more than fifty compositions. Meanwhile, he also features in a recent biography by Carmen Pérez Torrecillas of pianist Giulietta Gordigiani (1871-1955), the widow of Robert von Mendelssohn who was also Cassadó’s longtime accompanist and lover.

After Cassadó’s passing, his wife Chieko Hara founded an international cello competition in his name, which ended in 2013. Today, Cassadó’s cello compositions, Requiebros and his Solo Suite remain favorites in the repertoire of cellists around the world.

H. Rosi Song holds a Chair in Hispanic Studies at Durham University, where she specializes in 20th and 21st century Spanish culture and literature. Her most recent book, co-written with Anna Riera, is A Taste of Barcelona. The History of Catalan Cooking and Eating. She is currently engaged in a research impact grant from Durham University seeking to create a cultural and musical context from which Cassadó’s work can be discovered and studied in collaborations with professional musicians from the U.S., the UK and Europe.