Book Review: Black Soldiers in World War II

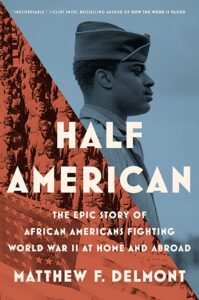

Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad. By Matthew F. Delmont. Viking, 2022, 374 pp.

Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad. By Matthew F. Delmont. Viking, 2022, 374 pp.

This new book about the role of African Americans during World War II has a rare and surprising opening on the subject: a full chapter titled “Black Americans Fighting Fascism in Spain”! Ever since Ernest Hemingway casually forecast in a journalist’s report that the Spanish Civil war was a “dress rehearsal” for a second world war, most writers, historians, and politicians have downplayed the idea that the conflict in Spain was a direct opening round in the battle against western fascism.

Yet Matthew F. Delmont, a historian at Dartmouth College, introduces the subject of Black participation in the anti-fascist struggle through the lens of the writer Langston Hughes, who journeyed to embattled Spain as a reporter for the Baltimore Afro-American. “If democracy is to be preserved in Europe,” Hughes wrote in 1938, “it must first be preserved in Spain. The world must rise to that issue or face an even greater offensive of the fascist powers.”

From that vantage point, Delmont follows the Hughes’ trail through his meeting with several African American volunteers in the XV International Brigade, including Thaddeus Battle, a Howard University student soldier who in turn introduced him to Bernard “Bunny” Rucker and other volunteers. He also interviewed nurse Salaria Kea. “These Negroes in Spain,” wrote Hughes, “were fighters—voluntary fighters—which is where history turned another page.” His proud affection for the Lincolns was reciprocated, and some of the poems he wrote in Spain appeared in the brigade’s newspaper, The Volunteer:

Just now I’m goin;

To take a Fascist town,

Fascists is Jim Crow peoples, honey—

And here we shoot ‘em down.

Delmont’s description is wholly supportive of the commitment made by US African Americans in Spain. But ironically, he seems to know little of the services that numerous black Lincoln veterans rendered during the big war that followed Spain—or even of the existence of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives and the ALBA collection at NYU, which clearly document their connection to the Second World War. To be sure, he does mention the posthumous military honors won by Sergeant Edward C. Carter, though he claims Carter spent two years in Spain, when the truth is that there is almost no documentary trace of his presence in the Spanish war. And while Delmont mentions that Paul Robeson’s name appears on an ambulance donated to the Spanish Republic, he does not seem to be aware of the fact that the great entertainer himself went to Spain to give political support to the cause, sang to the soldiers, and left a legacy of inspiration. Even Bunny Rucker, who gave Hughes a warm jacket and whose World War II letters were published by ALBA sixteen years ago, goes entirely unmentioned.

Nonetheless, the core focus of this book, as its title asserts, is on the heroic struggles of African Americans during the war against fascism. Delmont is astutely aware of the pervasive hypocrisy of white leaders and rank-and-file followers who consistently treated black soldiers and civilians with hatred and violence. Drawing on diverse sources, especially from the Black press, he depicts one evil situation after the next as well as the stubborn resistance of Blacks to institutional racism. Finally, he usefully follows the Black veterans of the US military into the civil rights movement and the desegregation of the army.

Although it’s a horrible story to confront, I recommend this book to every schoolteacher and anyone who denies that racism sleeps at the soul of our country.

Peter N. Carroll is co-editor with Michael Nash and Melvin Small of The Good Fight Continues: World War II Letters from the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (NYU Press, 2006).