Book Review: Kate Mangan’s Persistent Ingenuity

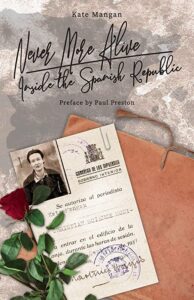

Kate Mangan, Never more alive: Inside the Spanish Republic. The Clapton Press, 2020. 346pp.

Kate Mangan, Never more alive: Inside the Spanish Republic. The Clapton Press, 2020. 346pp.

Kate Mangan, who claimed never to have been more alive than during the first year of the Spanish Civil War when she volunteered to help defend the Spanish Republic, was long a relatively unknown figure among the thousands of foreigners who traveled to Spain during the conflict. Strangely, for example, she is absent from Angela Jackson’s thoroughly researched British Women and the Spanish Civil War, although Jackson did consult the papers of Kate’s fellow volunteer Jan Kurzke—papers held by the daughter that Mangan had with him. It is this same daughter, Charlotte Kurzke, who has now edited her mother’s memoir.

Born in 1904 as Katharine Prideaux Foster, Mangan was an artist who studied at the Slade School of Art in University College, London, and also worked for a couturier as a mannequin. Among the many things we learn from this diary, published by the Clapton Press with a preface by Paul Preston, is the fact that it wasn’t exactly Mangan’s ideals or political convictions that took her to Spain.

In the early summer of 1936, Kate happens to find herself on vacation in Portugal with her new lover Jan Kurzke, a handsome German who has escaped the Nazis and fled to England. In Cascais and Estoril they run into the Spanish royal family, exiled there since the proclamation of the Republic in 1931. In mid-July, Jan and Kate’s idyllic vacation is interrupted by the rebellion of the fascist generals in Spain against the duly elected government. Jan is immediately possessed by the desire to go fight the fascists, and they return to England so he can arrange to become one of the first to join the International Brigades along with thousands of young men and women from all over the world. In other words, Kate Mangan initially went to Spain to follow her man.

At first, though, she is careful to hide this fact. The edition of her diary includes a letter from October 1936 addressed to the American writer Sherry Mangan, to whom Kate was still married at the time, in which she writes: “I would like to go to Spain and die too—all the people will die because they haven’t got any guns or airplanes.” She also claims she needs to rescue her niece, who is living in Barcelona with her Spanish husband. A few days later, she writes again: “…I went to Barcelona to fetch Tina and am now back in Paris with her. But I couldn’t resist the war atmosphere of excitement and alegría and am returning there tomorrow as I have joined up…” In practice, she comes across as much as a tourist of the war as a fighter and volunteer.

In a postscript, Jan and Kate’s daughter, Charlotte, tells us that after the death of her parents she found herself “in possession of two separate manuscripts of their memoirs.” Although she had understood that they were meant to be published together, she could not figure out how to make that work. Thanks to the Clapton Press, they have now both been edited, albeit separately. (Kurzke’s manuscript came out in 2021 as The Good Comrade.) Indeed, Mangan’s book is a testimony to filial devotion. Ms. Kurzke, for example, has taken trouble to identify all the characters her mother disguised with a variety of nicknames in her manuscript. She also provides the reader with excellent explanatory footnotes.

In his preface, Paul Preston calls Mangan’s “non-celebrity” memoir “one of the most valuable and, incidentally, purely enjoyable books about the war.” It stands out among the thirty thousand books about the war in Spain, he writes, for its “sheer wealth of fascinating information and insight provided in brutally honest and beautiful prose.”

More than anything, what comes to the fore in Mangan’s story is her persistence, resourcefulness, and ingenuity as a woman traveling in wartime Spain who finds herself on the outskirts of the political and ideological motives driving everyone around her. She makes it to Barcelona in spite of not obtaining a safe-conduct, and having her offers to transport medical or any other materials refused. She is unflappable and resilient throughout. In Barcelona she makes do with odd jobs translating or interpreting. She goes to Madrid, where she makes use of her command of several languages to get a job with the Spanish Government press office (her official ID is the image on the book’s cover). Even though she suspects that her lover Jan Kurzke does not want to be found (he never picked up the letters she wrote and left for him in Barcelona) she persists in tracking in him down, finding him in Malaga, where he lies wounded in a poorly appointed hospital. She also succeeds in getting him out of Spain and into Paris where he can receive better care for his shattered leg.

Still, Mangan’s story is surprisingly uneven. Although she writes well and many of her insights are quite perceptive, her depictions of other women are less than generous. Martha Gellhorn, who covered the war as a reporter, and Gerda Taro, the young photographer who died crushed by a tank, are not rendered kindly despite their important contributions.

In the end, though, readers’ take on this book will depend on what they want from a memoir about the war. The novelist Brigitte Giraud, in accepting this year’s Prix Goncourt, said that “the intimate only makes sense if it resonates with the collective, with a society, with a period, with a story.” My old friend M., who, like myself, grew up in Mexico as a Spanish refugee from the Civil War and has lived and raised a family in the United States for many years, told me that I should write down some of my family stories, because her historian son tells her that historians are always looking for such personal takes on historic events.

Paul Preston, a historian interested in such personal perspectives, admires the perceptiveness of Mangan’s profiles. But unless you have an affinity for “non-celebrity” memoirs, you may want to hold out on investing in this one.

Angela Giral, born less than a year before the start of the Spanish Civil War, grew up in Mexico as an exile and migrated to the US for graduate school at the University of Michigan. She practiced as a librarian in Princeton, Harvard and Columbia before retiring in 2004. After retirement she preserved and catalogued the archive of her grandfather, José Giral, a former Prime Minister of the Spanish Republic, now deposited in the Archivo Histórico Nacional in Madrid and available through PARES.