Why Does the Spanish Right Want to “Recover the Historical Memory” of Sephardic Jews?

Spanish conservatives who have rejected any accounting for Francoist crimes are nevertheless willing to make amends with the descendants of the Sephardic Jews who were expelled five centuries ago. The contradiction is only apparent.

“You have no historical memory, you don’t know anything about the past, and you cannot contribute anything to the future,” the conservative Spanish minister of Justice, Alberto Ruiz Gallardón, told Cayo Lara, leader of the leftist Izquierda Unida, in September 2013, after a heated exchange in the Spanish parliament over the 1977 amnesty law. Lara had argued for the revocation of the law; Gallardón against. To score his point, Gallardón quoted the legendary Communist politician and union leader Marcelino Camacho, who in 1977 had expressed his support for amnesty, which, he said, would “open the road to peace and liberty.”

The idea that building a democratic future requires the past to remain closed has been mobilized ever since to justify the silencing of Francoist repression. In fact, it is the main argument invoked by the Partido Popular (PP) to oppose the Law of Historical Memory, passed in 2007 under the then Socialist government. This law recognized the victims on both sides of the Spanish Civil War, gave rights to the victims of the dictatorship and their descendants, provided a path to Spanish citizenship for political exiles and their descendants, and formally condemned the Franco regime.

While critics to the left of the PSOE and the United Nations special rapporteur criticized the law for not going far enough, the PP voted against it, claiming that it served to weaken the political consensus of the transition to democracy and weaponized the Civil War for political propaganda. The PP and the far-right party Vox have since proposed an alternative “Law of Concord” to “close the wounds” of the past—and all further debate on the topic.

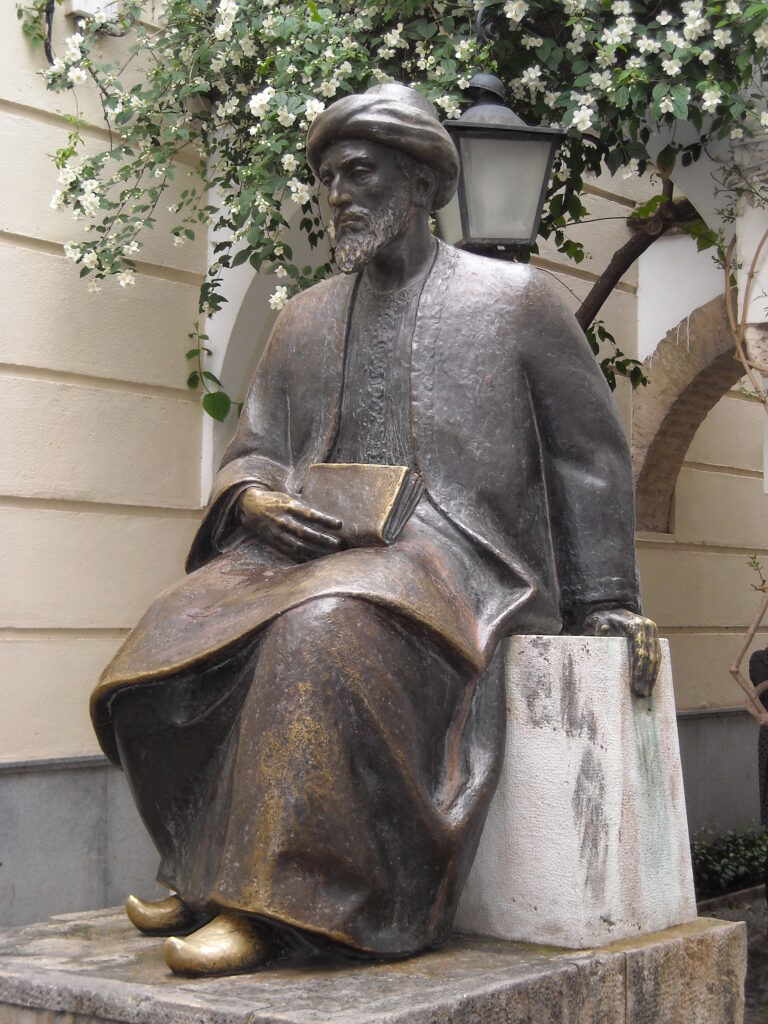

Strangely, the PP’s unwillingness to debate the victims of fascism has stood in sharp contrast to its position on revisiting Spain’s Jewish history. In fact it was Gallardón himself, as minister of Justice, who helped craft legislation (Law 12/2015) that granted an expedited path to Spanish citizenship to the descendants of Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula in 1492. The law’s preamble stressed “the shared determination to jointly build a new space of peaceful coexistence and unity in contrast to past intolerance.” The law, in other words, positioned democratic Spain as a nation looking critically at its intolerant past from a pluralistic vision of national identity.

When the law was approved in June 2015, Spanish officials and the leaders of the Federation of Jewish Communities of Spain emphasized its restorative function, celebrating “a new period of reencounter, dialogue and coexistence.” The Spanish law, much like a similar law passed in Portugal, expands “our understanding of reparation” as it offers “nonresidential dual citizenship with the goal of reconnecting a people wronged long ago to its roots,” Dalia Kadiyoti and Rina Benmayor argue in the introduction to their forthcoming book Reparative Citizenship for Sephardi Descendants.

In 2021, we had the chance to interview Gallardón. The law, he said, was meant to “ask the descendants of those affected for forgiveness” and to send “a message to the new generations that there are things that should never be repeated.” He also stressed how important it was that all political parties supported the law—an ironic position in light of his party’s steadfast opposition to the law of Historical Memory. In fact, he framed his law as “recovery of historical memory,” invoking the phrase championed by the Spanish memory movement in its demands for full accountability for Francoist crimes.

In other words, while the idea of reparations for Francoist repression, including amending the amnesty law of 1977, remains taboo among the Spanish Right, apparently it is acceptable to publicly address the memory of Jewish persecution and expulsion, albeit cursorily. In fact, it was the PP that took the initiative. How do we explain this paradox? What is it about the memory of the expelled Sephardi descendants that makes it acceptable to the Spanish Right?

Here it is important to remember that in earlier periods, particularly during the Franco era, Jewish leaders in Spain were pressured to lend legitimacy to particular government actions. Franco government officials believed in the existence of a “US Jewish lobby” influencing international public opinion. Accordingly, they viewed any “gesture of goodwill” toward Spain’s Jews as potentially helping Spain’s relations with the United States, which in turn proved crucial to overcome the regime’s international isolation after 1953. Some of these older assumptions—and relations between the Spanish Right and Jewish representatives—are still at play today. They were also implicit in the creation of Law 12/2015. “The Jews represent a convenient memory,” Holocaust scholar Alejandro Baer told us in 2021. “They don’t seek any revenge … They don’t challenge you and allow you to bolster the idea that there are others who should be forgotten.”

Thus, we witness a situation in which the historical memory of the Sephardic Jews—painted as a community that has maintained its love and loyalty for Spain despite persecution and expulsion, and that should be repaired for past wrongs—serves to delegitimize and undermine the historical memory of the victims of Francoist repression, along with the claims for historical reparation made by other minoritized groups over the course of Spanish history.

The truth is that the law for Sephardi descendants pays little more than lip service to a democratic, tolerant, or multicultural vision of Spain. In practice, Spanish citizenship remains a privilege difficult to attain, as applicants are asked to meet a series of specific expectations and bureaucratic requirements. In the end, the Spanish Right’s wholesale rejection of the Law of Historical Memory regarding the Spanish Civil War and its reparative gestures towards the memory of Sephardi descendants spring from the same source: a vision of nationhood built on a limited notion of “concordia” that does not truly examine the past but uses it to further cement conservative notions of unity and Spanishness.

Daniela Flesler is Professor in the Department of Hispanic Languages and Literature at Stony Brook University. Michal Friedman is the The Jack Buncher Endowed Chair in Jewish Studies at Carnegie Mellon University. This essay is based on research for their chapter “Negotiating Historical Redress: The Spanish Law of Nationality for Sephardi Descendants and Spain’s Jewish Communities,” in Reparative Citizenship for Sephardi Descendants: Returning to the Jewish Past in Spain and Portugal, ed. Rina Benmayor & Dalia Kandiyoti, forthcoming with Berghahn in 2023.