Scholars Launch Online Museum of the Spanish Civil War

More than 120 objects displayed in five galleries, with each object accompanied by a 350- to 500-word mini-essay available in both English and Spanish: The new Virtual Museum of the Spanish Civil War is in its first phase but already has a lot to offer to a curious visitor.

More than 120 objects displayed in five galleries, with each object accompanied by a 350- to 500-word mini-essay available in both English and Spanish: The new Virtual Museum of the Spanish Civil War is in its first phase but already has a lot to offer to a curious visitor.

The result of eight years of work by an interdisciplinary team of seven experts based in Canada, Spain, the United States, and the United Kingdom, the online project (available at www.vscw.ca) aims to provide a global audience with an accessible, reliable, and free source of information and reflection on the many dimensions of the Spanish conflict.

Launched in the fall of 2022, around the time the Spanish Senate approved the new Law of Democratic Memory, the project immediately drew attention of the Spanish and international media, with articles in El País and The Guardian. In late October, I spoke with three team members: Adrian Shubert (York University, Canada), Andrea Davis (Arkansas State University, US), and Alison Ribeiro de Menezes (University of Warwick, UK).

Your first phase includes 123 objects divided over five galleries [sidebar]. What’s next? And, perhaps more importantly, what will the museum look like when it’s done?

Adrian Shubert (AS): Honestly, I don’t know if we can answer that question. This is an ongoing project. We’ve already started to work on new galleries, but we’ll also be adding objects to the existing galleries. In theory, the sky is the limit. Since this is not a brick-and-mortar museum, we are not bound by physical space limitations. Plus, an online museum is surprisingly inexpensive to maintain. In the end, we are only bound by our and other people’s willingness to devote time to it.

Andrea Davis (AD): In terms of next steps, what I am most excited about is our plan to create what we call an “open gallery.” The idea is to invite diverse audiences to help build the next phases of the project, so that this can become a living museum in which people from Spain and elsewhere get to contribute, and talk about, their own objects. We want to find ways to include students and other scholars as contributors as well. For me, it’s thrilling to think about building the mechanisms to allow for that kind of participation.

Alison Ribeiro de Menezes (ARM): We think it’s important to convey the idea that memory is a process, an ongoing dialogue. In that sense, it helps to include objects in the museum that can serve to spark a debate or discussion. Once people can begin uploading their own items, and explain why they matter, we’ll start to get a different sense of the texture of what people regard as being their or their family’s memory of the war. So far, most of our objects are loans from institutions—with all the copyright complications that come with that, though many institutions have been quite generous. Engaging the public more actively will no doubt spark its own set of questions about curation. It will be a challenge all of its own, but a tremendously exciting one.

Who is your intended audience? I noticed that the museum does not currently include a broad introduction to the war: the viewer is invited to dive straight into any of the modules. Additionally, given that the texts of the modules are the same in both languages, it seems you’re not assuming that English- and Spanish-speakers may arrive to the site with different levels of previous knowledge.

AS: That’s an interesting point. To be honest, with regard to the text we didn’t really discuss alternatives. What I can say is that we aim to reach the broadest possible public. In terms of language, one of our goals is to make the entire museum available in Catalan, Basque, and Galician as well, covering all of Spain’s co-official languages. It’d be nice to have it in French, too, but that’s a lesser priority.

AD: It’s true that the site does not provide one single path for visitors to follow. But that is exactly attraction of a digital project like this one. Every visitor can chart their own path. And we are working on features that will build even more ways of access. Already, for example, visitors can click on the metadata associated with the objects to see other objects from the same geographical area or the same lending institution.

Speaking of accessibility, have you considered adding some kind of reference feature, like a glossary, that will allow visitors to look up items or names they may not be familiar with?

AD: We have discussed creating a kind of thematic thesaurus, yes. The challenge is to do that while maintaining the integrity of the gallery approach.

ARM: We’d also like to introduce links for visitors who want to dig deeper into a particular topic or object—or students, say, who wish to undertake a research project. We want to encourage the audience to think, inquire, and investigate on their own, engaging more deeply with the subject matter.

Your launch coincided with the adoption of Spain’s new Law of Democratic Memory, which, as we know, has been quite controversial. A coincidence?

ARM: Yes, it’s a coincidence, but I would say it’s a felicitous one. That said, our project is not linked to any kind of government policy. Ours is an academic effort aimed at public engagement. We’re also hesitant to call our project “democratic” simply because it’s online. Digital poverty is real: not everyone has equal access to the internet.

The format you’ve chosen—explaining the war through meaningful objects and short, accessibly written texts—has forced you to strike a difficult balance between completeness and concision. At the same time, it seems you’re also trying to strike a balance between the authoritative voice of the seasoned investigator who confidently conveys the scholarly consensus, and a more open-ended approach that leaves room for debate and interpretation, for indeterminacy and multiple viewpoints. How did that balance play out in the team? Did you have disagreements?

The format you’ve chosen—explaining the war through meaningful objects and short, accessibly written texts—has forced you to strike a difficult balance between completeness and concision. At the same time, it seems you’re also trying to strike a balance between the authoritative voice of the seasoned investigator who confidently conveys the scholarly consensus, and a more open-ended approach that leaves room for debate and interpretation, for indeterminacy and multiple viewpoints. How did that balance play out in the team? Did you have disagreements?

AD: In a way, this is many projects in one. We agreed on common guidelines, but beyond that everyone was left in charge of different galleries and objects. Each of us brought our own knowledge and voice to the table.

AS: It’s also important to point out that not all of us are historians. Alison does cultural studies, for example, while Alfredo González-Ruibal is an archaeologist. We are all coming from different places. But that’s something we embrace.

ARM: In addition to the interdisciplinarity, the scholarly dimension of this work also posed a challenge. For example, we debated the extent to which we should include statistics, like numbers of victims. That quickly lands you in a debate: one scholar says X, another says Y. There is only so far you can go in that direction: footnotes have no place in a museum like this. While each of us has approached our work from our own disciplines, we share a commitment to fairness and transparency, rather than to promote one particular kind of narrative about the war.

Given the controversial nature of the war in Spain and elsewhere, you must have received interesting reactions already.

AS: We’ve received a lot of positive feedback, as well as offers from individuals who have objects they’d like us to include in the museum, which is great. Perhaps surprisingly, there have only been two negative emails. One, written in all caps, asked: “¿QUIÉN OS PAGA?”—Who’s paying you? That one clearly came from the Spanish far right. I think they didn’t realize there has almost been no Spanish government money involved in this project. (Laughs.)

AD: Some other emails have really compelled us to think. One person wrote to us about one of the objects in the museum, a photograph loaned to us by a public archive. The person writing explained to us that, in fact, the picture had been taken by their grandfather. This brings up interesting questions about provenance and about the stories that are lost or silenced when objects become part of an official archive. But those are exactly the stories that we hope to highlight.

Some of the Spanish media coverage of your project underscored the ironic fact that Spain itself still does not have a proper national museum of the Civil War. What’s your view on that?

AS: Antonio Cazorla Sánchez, who is part of our team, has an interesting take on that question. Compared to other European countries, he says, Spain has a real shortage of history museums altogether—especially when it comes to the twentieth century. The absence of a Civil War Museum, in other words, is really a symptom of a larger issue.

ARM: As an Irish person, I don’t think it’s right for me to opine about what museums Spain should or should not have. That’s not what our project is about. We merely seek create a space for information and reflection, and for voices that may otherwise not be heard or articulated. We want to engage the audience. And in a way, reactions like the one we received about the photograph that Andrea mentioned earlier do exactly that. No doubt Spain will someday have a museum of the Civil War. The time may not be right yet. But who am I to make that determination? In my own country, Northern Ireland, we don’t have a Museum of the Troubles. And any time they try and put on an exhibition of the Troubles, it must balance both sides so equally that it isn’t particularly incisive or insightful. But that is done for a good reason: namely, to avoid destabilizing things. Personally, I’m happy to sacrifice the Museum of the Troubles if we have a peace process. Spain, too, has to decide its own process towards the consolidation of democracy and the confrontation with its history. Our project can provide a view that is informed, in part, by outside perspectives. But we cannot claim that this is the substitute for something that Spain hasn’t done. That would be incredibly arrogant.

The Virtual Museum of the Spanish Civil War can be accessed for free at www.vscw.ca. It has been produced by a team of seven experts: Adrian Shubert, historian at York University; Alfredo González-Ruibal, archaeologist at Spain’s public research council (CSIC); Alison Ribeiro de Menezes, professor of Hispanic Studies at the University of Warwick; Andrea Davis, historian at Arkansas State University; Antonio Cazorla Sánchez, historian at Trent University; Dwayne Collins, librarian at Trent University; and Joan Maria Thomàs, historian at the Universitat Rovira I Virgili.

The Virtual Museum of the Spanish Civil War can be accessed for free at www.vscw.ca. It has been produced by a team of seven experts: Adrian Shubert, historian at York University; Alfredo González-Ruibal, archaeologist at Spain’s public research council (CSIC); Alison Ribeiro de Menezes, professor of Hispanic Studies at the University of Warwick; Andrea Davis, historian at Arkansas State University; Antonio Cazorla Sánchez, historian at Trent University; Dwayne Collins, librarian at Trent University; and Joan Maria Thomàs, historian at the Universitat Rovira I Virgili.

Here is a sampling of the galleries and objects:

Outbreak of the War and Course of the Conflict (40 objects): Dragon Rapide airplane, Mutinous sailors on the Jaime I, Montaña barracks, Street fighting in Barcelona, the Badajoz bullring, Belchite

International Context (25 objects): Great Britain and Non-Intervention, Nazi Germany’s support for Franco, Irish volunteers for Franco, Salaria Kea, Soviet agents in Republican Spain, Media war, Republican exiles in France

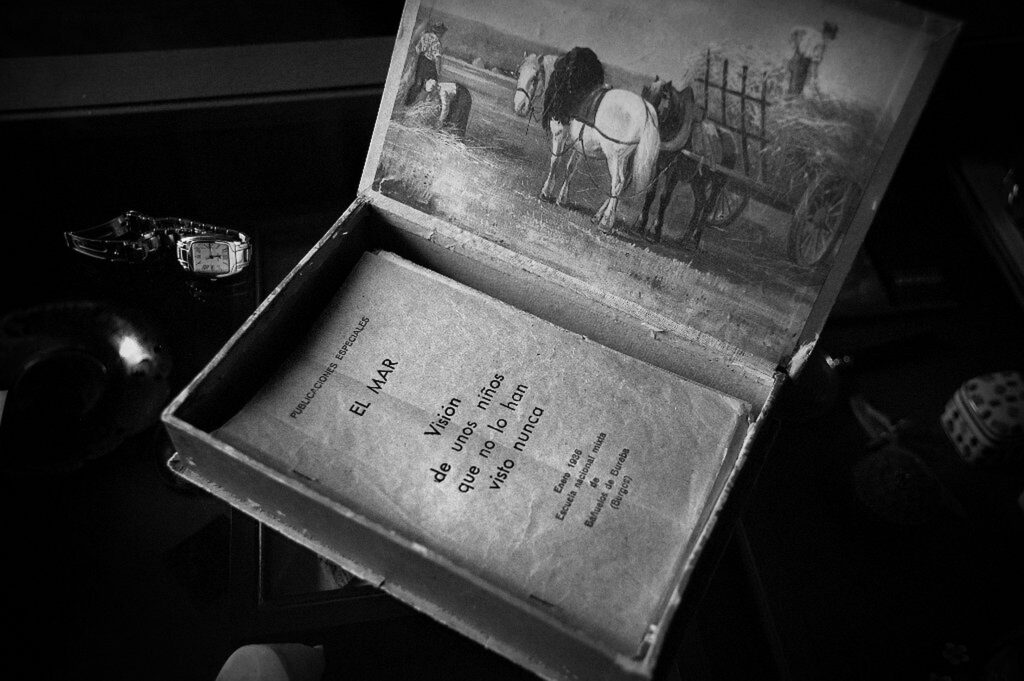

The Home Fronts (22 objects): The fate of a Republican school teacher, Paracuellos cemetery, Queipo de Llano’s microphone, A female officer in the Republican army

Daily Life at the Front (17 objects): Morphine ampoules, condom box, crucifixes

Historical Memory (19 objects): Valley of the Fallen, Statue of La Pasionaria, International Brigades Commemorative Plate, Renaming streets, Guernica