Gonzalo Berger: “Popular Culture Has Flattened the History of the Milicianas.”

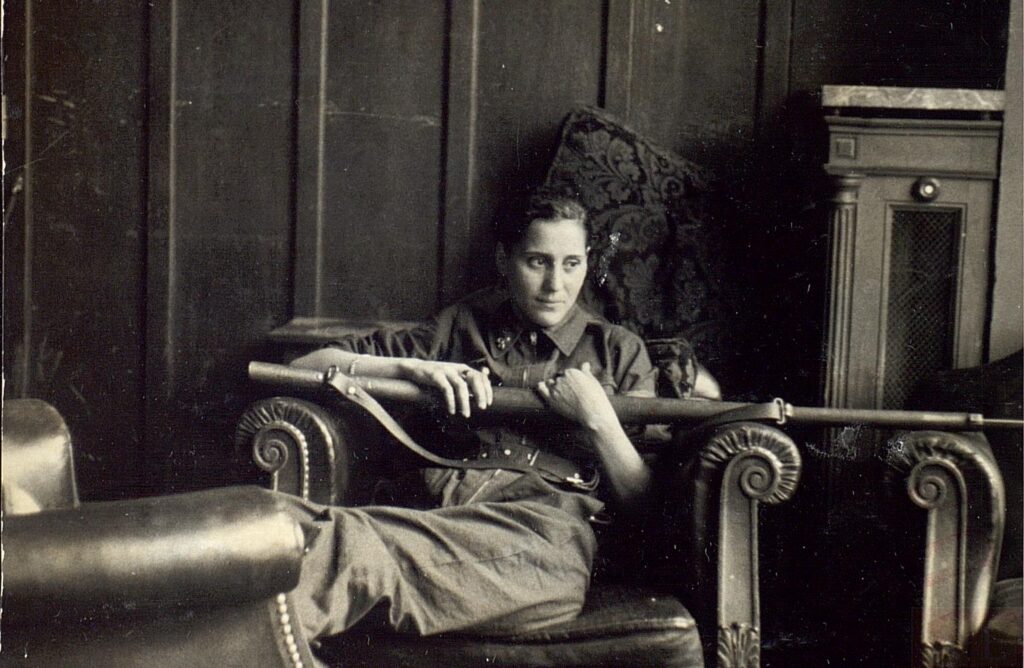

Miliciana at the Círculo de Bellas Artes, Madrid. Foto Remazán. CDMH FC-CAUSA_GENERAL,1547,Exp.1,N.594

The Catalan historian Gonzalo Berger, who’s spent years researching the participation of women in the antifascist militias and the Republican army during the Spanish Civil War, has just published a new book, Milicianas, that tells some of these women’s stories for a non-specialized audience.

This is not Berger’s first effort to bring the topic to the attention of the general public. In 2018, he collaborated on the documentary Milicianas, directed by Tània Balló and Jaime Miró; in 2021, he helped create the online Museum of the Woman Soldier (Museo Virtual de la Mujer Combatiente, www.mujeresenguerra.com).

The subtitle of your book suggests these women have been “forgotten.” How so?

The efforts to recover the memory of the Second Republic and the war has often focused more on men than on women. It’s true that the women soldiers have a certain place in public’s image of the war as well as in the historiography; books by scholars like Mary Nash and Lisa Lines have been important. Still, their stories are rarely touched in high school curricula. And even if these women do appear, they tend to do so in a very superficial and anecdotal way, either as heroines or the opposite, or merely as symbols in the Republican propaganda. In my view, they deserve better. More attention should be given to the actual roles they played in the war effort, their importance in terms of emancipation and equal rights, but also to the contradictions and complexities that emerge when one studies them as autonomous, politically engaged individuals.

Would you say that contemporary feminism has also forgotten about these pioneers?

Not at all. What is true, though, is that contemporary feminists have tended, in some cases, to paint them too simply in a heroic light, erasing their evolution and contradictions. What makes these women interesting, moreover, is not so much their individual stories as their collective impact on the society of their time and subsequent generations.

The image of the militiawoman has fascinated Spanish writers and film directors for years. I’m thinking, for example, of Vicente Aranda’s 1995 film Libertarias.

The image of the militiawoman has fascinated Spanish writers and film directors for years. I’m thinking, for example, of Vicente Aranda’s 1995 film Libertarias.

The problem in films like these is that the women soldiers are often infantilized. Time and again, we hear that these were very young women who often followed their male partners or family members into the war. This angle severely undervalues these women’s level of political autonomy. Similarly, we often see the women portrayed as nurses or cooks—as if that was all they did, or as if those roles were any less important for the war effort. Finally, popular culture tends to flatten history by resorting to gender stereotypes. For example, we often see an exaggeration of women soldiers’ sexuality to the point where it’s suggested that most of them were prostitutes. This is especially true of Libertarias, which, frankly, has had a hugely negative impact on the general public’s view of the milicianas.

In our last issue, we interviewed Esther Gutiérrez Escoda, whose research questions the whole notion that women were “relegated” to the rearguard when the militias were integrated into the Popular Army of the Republic. What does your research show?

Esther’s work is very important, and her book will mark a turning point in the way we think about gender in the Spanish Civil War. My research certainly aligns with her key argument, which is that many women continued to serve in the Republican army throughout the entire war.

Your book is structured as compelling series of portraits and vignettes. Why did you choose that format?

Because I think it’s the most accessible to a nonspecialized audience. It’s true that this means I’ve had to sacrifice the more theoretical part of my work, including some statistics and the extensive bibliography I’ve used, but there’s plenty of room for that in my more scholarly articles on the topic.

You’ve already hinted at the importance of getting these stories into the high school curriculum. If you had the chance to convince a 16-year-old why she should want to know about this chapter of Spanish history, what would you tell her?

I’d tell her that these women make clear that no one has the right to tell her what her place in the world is—and that, if someone does try to do that, she has the right to reject that imposition, just like the women in my book did. It’s also an important chapter in our history because it shows to what extent a culture of violence and authoritarianism can lead to war and bloodshed, the worst experience a human being can have. These women, who lived precisely such an experience, should interest us because we can learn from them. It’s the least we can do to honor them.

The recent debates around the Law of Democratic Memory in Spain have shown how much the memory of the war is still divided among party lines. Is it possible for a self-identified right-wing person in Spain today to appreciate the legacy of the women who fought for the Republic?

Although you are right that memory is still partisan—which also explains why memory policies shift radically every time government power changes hands—I do think that it is possible for a conservative Spaniard to appreciate the value of these women’s lives and experiences. On the other hand, machista attitudes are not exclusive to the Right; they exist on the Left as well.

What has it been like from an emotional point of view to write about these women’s extraordinary lives?

The emotions have definitely been mixed. Although I’ve felt admiration, a certain melancholy is also unavoidable: after all, there is so much that could have been achieved and wasn’t, so many opportunities lost. It’s hard not to empathize with the defeat they suffered, as women and as antifascists. Those who survived were often forced to resign themselves to a world that was very different from the one they fought for.