Book Review: Women Veterans of the Spanish War

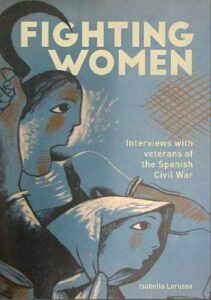

Isabella Lorusso, Fighting Women: Interviews with Veterans of the Spanish Civil War. London: Freedom Press, 2020. 185pp.

Isabella Lorusso, Fighting Women: Interviews with Veterans of the Spanish Civil War. London: Freedom Press, 2020. 185pp.

Isabella Lorusso’s Fighting Women: Interviews with Veterans of the Spanish Civil War, a translation of her 2019 book Mujeres en lucha, chronicles the experiences of eleven left-wing women involved in the body politic of 1930s Spain. An independent scholar of the Spanish Civil War, Lorusso interviewed anarchists, members of the POUM, a communist, and a Catalan feminist living in Barcelona, Madrid, Paris, and other locations in France in 1996, 1997, and 2010. Many of the women were Catalan by birth while others hailed from central Spain. They all participated in left-wing activities in Catalonia during the Second Republic in Spain and the subsequent civil war.

In the brief introduction and prologue, Lorusso identifies the “direct gendered vision” of the conversations she had with her subjects, which focus on “emotions enriched with historical memory.” She also recognizes the difficulty of doing interviews with individuals who are asked to remember their personal involvement in an extraordinary era six decades prior. The book, she writes, should encourage the reader to “try to honor these women who gave their lives for a dream of love and freedom.” The foreword by Beatriz Gimeno, a deputy for Podemos in the Spanish parliament, and the afterword by Elisabeth Donatello position the publication as a testament to the feminism and activism of the women interviewed.

In their interviews, the women paint a picture of a society during the Second Republic and the civil war that was both expectedly chaotic and surprisingly normal. In some cases, life proceeded as usual. There were public dances, love-matches, and marital vows. Some of the women were studying when the war began, while others were in the workplace. When female suffrage was granted during the Second Republic in 1933, some of the subjects rushed into politics and the traditional world adapted. Several of the women were introduced to politics by their fathers, complicating traditional patriarchal rules and gender relations. Manola Rodriguez, a communist from Madrid, for example, remembers that although she sat alongside her father at secret political meetings, “as a man he had his own contradictions: at home he was the master and we had to obey him.”

Pepita Carpena recounts her early political involvement in the Anarchist movement and her eventual move away from the CNT and towards feminism. At age 14, already employed as a tailor and influenced by the local presence of the CNT, Carpena joined the textile trade union. Her politicization began at a young age, but she argues that her militancy took time to take shape, first as a member of the Libertarian Youth and then as a member of the Anarchist Free Women (Mujeres Libres). From the beginning of her involvement, Carpena faced sexism and the “strong machismo” polluted her early experience with anarchism. Although she credits the CNT with encouraging women to follow their intellectual and political interests, she claims that “all men are the same” when it comes to the limits of their tolerance of women militants. Disappointed, she decided to “work only with women.” Carpena remained committed to anarchist beliefs through her participation in the Mujeres Libres, where she felt empowered and experienced a feminist awakening that was not possible among the male ranks of anarchists. Her radicalization in Mujeres Libres included support for gay rights.

Because Lorusso provides limited assessment of the interviews, it is not clear how her publication fits into existing historiography within Gender Studies or within the history of modern Spain. Despite gearing the conversations toward feminism, sexism, and patriarchy, Lorusso does not draw any conclusions, nor does she identify common themes across her interviews. “The words of the protagonists alone,” she writes, “provide a historical, human, and personal view of what was their—and hopefully even our—revolution.” Yet she leaves it up to the reader connect the dots.

Still, Lorusso’s book prompts important questions. Do the women’s memories reflect the latent sexism of radical left-wing political groups? For example, does Pepita’s description of the boys’ club that was the Libertarian Youth point to a false narrative of women’s emancipation promised by anarchism? Fighting Women is useful to explore the limitations of communism and anarchism and the shortcomings of the Second Republic, as her interviewees provide a trenchant critique of the left-wing’s unwillingness to dismantle patriarchy. Significant gender-based discrimination was clearly detrimental to their political mobilization. The women express disappointment in the left’s inability to include gender in its social revolution. Their stories, in other words, challenge the popular narrative of women’s political integration under the Spanish Republic.

Lorusso’s book also contributes to the history of feminism. Do these stories indicate a growing wave of feminism in the 1930s, and if so, what kind of feminism? Likewise, where might left-wing feminism in 1930s Spain fit in the larger history of the movement? Spain is often discounted as a participant in early twentieth-century European feminism in part due to the influence of the Catholic Church and the Franco dictatorship. The testimonies in Lorusso’s book challenge this interpretation, pointing instead to the presence of a strong feminist movement shaped by women’s direct political experience. Pepita Carpena, for example, attests to a radicalism born from feminism more than from anarchism.

Lorusso’s book should be read alongside important scholarly studies like those of Victoria Enders and Mary Nash, both of whom have effectively used oral history in their analyses of women and gender in Spain during the 1930s. While Fighting Women has merit, it would have been even more valuable if it had included a critical assessment of the memories of the women Lorusso interviewed.

Jessica Davidson is an Associate Professor of History at James Madison University whose work focuses on twentieth-century Spanish political, social, and women’s history, women in right-wing politics and in dictatorships.